A less innocent and slightly more expensive balancing act between pulp formulas and artistic ambition lies behind Robert Aldrich's independent production of Kiss Me Deadly (1955)which, as we have seen in chapter 1, was a crucial event for the French auteurists, signaling the end of Hollywood noir. On one level, Aldrich clearly designed this picture to capitalize on the extraordinary success of lowbrow novelist Mickey Spillane. In the years between 1948 and 1955, Spillane wrote seven of the ten best-selling books of all time and almost single-handedly established a mass readership for the American paperback industry. Despite his worldwide fame, however, Spillane was considered too vulgar and controversial for the major Hollywood producers, and films based on his work were made without A-picture stars or budgets. Meanwhile, intellectuals and cultural critics regularly attacked his private-eye hero, Mike Hammera misogynistic, racist, avenging proletarian who deals out brutal punishment to commie traitors and voluptuous dames. Hammer's frankly pornographic adventures involve many of the same formulas that Hammett and Chandler used, but they are devoid of any redeeming social content. Pure masculine fantasy, they resemble an archetypal film noir without the intervening control of the Breen Office or the artistic superego. Here, for example, is the famous conclusion to I, the Jury, which was probably inspired by the film adaptation of Double Indemnity:

Slowly, a sigh escaped her, making the hemispheres of her breasts quiver. She leaned forward to kiss me, her arms going out to encircle my neck.

The roar of the .45 shook the room. Charlotte staggered back a step. Her eyes were a symphony of incredulity, an unbelieving witness to truth. Slowly, she looked down at the ugly swelling in her naked belly where the bullet went in . . . "How c-could you?" she gasped.

I had only a moment before talking to a corpse, but I got it in.

"It was easy," I said.

The film version of Kiss Me Deadly has a similar atmosphere, although most writings on noir describe it as a critique of Spillane. No doubt it had to be critical or revisionist to a degree if it wanted to achieve acceptance among reviewers and mainstream exhibitors; but within the limits of movie censorship in 1955, it also tried to give Mike Hammer's fans a good deal of what they expected. "We kept faith with 60 million Mickey Spillane readers," Aldrich claimed in The New York Herald Tribune, where he defended the picture as a work of "action, violence, and suspense in good taste." Scriptwriter A. I. Bezzerides more or less agreed, although he later confessed to cynicism: "I wrote it fast, because I had contempt for it. It was automatic writing. Things were in the air at the time and I put them in." 21

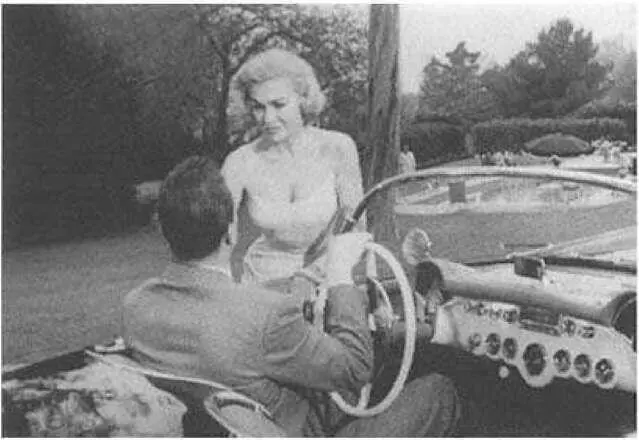

Bezzerides and Aldrich were in fact liberals, and for that reason, their film has a divided attitude toward the hero, who can be viewed as a conventional tough guy or as a kind of monster. Aldrich himself acknowledged this effect in a 1956 interview: "When I asked my American friends to tell me whether they felt my disgust for the whole mess, they said that between the fights and the kissing scenes they hadn't noticed anything of the sort." 22The adaptation nevertheless puts an ironic twist on the novel's politics, dispensing with Spillane's first-person narration and right-wing rhetoric and giving the women characters plenty of opportunity to criticize the phallic, self-absorbed private eye (despite the fact that they all find him sexually irresistible). Ralph Meeker, a method-style actor, plays Mike Hammer in Neanderthal fashion, and the film as a whole makes him seem vaguely repellent. A specialist in divorce cases and illegal investigations, he looks rather like a cross between Spillane's character and a Playboy male: thus he drives a foreign sports car, he employs a secretary who dresses in tights and does ballet exercises in his office, and he lives in a modernistic apartment with a fancy answering machine built into the wall. In keeping with this proto-Bond ambience, his sphere of operation has been changed from New York to Los Angeles, and he is sent in pursuit of a MacGuffin called "the great whatsit," which turns out to be an atomic bomb stolen by a criminal mastermind named Dr. Soberin. (The criminals in the novel are drug dealers; Aldrich and Bezzerides introduced the mad-scientist cliché because of censorship restrictions against drugs in movies.)

Throughout, Kiss Me Deadly alternates between social-realist scenes of urban decay and visions of a souped-up, hypermodern Americaa consumerist world of fast cars, pinup girls, monosyllabic tough guys, Bel Air swimming pools, Malibu beach houses, and nuclear fission. The pace and tone are perfectly described by Nick (Nick Dennis), Mike Hammer's auto-mechanic pal (and an alter-ego for scriptwriter Bezzerides), who keeps shouting "Va-va-voom!" In the end, as if to provide an ironic climax to all the explosiveness, Aldrich uses a device worthy of Dr. Strangelove (1964): Soberin's hideout at Malibu goes up in an atomic blast, wiping out both Hammer and the villains. (Some prints show Hammer and his secretary, Velda, escaping into the Pacific; their survival is doubtful, however, because they move only a few yards from ground zero.) The final, spectacular shots are brief but stunning, pushing the "lone wolf 1' myth of private-eye fiction to its self-destructive limit and reducing an entire genre to nuclear waste.

Even before the outrageous, apocalyptic ending, Aldrich and Bezzerides distance themselves from Spillane by filling the movie with signifiers of art, thereby establishing a counterpoint between the callous and the sensitive, the crude and the cultivated. For example, an important clue to the mystery is a couplet from Christina Rossetti's poem "Remember Me." ("But when the darkness and corruption leave / A vestige of the thoughts that once we had.") Elsewhere, the film contains allusions to Cerberus, Pandora, and the Medusa, along with fragments of music by Pyotr Ilich Tchaikovsky and Friedrich Flotow. (One of Mike Hammer's more brutal acts is to destroy a recording by Enrico Caruso; he himself listens to jazz singers like Nat Cole and Madi Comfort.) An even more obvious sign of the film's allegiance to critical modernism is its some-what commercially retrograde visual style. At a time when low-budget movies were increasingly turning to color and wide screens, Aldrich and cinematographer Ernest Laszlo remained faithful to Hollywood's semi-documentary, left-wing thrillers of the late 1940s: they used a grainy, black-and-white film stock that deglamorizes Hammer's world, and they photographed most of the action on location, mapping the shadowy decadence of Los Angeles from Malibu to Bunker Hill. They also borrowed considerably from Orson Welles. No Hollywood movie before Touch of Evil so skillfully explores the possibilities of wide-angle tracking shots and deep-focus compositions, and very few create a more jagged, out-of-kilter look. Like nearly all of Welles's best work, Kiss Me Deadly is an unusually dynamic and disorienting movieas in the weirdly reversed crawl that displays the opening credits, where Aldrich seems to be standing Mickey Spillane on his head. Throughout, the film's bizarre settings and wildly opposed cultural codes are set in conflict, and its soundtrack often becomes dissonant, almost hysterical. As a result, it provokes comparison with established forms of serious art. When Village Voice critic J. Hoberman reviewed the film for a New York retrospective in 1994, he praised its "crazy; clashing expressionism" and argued that "Hammer's quest is played out through a deranged Cubistic space amid the debris of Western civilization" (43).

Mike Hammer as Playboy male in Kiss Me Deadly (1955).

Читать дальше