The most celebrated director of this sort of "supporting" cinema is Edgar G. Ulmerwho, had he not existed, would probably need to be invented. A true aesthete of the lower depths, Ulmer seems to have taken a pleasure out of blending the sophisticated and the tawdry. He was in fact among the most talented of the many distinguished European émigrés to Hollywood during the 1920s and 1930s. While in Germany, he was a designer for Max Reinhardt; an assistant for F. W. Murnau, Lang, and Ernst Lubitsch; a codirector with Robert Siodmak on Menschen am Sontag; and a self-described "art-obsessed" intellectual who felt an affinity with Bertolt Brecht and the Bauhaus. In America, however, he spent much of his time on Yiddish art films, two-bit westerns, instructional films for the Ford motor company, and exploitation movies with titles like Girls in Chains (1943). "I knew [L. B.] Mayer very well," he told Peter Bogdanovich, "and I prided myself that he could never hire me!'' 16At the peak of his career, he was dubbed "the Capra of PRC," which meant that he had his own crew and relative freedom at a sub-minor-league studio. His masterpiece, Detour (1945), is a genuinely cheap production, photographed in only six days, with a two-to-one shooting ratio, seven speaking parts, and a running time of a little over an hour. As far as I can determine, its only U.S. review was in Variety, which said that it was "okay as a supporting dualer" (23 January 1946). It is nevertheless contemporary with the first group of Hollywood movies that the French described as American noir, and it can stand comparison with any of them.

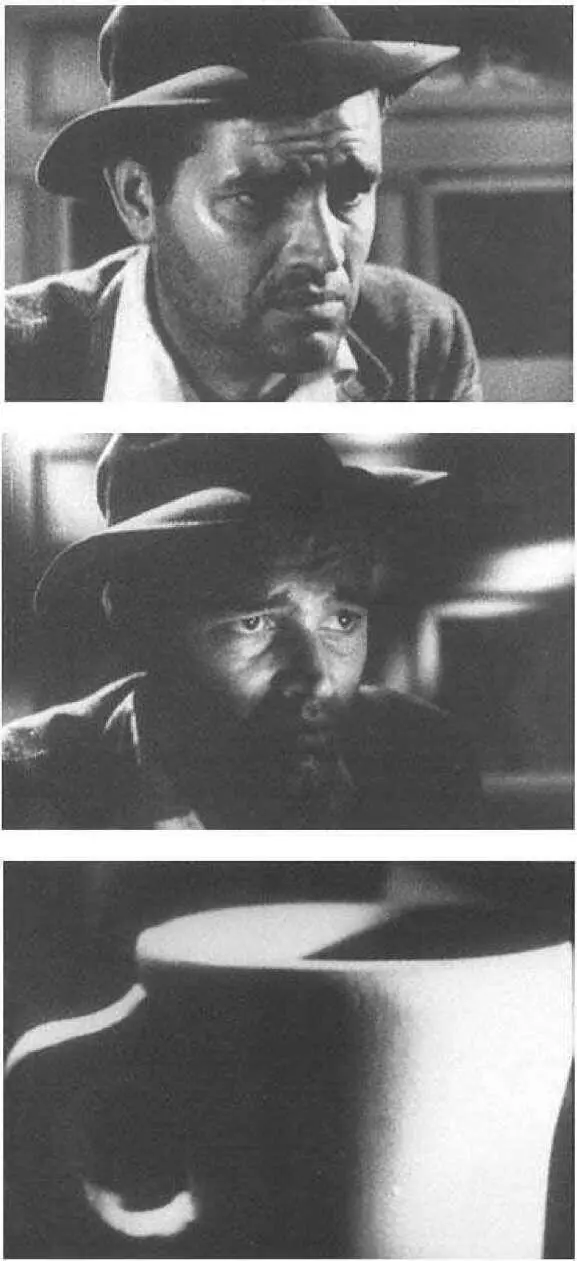

Detour's script, by Martin Goldsmith, is reminiscent of James M. Cain's novels (immediately after the success of Double Indemnity, Ulmer wrote a script for PRC entitled Single Indemnity), but it also borrows from the doom-laden, slightly crazed fiction of Cornell Woolrich and Frederic Brown, and from the uncanny, twist-of-fate stories that were common on radio during the 1940s. In keeping with these sources, its mise-en-scène is distilled from the essence of hard-boiled cliché. Near the beginning, we see the protagonist, Al Roberts (Tom Neal), wearing a rumpled suit, a snap-brim hat, and a five-o'clock shadow, drinking coffee in a roadside diner just outside Reno. When a truck driver drops a nickel into the jukebox, Roberts's offscreen voice asks, "Why was it always that rotten tune?" This leads to an obligatory flashback and to a bizarre tale of desire and death.

Like Walter Neff in Double Indemnity, Al blames his problems on destiny. The flashback begins by showing him in better days, playing a piano in a New York nightclub, where his girlfriend Sue (Claudia Drake) is the featured singer. Al seems to have talent, but when Sue moves to Los Angeles in hopes of becoming a star, he sinks into a black mood. At one point, working solo in the club, he performs a rather violent, boogie-woogie rendition of Brahms, for which he receives a meager tip. Soon afterward, he quits his job and hitchhikes westward. For all his travels, however, he goes nowhere. On the highway, he catches a ride in a flashy convertible driven by Charles Haskell (Edmund MacDonald), who exhibits an old dueling scar from his youth and a vicious scratch that he claims to have received quite recently from an angry woman. That night, while Al takes the wheel, Haskell falls asleep in the passenger seat and dies under mysterious circumstances. Al fears that the police will accuse him of murder, so he buries the dead man and momentarily assumes his identity. After crossing the border into California, he gives a lift to a provocative female hitchhiker named Vera (Ann Savage), who subsequently identifies herself as the woman who scratched Haskell's hand. Vera scoffs at the idea that Haskell's death could have been an accident, and she threatens to expose Al unless he sells the car and gives her half the money. When they arrive in Los Angeles, she accidentally learns that Haskell was the heir of a dying millionaire, and she insists that Al continue his masquerade. She and Al spend the night in rented rooms, drinking heavily and quarreling over her scheme to collect the inheritance. When he refuses to go along, she picks up the telephone and runs into the bedroom, locks the door, and threatens to call the police. Al grabs the lengthy telephone cord and pulls it hard, trying to snap it free from the connection. When he breaks the door open, he finds that the cord has become entangled around Vera's neck. As he stands over her dead body, a dissolve takes us back to the diner in Reno, where the story began.

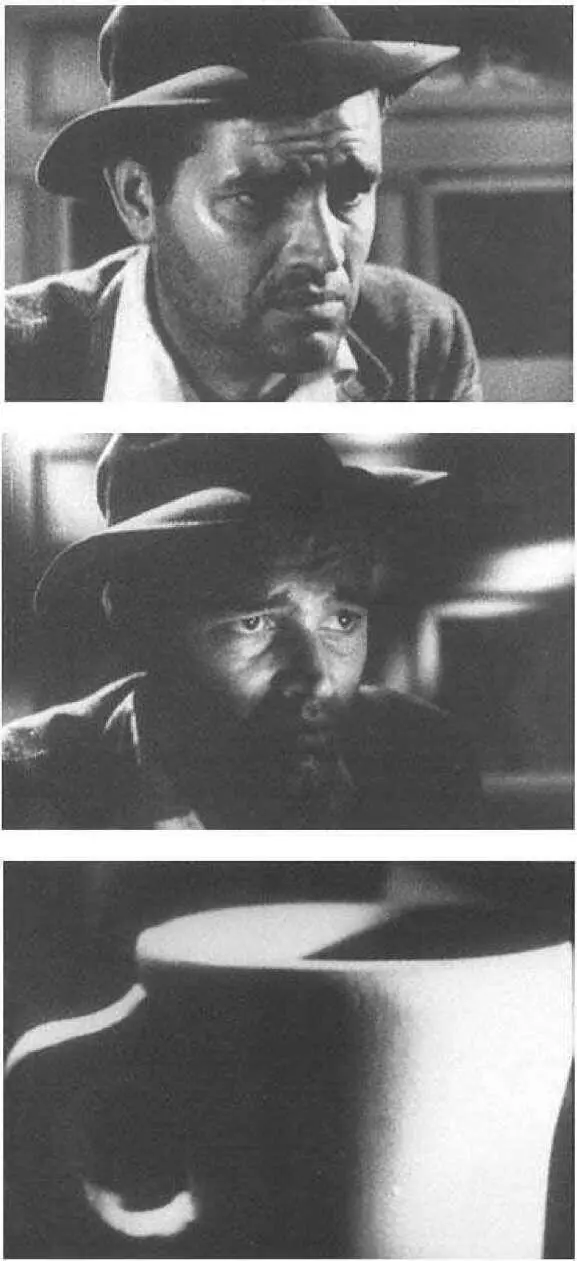

The haunted coffee cup in Detour (1945).

Detour is in many ways dated by its mode of production. The lush musical score by Leo Erdoty intensifies this quality, as do the cheap sets and the occasional technical flaws. But Ulmer is no Ed Wood. As only one example of his artistry, consider the early scene in the roadside diner, which involves a clever visual trick. As the jukebox plays "I Can't Believe That You're in Love with Me," Tom Neal is seen in medium shot from across the counter, a coffee cup near his right hand. The camera tracks forward to a tight close-up of his face, and the lights suddenly dim, signaling a transition into a subjective mood. A spotlight hovers around Neal's eyes, giving him a demonic look, and for a moment we can sense a technician behind the camera, trying to aim the light correctly. Neal broods, and the camera tilts down to view his coffee cup; what it sees, however, is a model, several times larger than the original, looming up before him in vaguely surreal fashion. (See figures 2527.)

Few people will notice that a substitution of coffee cups has occurred; indeed they are not supposed to notice, because Ulmer wants to create a dreamlike close-up of an apparently ordinary object and thus set the stage for the nightmarish flashback. In this regard as in others, he resembles Alfred Hitchcock, who once ordered his technicians to build a huge pair of women's eyeglasses for an important image in Strangers on a Train (1950). Not surprisingly, both directors were schooled in the German industry at a time when entire sets were constructed through the viewfinders of cameras. Ulmer had been Murnau's designer on Sunrise, one of the most artfully controlled films in history, and Detour is quite similar to that production in its studio-based expressionism, its careful attention to camera movement and offscreen space, and its intensely subjective narration.

Ulmer lacked the vast technical resources of Murnau or Hitchcock, but his relative poverty gave him certain advantages. Detour is so far down on the economic and cultural scale of things that it virtually escapes commodification, and it can be viewed as a kind of subversive or vanguard art. A radically stylized film, it is photographed almost entirely indoors, overcoming its severe budget limitations by means of process screens, sparsely decorated sets, and expressionistic designs. Ulmer represents his locales with a breathtaking minimalism: New York is nothing more than a foggy soundstage and a streetlamp, and Los Angeles a used-car lot and a drive-in restaurant. Meanwhile, he makes old-fashioned but highly effective use of optical devices such as wipes and irises, and he may be the only Hollywood director of the periodaside from Orson Wellesto deliberately exploit the artificiality of back projection. Notice the scene when Haskell falls asleep while Al is driving his car: behind Al, the white rails or fence posts on the side of the road become hugely magnified, flashing past in a hypnotic blur. 17

Detour also employs nearly all the modernist themes and motifs described in chapter 2.

Читать дальше