Souffle di riso carnaroli al limone Carnaroli rice and lemon soufflé

Tiramisu with banana and liquorice ice cream

Gelati e sorbetti Ice creams and sorbets

The science of ice cream

A note about the sugars

Sorbetto di melone Melon sorbet

Sorbetto di menta Mint sorbet

Sorbetto di basilico Basil sorbet

Gelato alla vaniglia Vanilla ice cream

Gelato al latte Milk ice cream

Gelato di crema Catalana Crème Catalan ice cream

Gelato al mascarpone Mascarpone ice cream

Gelato al timo limonato Lemon thyme ice cream

Gelato all’Amaretto Amaretto ice cream

Gelato al mirto Myrtle ice cream

Gelato al Limoncello Limoncello ice cream

Gelato al tartufo e miele Truffle honey ice cream

Gelato al caffè Coffee ice cream

Gelato alla liquirizia Liquorice ice cream

Gelato alle nocciole Hazelnut ice cream

Gelato al pistacchio Pistachio ice cream

Gelato al te Marco Polo tea ice cream

Gelato alla cannella Cinnamon ice cream

Gelato al panettone Panettone ice cream

Panettone

Amaretti biscuits

Almond tuiles

Hazelnut tuiles

Frangipane crisps

Hazelnut crisps

Mandorle, nocciole, noci e castagne Almonds, hazelnuts, walnuts and chestnuts

Special sablé biscuits

Salted special sablé biscuits

Biscotti al latte Milk crisps

Lemon thyme caramel crisps

Le guarnizioni Garnishes

Apple crisps

Candied mint

Candied vanilla pods

Cioccolato Chocolate

Chocolate parfait and foam

Torta al cioccolato e mandorle Chocolate and almond tart

Zuppa di cioccolato e yogurt White chocolate and yoghurt soup

Saffron and chocolate fondant

Chocolate fondant with Bicerin di Gianduiotto

Sformato d’arancia e cioccolato, pannacotta all’acqua di rose Orange and chocolate sformato sponge with rose water pannacotta

Frittelle di cioccolato e banana Chocolate and banana beignets

Formaggi Cheese

This life

Index

Photos

Acknowledgements

Also by Giorgio Locatelli

Copyright

About the Publisher

I wanted to call this book Made of Italy, because that is what I am – but I could as easily have called it La Convivialità – because that is the word I use most to explain the way Italians feel about food. For us the sign of welcome is to feed people. At the heart of all cooking, whether you are rich or poor, is the spirit of conviviality, the pleasure that comes from sharing a meal with others. And there is no enjoyment of food, without quality.

The way I think about food is entirely in tune with the Slow Food movement, started in Italy back in 1986 by Carlo Petrini in defiance of the opening of a McDonalds outlet in the Piazza di Spagna in Roma. Now a world wide force, Slow Food champions local, traditional produce with real flavour, made by caring people with skill and wisdom, which is celebrated every two years – with wonderful conviviality – at the Salone del Gusto, the famous food fair in Torino.

In the UK it is easy to blame supermarkets for clocking up air miles, for persuading us that we want fruit and vegetables that look perfect, but often have little flavour; for luring us on to diets of things that are salty, fatty, sugary and easy to eat; for packaging everything into convenient parcels so that we almost forget where our food comes from; and conditioning us to think that as long as our food is cheap, we are satisfied. But we have responsibilities too, and we have the power to change things. Of course I understand when you have kids you want to go to the supermarket, not traipse for miles trying to find a good butcher and fishmonger and green-grocer, and I’m not sitting here in my restaurant saying, you must do this and that, only remember that every time you pick up food in a supermarket, you are making a choice that has consequences. Where do you want to invest your money? In the profits of a supermarket, or in a farm rearing fantastic old breeds of pigs, or a small dairy making beautiful cheese?

You will see the letters DOP (PDO in the UK) and IGP (PGI in the UK) throughout the book. DOP represents Denominazione di Origine Protetta or Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), and it appears alongside the specific name of a product such as Parmigiano Reggiano or prosciutto di Parma. What it tells you is that in order to earn the stamp of the DOP and be allowed to use this name, the food must be produced in a designated area, using particular methods. IGP represents Indicazione Geografica Protetta, or Protected Geographical Indication (PGI), which is similar, but states that at least one stage of production must occur in the traditional region, and doesn’t place as much emphasis on the method of production. Whenever you buy Italian produce, look out for these symbols.

Salt should ideally be natural sea salt, and pepper freshly ground and black. Spend a little extra on good extra virgin olive oil and vinegar, and it will repay you a thousand times. And whenever possible buy whole chickens, and meat and fish on the bone, not portioned and wrapped in plastic.

All recipes serve 4, unless otherwise stated

‘You’ll never be a chef, Locatelli!’

‘Pass the prawns…the prawns…where are they…are they ready!’ I had been helping with the cooking in my uncle’s restaurant since I was five years old, but now, at sixteen, and a few months into my first real job, I used to get picked on all the time by the head chef. Now he wanted the prawns and they weren’t ready. The water in the pan was almost boiling. It needed to be boiling, before I put in the prawns, but I panicked and put them in anyway. He saw it and shouted at me, ‘You will never be a chef, Locatelli. You are an idiot,’ and he sent me to clean the French beans.

I couldn’t forget those words: ‘You will never be a chef.’ By the end of the day, I wanted to cry like a baby. I went home and my grandmother was waiting. ‘What does he know?’ she said. ‘Who is he?’ ‘He is The Chef!’ I told her. I would have run away, but as always my grandmother put everything into perspective, and she told me I had to go back and show him. So I went back. And I did show him.

My first feelings for cooking came from my grandmother, Vincenzina. But my first understanding of the relationship between food, sex, wine and the excitement of life came together for me very early on, when I was growing up in the village of Corgeno on the shores of Lake Comabbio in Lombardia in the North of Italy – long before I was suspended from cooking school for kissing girls on the college steps.

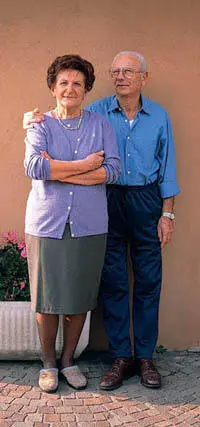

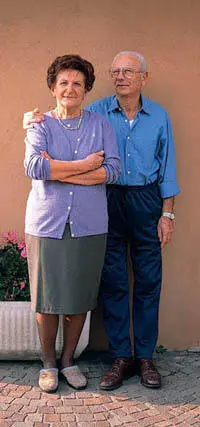

My uncle Alfio and my auntie Louisa, with the help of my granddad, built our hotel and restaurant, La Cinzianella – named after my cousin Cinzia – on the shores of the lake, on the edge of the village of Corgeno in 1963.

There were eight founding families in the village. The Caletti family, on my mother’s side, was one of them; and on my grandmother’s side, the Tamborini family, along with the Gnocchi family, who are our cousins, and who have a pastry shop in Gallarate, near Milano, in the hinterland, before the scenery changes from city to green and beautiful space, and where the speciality is gorgeous soft amaretti biscuits.

The shop gave me my first taste of an industrial kitchen. I used to love going in there as a kid, because the ovens were so big you could walk into them. In the season running up to Christmas, over and above the other confectionery, they would make around 10,000 panettone (our Italian Christmas cake). It was fascinating to watch the people take the panettone from the ovens, and then, while they were still warm, hang them upside down in rows on big ladders in the finishing room, so that the dough could stretch and take on that characteristic light, airy texture. Years later, when I first started in the kitchens at the Savoy, I felt at home immediately, because I recognized that same sense of busy, busy people, working away in total concentration.

Читать дальше