There was only one item Simon wanted: a photograph of his mother in old age.

There were paintings of her, when she was young and glorious. Simon wasn’t interested. He’d had nothing to do with her in those days. He doesn’t like portraits at the best of times, but he prefers at least that they correlate to an image already in his brain.

He held out his arms, eyes closed, to any other things the brothers didn’t take , then brought the fifty-or-sixty-item windfall back to a small flat he owns in London. There he laid them out, ten layers deep along one edge of the living room, like drying fish fillets.

Simon tells me he would like to hang the pictures up.

His mother has been dead nine years now, but the haul remains stacked against the wall, curing itself slowly of connotations. ‘Loveliness’ now resides only in the photograph of her old age and his memories.

The leftovers in his mother’s apartment – her letters, wrapped in pink ribbon, from a man who was not Simon’s father; her skirts and chemises, brooches, diamond pins, fur coats, perfumes, old swing-band records – the brothers sold, gave away or threw in the dustbin.

‘But you also got all your old school reports and exercise books, and the folder of newspaper clippings about when you won the Maths Olympiads and went to Cambridge, your IQ report?’

‘As I say, I didn’t want them.’

‘Then why take them?’

‘Why not take them?’

Simon is always eager to drop in schoolboyish retorts like this. The trick is to become instantly absurd.

‘Would you have taken them had they been roast chickens?’

‘Heh, heh, heh, hnnn. I took them because it’s the sort of thing people do take, isn’t it?’

See? Simple, when you know how.

To Simon, correct conduct is like a wood. It has many trees, which represent how things ought to be done; one tree for each circumstance. It is a large wood, sterile and rather dark. The stormy forest where he goes to hunt for the Monster is infinitely more comforting.

Here’s Simon’s brother!

Hello, Michael!

He doesn’t have much to say.

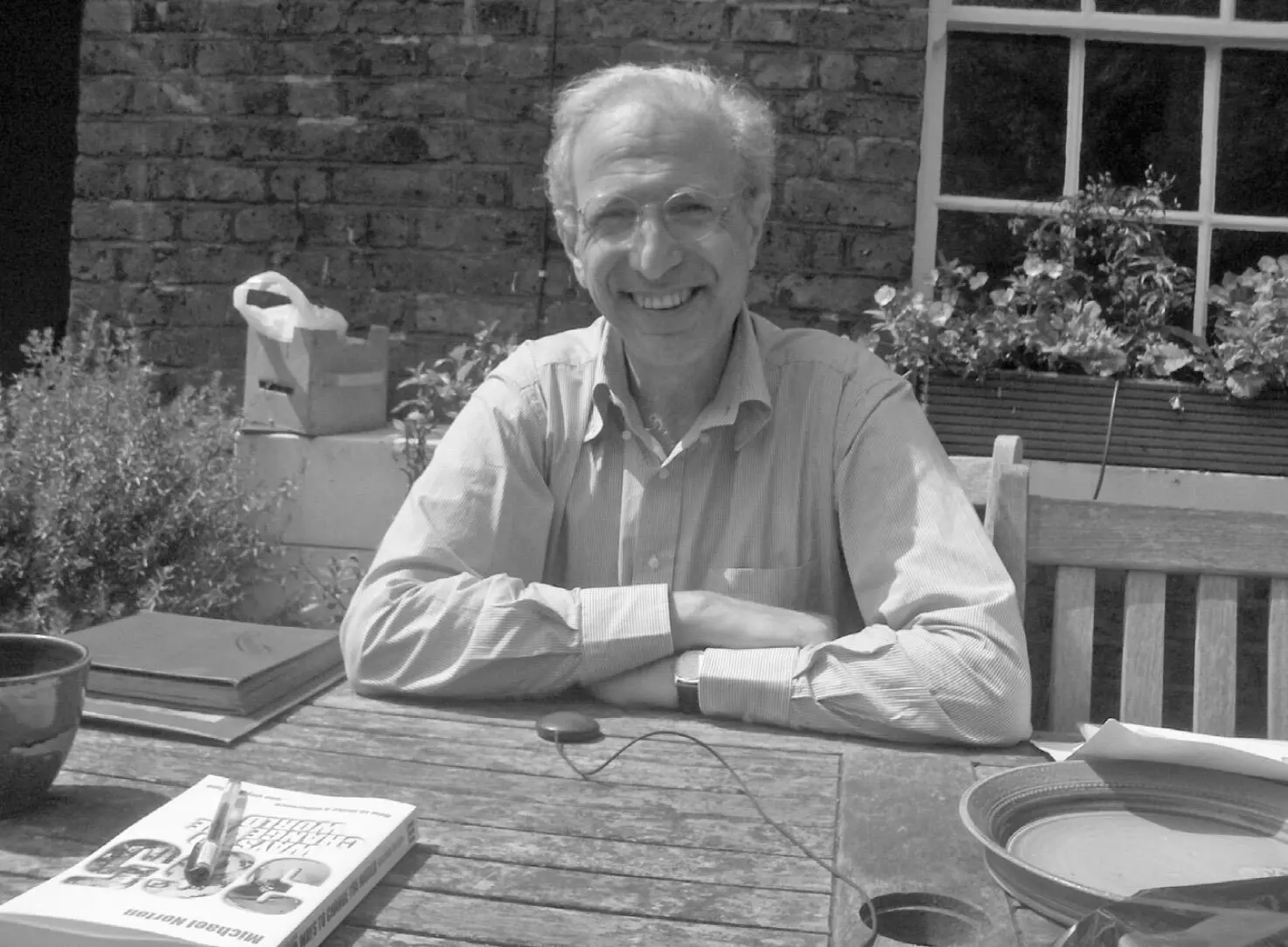

‘Is it surprising?’ he protests, leaping up, holding out his hand – a strong shake. ‘I’m ten years older than Simon is. We were like different families. I studied chemistry at university, not mathematics; that’s a different language. Simon is interested in chemistry also? Really? I never knew. His favourite element is Boron? I’m surprised! Would you like some tea? Organic Lapsang or elderflower?’

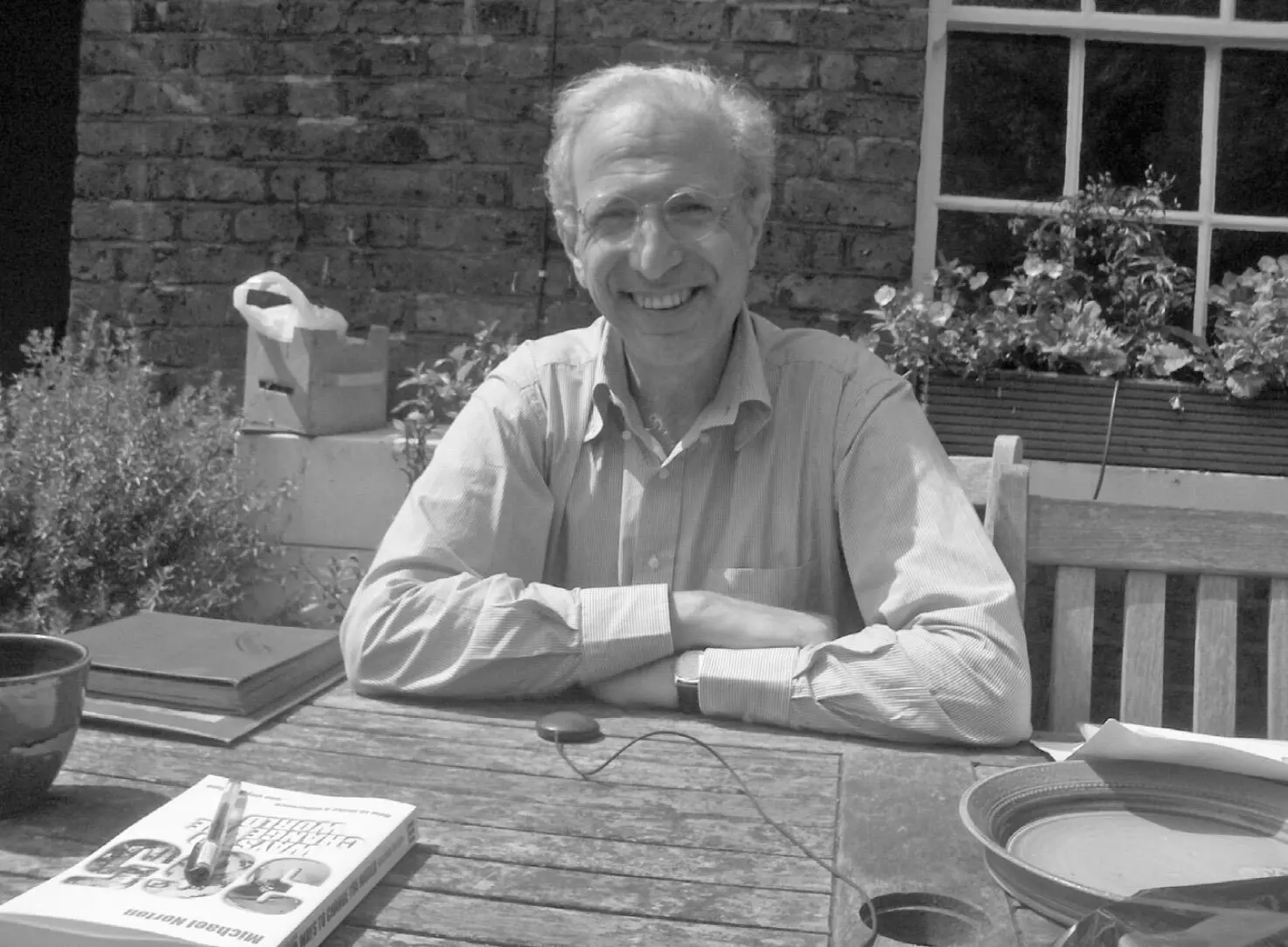

Michael Norton OBE is the author of Writing Better Fundraising Applications , The WorldWide Fundraiser’s Handbook , The Complete Fundraising Handbook and Getting Started in Fundraising . Money – in particular other people’s money – is a big subject in Michael’s life. He wants it to pay for environmental revolution.

His latest book is 365 Ways to Change the World: How to Make a Better World Every Day . Each day of the year is allocated a noble deed:

5 January : ‘Start drinking.’ Reduce ‘beer miles’ by giving up sewage brands like Heineken or Budweiser, and brew your own beer using oysters and wild rice.

22 February : ‘Say no to plastic bags.’ There are now 46,000 pieces of plastic waste in every square mile of the world’s oceans. In Australia, eighty million plastic bags are added every year to the mist of garbage that floats across the scrub there. Cows eat them and die; then the sack re-emerges from the rotting flesh, is cleaned off by rain, scooped back up by wind, and bundled along to be eaten by another cow: it is, biologically speaking, a protovirus. Simon is therefore a force for salvation. He keeps these viruses out of reach. If it weren’t for him, thousands of extra plastic bags from the Excavation would be tumbling through our fields and woodlands.

1 May : ‘Join the sex workers’ union.’ Fight to give prostitutes access to health care, safe places to work and legal support against rapists and pervy Italian prime ministers. ‘Membership is free.’

‘Michael Norton is a one-man “ideas factory”,’ bellows the Guardian .

‘You know, he knows when he comes to dinner here dressed in a dirty T-shirt that he’s doing wrong,’ says Michael, stooping under the lintel of his cottage door (he lives in Hampstead, but the house looks as if it’s been airlifted from beside a village brook in Hampshire) and balancing a tea tray. ‘But there’s no point telling him. You’d physically have to burn his old clothes before he’d get rid of them.’

He’s brought a photograph album into the garden along with the Victoria sponge cake. The album’s green, with a cushioned cover, from 1954, and it’s all the paperwork Michael has that includes Simon. They are not a sentimental family.

‘That’s my hand at the edge there, sorting out his food, even at that age. We’re at our summer bungalow in Ferring. This is David …’. David is a friend who later murdered his wife by bludgeoning her to death with a champagne bottle:

‘And here’s Simon aged … oh dear, not a pleasant-looking young man’:

‘Our mother doted on Simon. She was really proud that he was a genius. I don’t think she ever understood why he didn’t sustain that. I mean, he sustained it in his brain, but why is he not a professor? Why has he not got a proper job?’

‘He’s too peculiar,’ I suggest.

‘He’s not that peculiar,’ retorts Michael sharply, catching me out, correctly, in one of the phrases I have lately come to use about Simon without thinking. ‘There are lots of peculiar people in Cambridge. Half the dons that I had as a student there were peculiar. There must be somewhere that would give him a home.’

He taps his china cup of elderflower irritably.

‘All I can say is that since our mother died, Simon’s become a different person. I noticed that almost immediately. He’s got more sociable. When he comes to dinner, he’s much more at ease. Instead of sitting in a corner reading a book as he did when she was alive, he joins in. I’ve bought him three clean shirts which hang in a wardrobe here, for him to pick up whenever he comes to London.

‘I think my biggest triumph is persuading him to get rid of his money. Did you know, he gives £10,000 a year to campaign against cars?’

Francis Norton, Simon’s middle brother, works here …

… in a jewellery shop.

Francis brings in the family money. The company, founded by Simon’s great-grandfather, is the oldest family-run antique jewellery business in the world, patronised by the Queen, pop stars, fringe aristocracy, footballers (if they know what they’re about) and all London people with 100-acre second homes in Wiltshire.

Ten years before Simon was born, S.J. Phillips established itself as the epitome of Englishness by taking part in a famous wartime deception called Operation Mincemeat, later dramatised in the film The Man Who Never Was .

In April 1943, a Spanish fisherman discovered the decomposing corpse of a man floating off the coast of Andalusia. Documents on the body identified him as Major (Acting) William Martin of the Royal Marines. He was handcuffed to a briefcase, which contained a bunch of keys, an expired military pass, two passionate love letters, a picture of a woman in a swimming costume (‘Bill darling, don’t let them send you off into the blue the horrible way they do’), a £53 bill for an engagement ring and a letter from Lord Louis Mountbatten to General Alexander revealing the plans for the Allied invasion of Europe.

Читать дальше