ALEXANDER MASTERS

The Genius in my Basement

The biography of a happy man

Dedication

For gorgeous Flora

Oh dear, I have a feeling this book

is going to be a disaster for me.

Simon Norton

Contents

Cover

Title Page ALEXANDER MASTERS The Genius in my Basement The biography of a happy man

Dedication Dedication For gorgeous Flora

1

2 The reader meets Simon

Minus N

4

5

*6 The Monster

*7

45

9 eSimon

10 Mars

*11

12

*13

14

15

16 Simon Cuttlefish

*17

18

19

20 Eton

*21 3D chess

*22 Breakthrough

23 Breakdown!

24

*25 How to bag a Subgroup

26

*27 Garbage Bag Group

28

29 Great Silence

30

*31 The Monster

32 Atlas

33

34

*35 Moonshine

36 Discovery!

37

38

Acknowledgements

Further Reading

Also by Alexander Masters

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

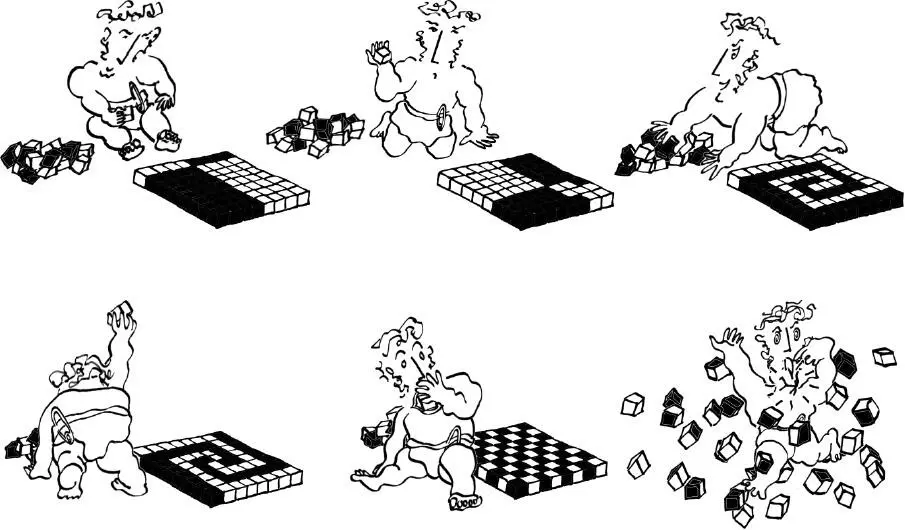

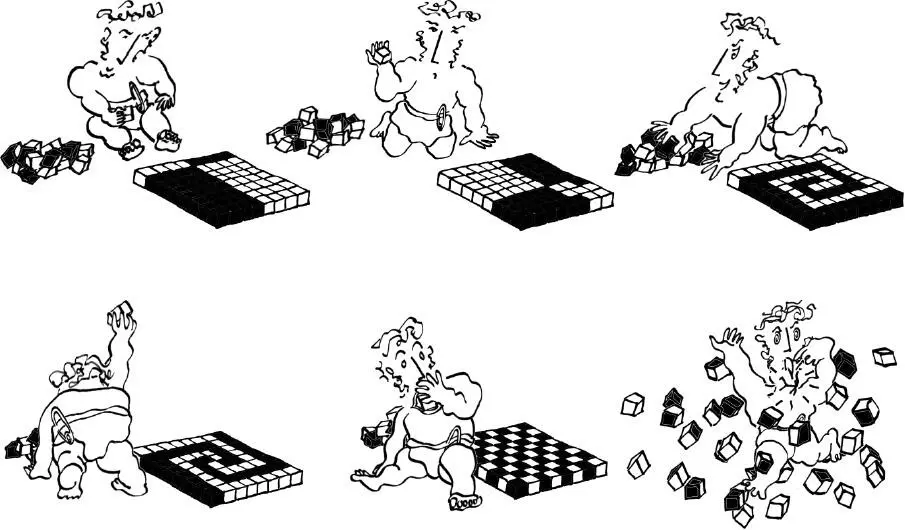

Simon was one year old, playing in the dining room, getting under his mother’s stilettos.

He was unusually thoughtful. His brothers at this age pounded the toy blocks on the glass coffee table and jabbed them into the electric sockets.

Simon picked up a pink block from the pile beside his knee and smoothed it against the carpet. Carefully, he positioned a blue brick alongside. He reached across – his mother, on her way to lay the side-plates and forks, had to make a sharp swerve – for two more pink bricks, and slid them against the blue. With precision, he extracted another blue brick.

Shuffling across the room on his bottom, Simon found four more pink bricks, fumbled them back and continued the arrangement.

His mother, halfway through folding napkins into bishops’ mitres, stopped in astonishment. She saw at last what he was doing.

One blue, one pink.

One blue, two pinks.

One blue, three pinks.

One blue, four pinks.

From the disarray of Nature, her baby son was enforcing regularity.

It took our species from the birth of prehistory to the dawn of Babylonian civilisation to learn mathematics.

Simon was bumping about its foothills in just over twelve months.

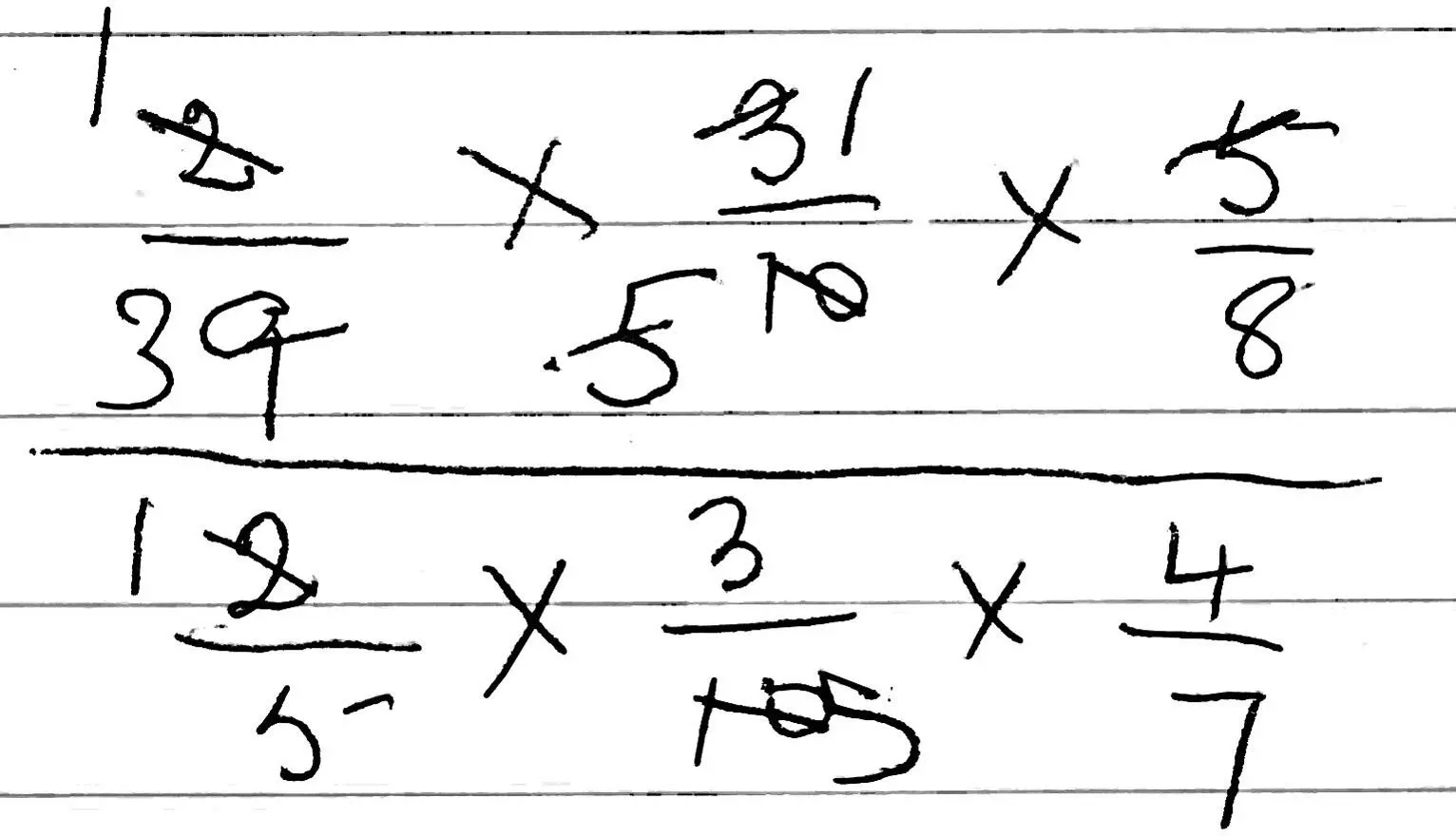

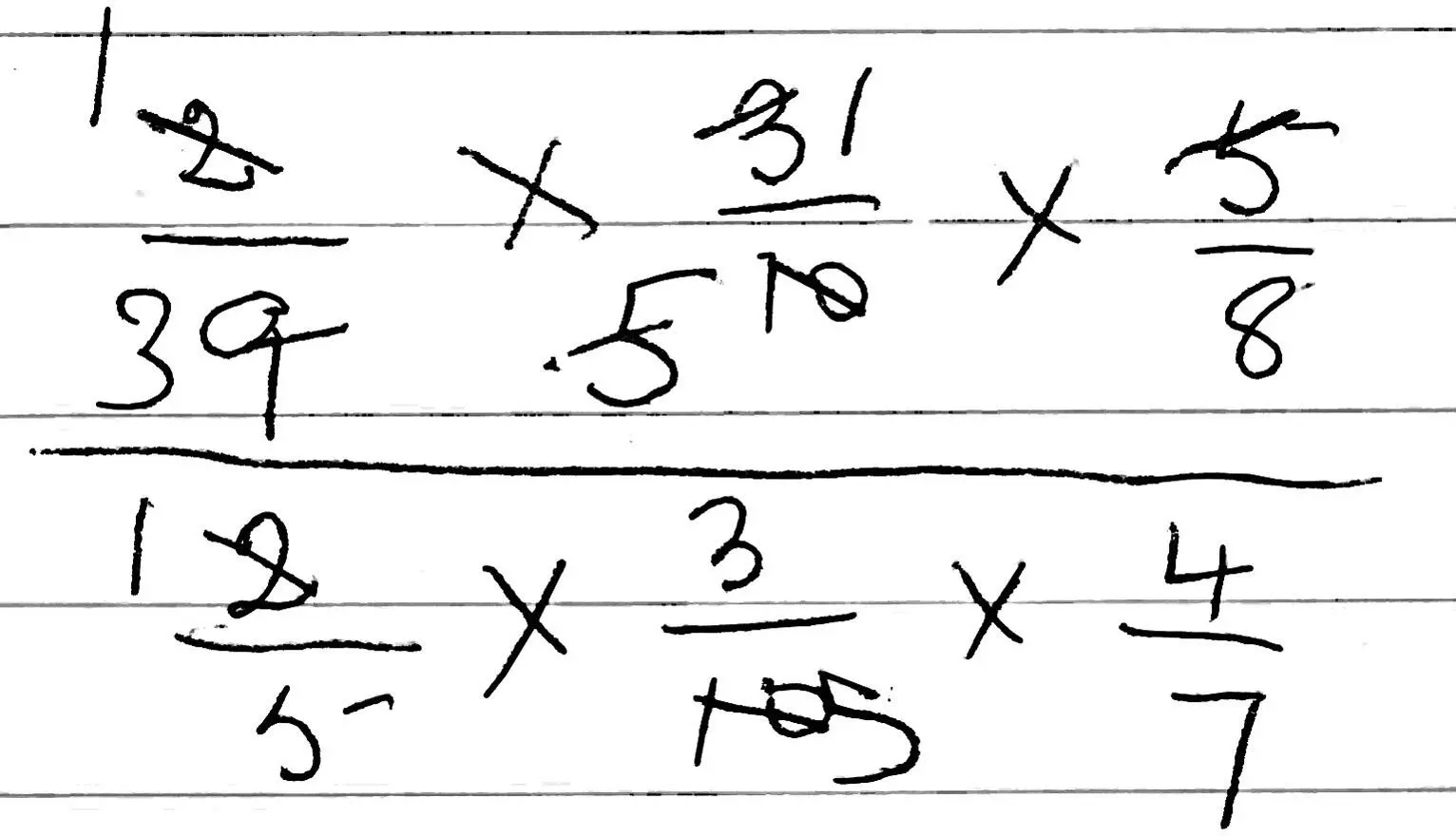

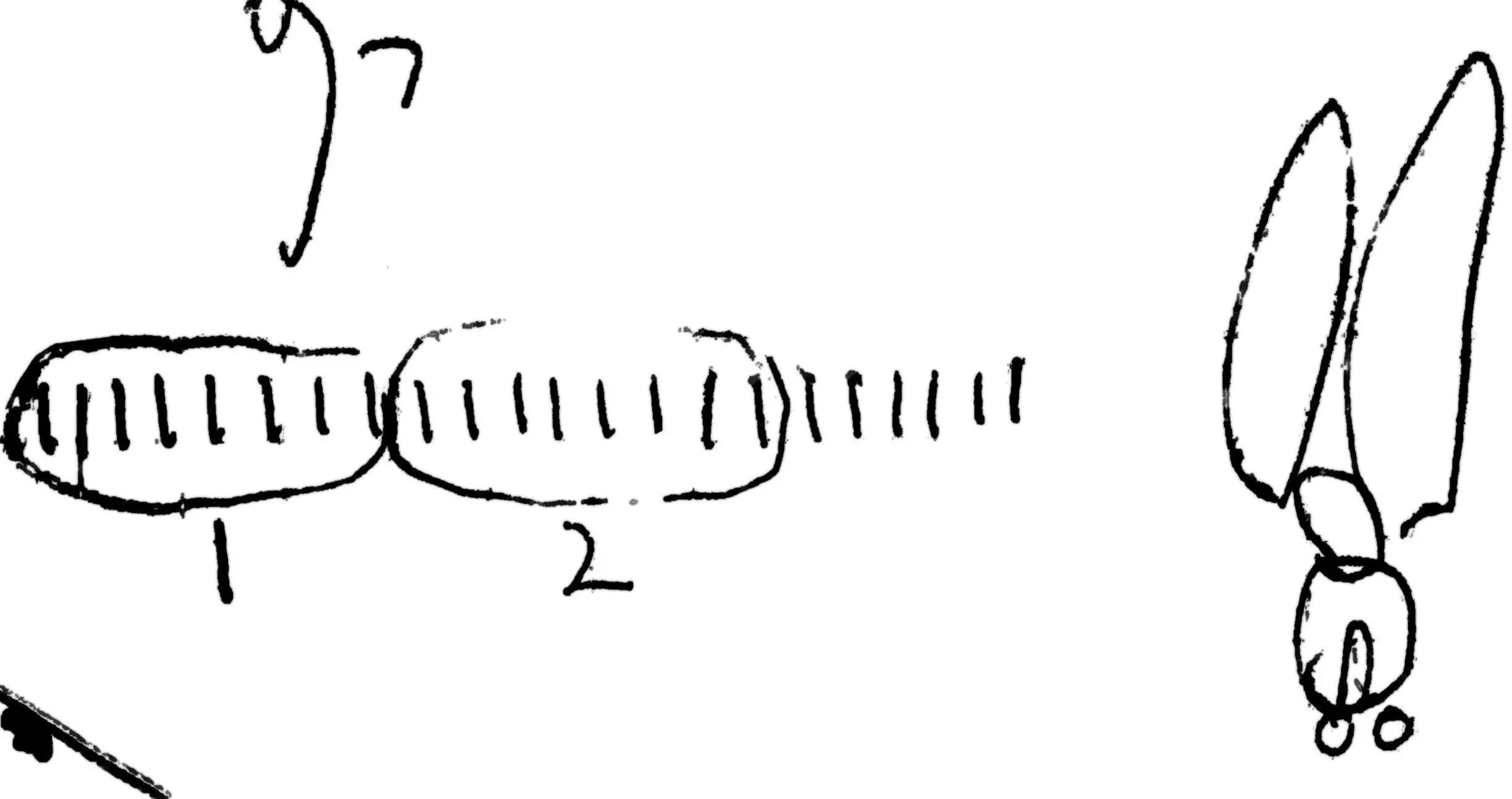

At three years, eleven months and twenty-six days, he toddled into cake-layers of long multiplication:

(January 1956)

Simon’s brother Francis had barely managed to recite the digits from one to ten by the time he was four years old; his brother Michael, a fraction quicker, had understood that if you gave him three banana-flavour milkshakes, and asked him to ‘count’ them, the correct answer was ‘one’ for the first, ‘two’ for the second and ‘three’ for the sticky splosh dribbling down his ear.

Percentages, square numbers, factors, long division, his 81 and 91 times tables, making numbers dance about to itchy tunes:

Simon mastered these when he was five.

Occasionally, his attention wandered:

2 The reader meets Simon

Sschliissh, dhuunk, dhuunk, zwaap, dhuunk, zwaap …

Listen! Can you hear?

… dhuunk, sschliissh, dhuunk, zaap, zwap, dhuunk … Bend down. Put your ear against the carpet: Zwaap, dhuunk, dhuunk, dhuunk,

zwaap, dhuunk, ssschliissh …

It’s fifty years later.

… liissh, dhuunk, dhuunk, dhuunk, zwaap, dhuunk, ssschliissh, dhunnk dhuunk, zwa ap, sclissh dhunnk, du unnk, sw

That’s the sound of a once-in-a-generation genius.

Simon Phillips Norton: Phillips, with an ‘s’, as if one Phillip were not enough to contain his brilliance. He lives under my floorboards.

Dhuunk, dhuunk …

When I first moved here, I had no idea what the noises were. Underground rivers? The next-door neighbours dragging a new pot through to their Tuscan garden? Dhuunk, dhuunk … But after eight years of interpretation I know that it’s the great man’s feet, stomping from one end of his room to the other. Every second stomp is heavier.

‘ Sssschlissh ’: that’s the swipe of his puffa ski-jacket against the stalagmites of paperbacks he keeps piled on the furniture.

‘ Zwaap ’: the sound of his holdall, as he rotates at the end of the room. He sometimes flings it wide, hitting papers. Simon carries this bag about with him everywhere he goes, clutched in the crook of his arm, even if it’s just to his front door to let in the gas man.

… dhuunk, dhuunk, dhuunk, zwaap, dhuunk, dhuunk …

Simon’s bed is ten feet directly beneath mine. My study is on top of his living room. His stomping space extends the full depth of the building, under my floor. My balcony is the roof of his basement extension, which has herded all the pretty garden plants into a six-foot square at the back of our house and stamped them under concrete slabs.

The phone rings. A charge from Simon: Dhuunk! Dhuunk! Dhuunk!

Snorting. The receiver – … rrinng , clank, clumpump, ping, ping … – wrenched from its holster. Attempts at speech, grunts, bangs of talk-noise; a strangulated word.

Clunk . Phone back in its holster.

Silence.

Dhuunk, dhuunk, dhuunk …

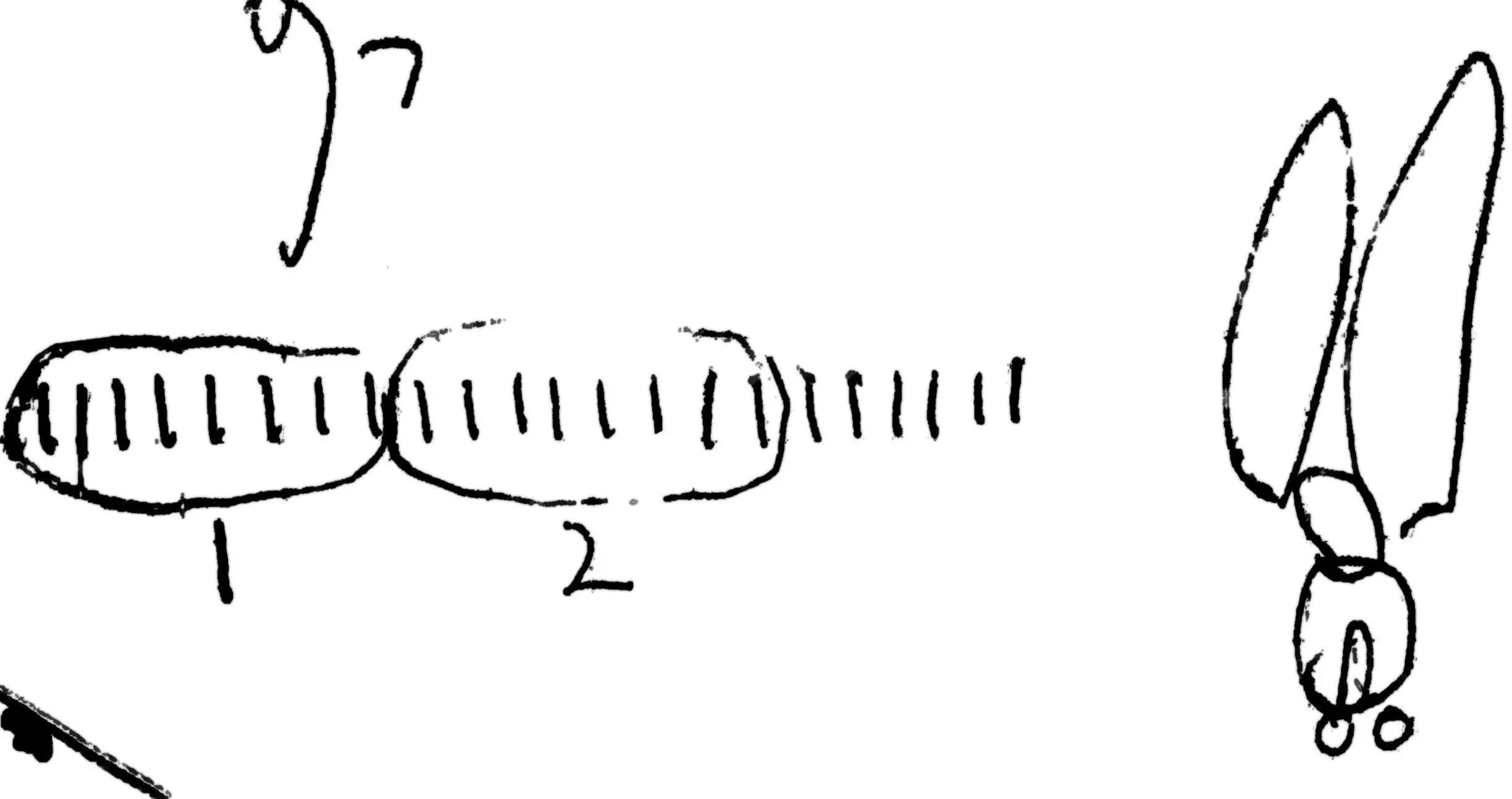

There’s another very important sound, which is too difficult to represent typographically: an intermittent, twisted crackle, sharp but thick, with a strong sense of command, resting on a base of plosive disorder. In an exercise book from when he was five there’s a squiggle that comes close:

It’s the sound of plastic-bag-being-opened-in-a-hurry-andthe-gratification-of-discovering-important-papers-inside. Without understanding this noise, you cannot understand the man.

… ssschliissh, dhuunk, zwaap, zwaap, dhuunk, dhuunk … Simon has been pacing down there for twenty-seven years, three months, five days, thirteen hours and eight minutes.

Ssssh!

Stop breathing!

Did you catch that?

Still another sort of noise?

A sort of sigh?

That was a thought.

Minus N

Your representation of me as interesting is

inaccurate. I feel ashamed by it.

Simon

Damn! He’s gone!

Simon’s refused to enter the book!

He is a Minus Norton. ‘Why now?’ I demanded, jumping up from the carpet when he stomped into my study from the basement. ‘The reader has started the story. He’s spent the money. He feels conned.’

‘How do you know it’s a he who’s reading it? It might be a she, hnnn.’

‘He or she! Who cares?’

‘I presume they do,’ he said cunningly.

Behind him, a bubble of air floated up the stairs and expanded into my rooms of the house, whiffing of damp and sardines.

Читать дальше