So, although it seems possible that:

3 + 2 = 5

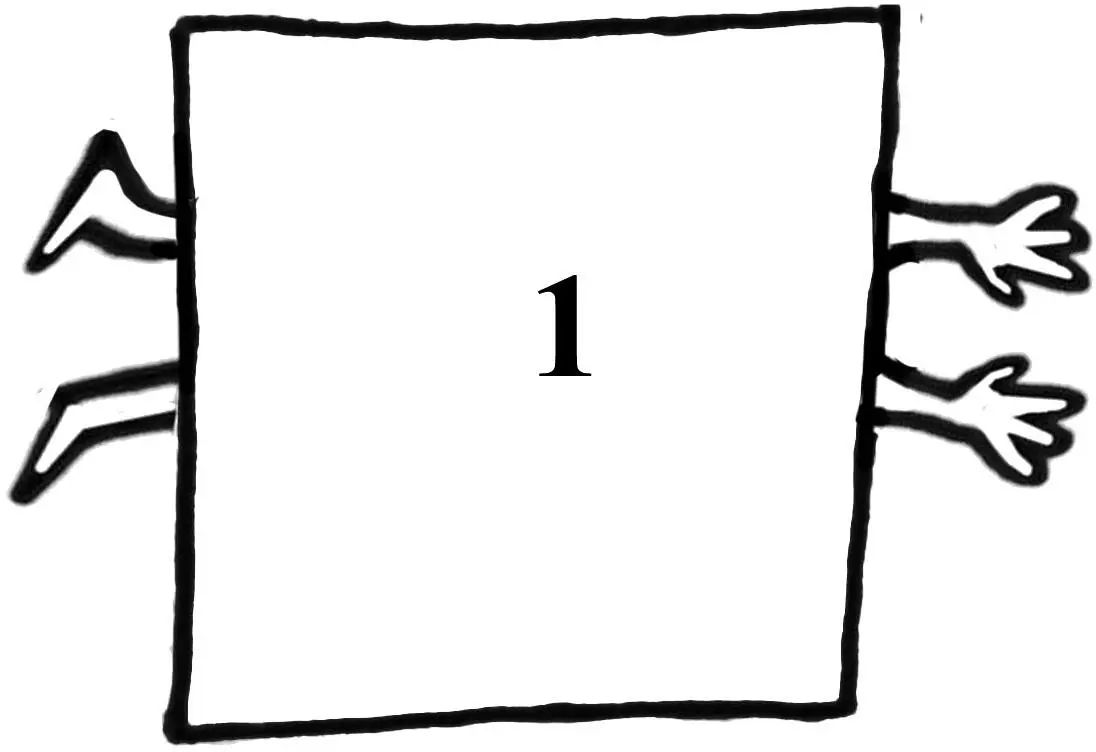

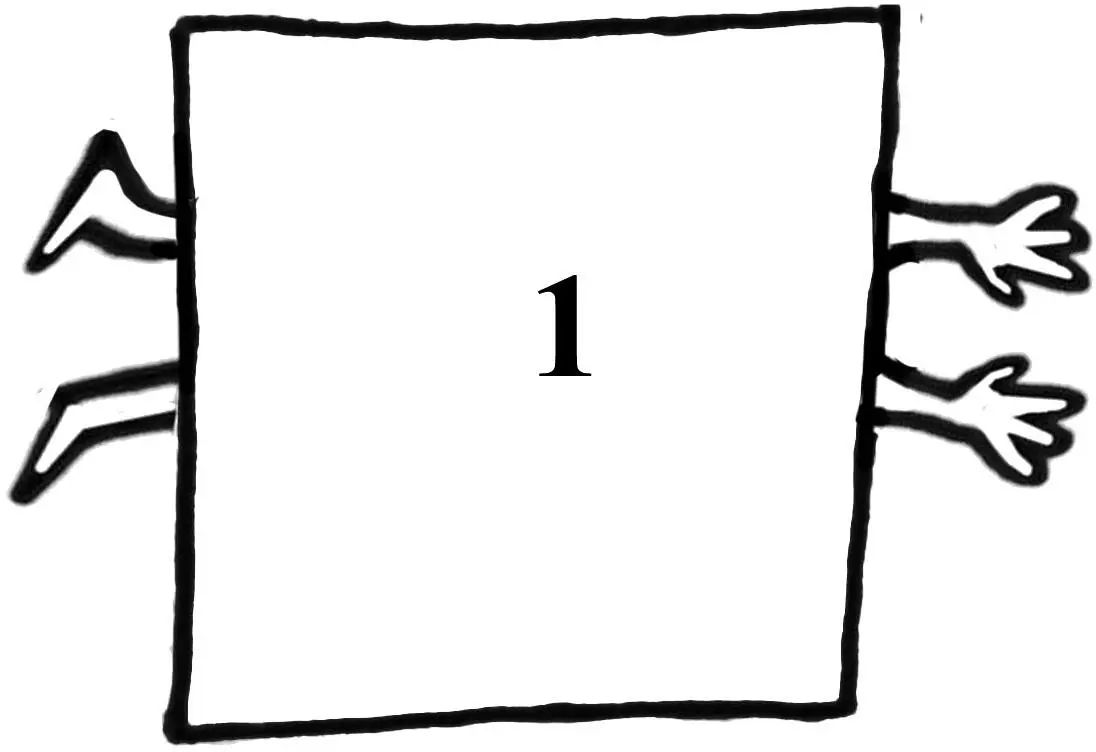

because the first four turns make a complete rotation, head over heels, back exactly to where we started, we ignore them as wasted effort, and just focus on the one left-over turn, which got us somewhere:

3 + 2 = 1

In this respect, rotating a square is the same as rotating the hour hand on an ordinary clockface. If it’s two o’clock and we add twelve hours, we don’t say it’s fourteen o’clock (unless we’re being tiresome). We say it’s two o’clock again.

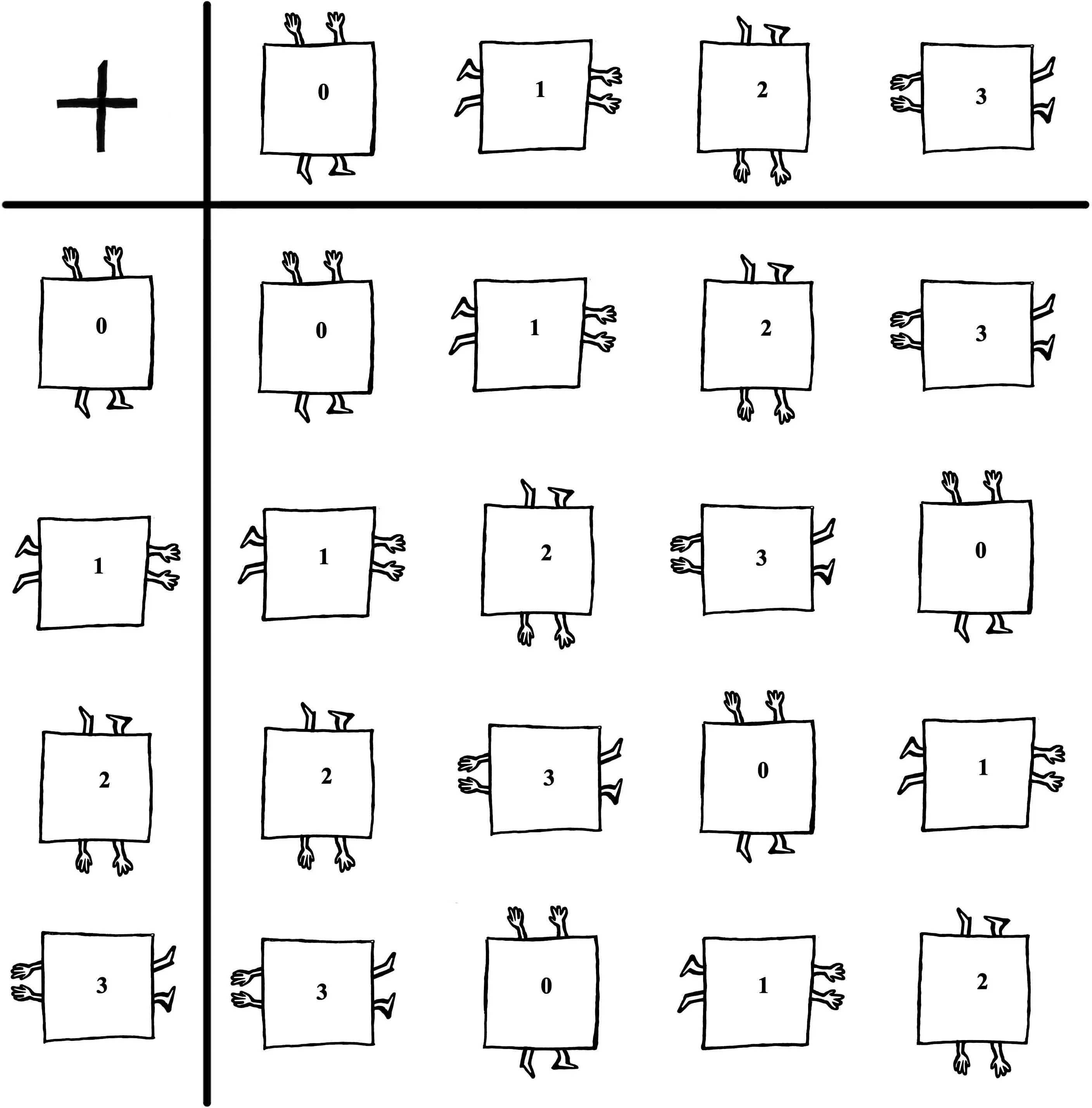

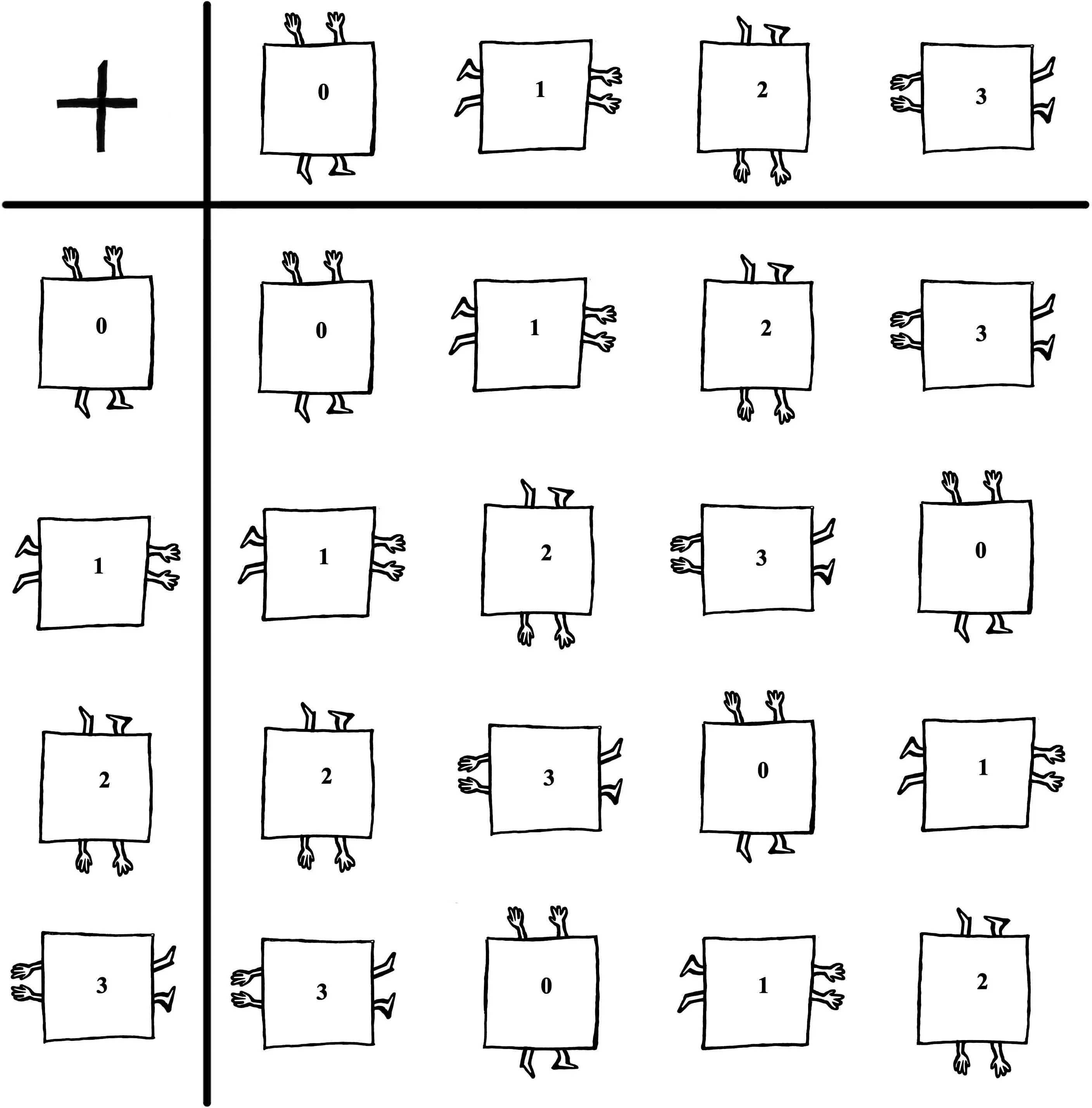

All these combinations of turns can now be written down as a chart. These tables are the lifeblood of Group Theory. Every mystery of this secretive, sly subject is contained in them. The one that applies to turns of a square is:

It’s read in the same way as the distance chart at the front of a road atlas. It’s not a calculating device; it’s a secretarial way of keeping track of information. If you’re six years old and want to remind yourself what happens when you turn a square once, then turn it again, i.e.:

take the row corresponding to 1, run your chocolatey finger along until you come to the column corresponding to 1, and there’s the answer – it’s equivalent to two turns:

What’s baffling is that there can be anything complicated enough about this ‘study’ of symmetries to bring it out of the playroom in the first place.

45

The papers that slosh about in the basement are (Simon insists I am to say) ‘carefully, hnnnh, arranged and, uuuh, being sorted in plastic bags’.

But I’ve put my foot down over this: ‘That’s a lie, Simon. You’re telling me to make things up.’

‘I’ve not noticed your reluctance on that front before.’

Simon was taught mathematics by the number 45.

The first written evidence we have of 45’s significance in his life comes from an Atlantic blue notebook dated January 1956 (a year before Simon started school) and entitled

Inside, Simon addresses mathematical problems to this number:

(sums for 45, you 45)

performs amusing numerical games:

and emerges briefly, porpoise-like, from his researches to write letters to her:

Translation: My darling 45 I cried when you went out I had tea and played with you before you go 45 and 47 29 say 1 2 3 82 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 111

before re-submerging in a glug of numbers.

Sometimes, 45 wrote back:

45 was Simon’s number for his mother. She was the one who taught him maths, up to quadratic equations. Astounding, for a British housewife in the 1950s – no one in the family can explain it.

Once the first Atlantic blue notebook was finished, Simon and his mother started another, in February 1956, just before his fourth birthday. Her handwriting is on the cover this time, and she calls him a monkey:

I wonder who crossed this fondness out.

Once, during these pre-school years, Simon was distracted by a word:

But he soon snapped back to numbers with gusto:

9 eSimon

Simon has five types of grunt:

Ask him about his mother,

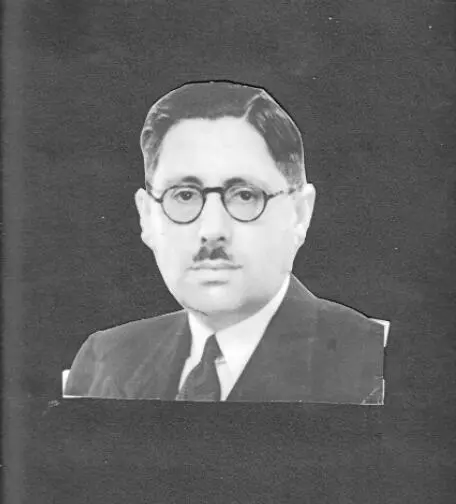

his father,

or his parents’ marriage,

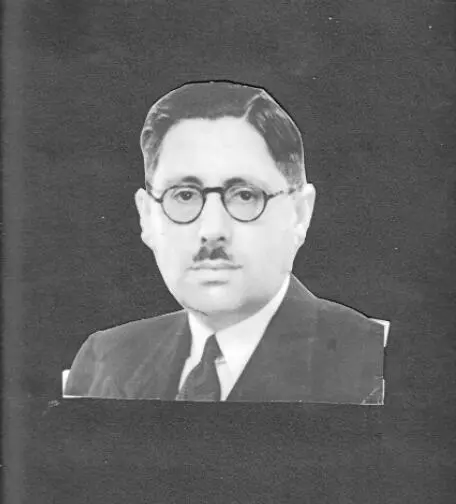

and you get a happy grunt for the first, a puzzled one for the second, and an incomprehensible bleat concerning the photo above.

It’s possible to extract more interpretation, if you work at it.

‘Simon, what do you mean, “Uuug heugh … gghuaha … ehh ghH ”?’

‘Haaaghuggh … oooh … ghughghEH.’

‘These are your parents. You grew up with them. Is this photo an accurate reflection of their relationship or not?’

‘Aaaghurghh … gghahuugh … eeehghuGH … is that a dog in the middle? Oh, it’s a bag. If it had been a dog these might not have been my parents, just people who looked like my parents, because we didn’t have a dog.’

‘Don’t you think there’s something remarkable about this picture? Sitting back to back on a pebble beach in Southern England with something that looks like a dead bulldog between you?’

Simon looks trapped and panicky.

‘Or is this just a snapshot of what marriage always is, to you?’

The grunt-bleat means bafflement. Why should he find something odd about the photograph? It’s a photograph: one of those things (so rare in life) in which a fact is made immutable. Why muddy it with interpretation? Why, if you do muddy it, pick on that particular interpretation? It could be one of a million others.

Simon is, verbally, one of the most adept and playful people I know – as long as he doesn’t have to speak.

Or use metaphor.

Or comment on photographs.

Simon’s parents’ marriage (according to other members of the family) was not happy or unhappy, just mannered and soulless.

The puzzled father-grunt Simon gives about his father signifies a lack of interest. The happy mother-grunt, ‘loveliness’. Loveliness is the only adjective Simon associates with Helene Norton. She ‘embodied’ the word, he says. There isn’t need for others – and he doesn’t mean ‘loveliness’ because of her startling beauty, which Simon claims he’d never noticed until I started ogling her, but ‘loveliness’ because of … because of … uuuggg hhhAH ! Grunt Number Four: Frustrated Grunt.

What’s the point of me demanding new words when he’s already given me the one that works to perfection?

‘Loveliness’ does not mean uncensoriousness, however. When his mother was alive, Simon used to visit her in London every two or three weeks, but she refused to greet him until he’d had a bath.

Then she would criticise his clothes.

‘If it wasn’t one thing, it was another,’ remembers Simon forlornly. ‘I got the feeling I could never satisfy her. Did it count if your clothes were wrong in the period before you’d had a chance to spruce up between the front door and the bath?’

After trying to ‘spruce up’ he’d step out of the bathroom in the fresh clothes that his mother kept in a cupboard, ready for his visits, and expecting now to be allowed to kiss her hello. ‘But I’d almost certainly forget something, and she’d draw attention to that one thing and home in on it. My shirt was wrong, or my shoelaces were undone. I hadn’t done up my trousers correctly.’

He gives a purgatorial groan.

‘It was too much for me.’

Two or three days after his mother’s death (Simon remembers it as ‘rather too quickly’) he and his two brothers let themselves into her five-bedroom apartment near Baker Street, and began picking over her possessions. From their mother’s cupboards and drawers they extracted everything small and unbreakable and piled it on the floor. Then they shuffled among the piles – in my image of this spectral, sacrificial scene I imagine them as three tall birds, and hear the clicking of their feet on the parquet floors – plucking up anything that took their fancy.

Читать дальше