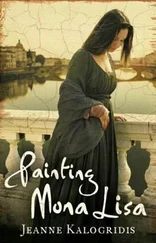

Late on the morning of the fifth day, we passed over a series of gentle hills; at the apex of the last one, I spied Florence, nestled in the basin below, and let go a gasp of appreciation. Beneath a dazzling blue sky, the city looked golden, its southern flank bisected by the winding silver Arno. As we descended, the separate rooftops grew distinct, and the driver, who knew the city well, began to point out landmarks. The greatest of them, dominating the skyline, was the vast orange-red dome of the great cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore, Our Lady of the Lilies, matched in height only by its slender campanile; farther south lay the tower of the Palazzo della Signoria, the Palace of Lords, seat of the city’s government.

Most of the buildings were made of stone—some of the costly pietra serena, a dove gray rock that turned shimmering white in the strong sun, others of a pale brown or gold. Some were of stucco, but almost all had the same orange-red brick roof and were built in the classical style, which lent a pleasant uniformity. Perhaps it was the light or the clement weather or the languid hills that embraced the outskirts, but I judged Florence to be the prettiest city I had ever seen. Next to it, Milan seemed drab and cold and dirty.

We passed through the northern gate onto the broad, cobblestoned Via Larga, swarming with pedestrians, wagons, carriages, horses, and street merchants; the sun hung at mid-heaven, and all over the city, church bells were chiming to mark Sext, the sixth hour after sunrise. From the upper-floor windows of all the buildings, fluttering banners hung. Most bore the city standard, a bright red fleur-de-lis against a white background, or the Medici crest, a gold shield adorned with six balls, five of them red and the topmost blue, with tiny gold stylized lilies.

I was so exhilarated that I wanted to keep riding, but we arrived at San Marco all too quickly, and the wagon wheels slowed to a stop at last. I was disappointed; I had wanted a cathedral with a great dome and tall spires for Matteo, but instead saw a spare single-nave church with a bland stone façade, and tucked next to it, a square, plain, two-story cloister. I climbed down from the wagon, my legs wobbly from disuse, and waited with the horses while the driver entered the monastery.

He returned with a lay brother, Domenico, a cheerful young man with red curls who wore a white tunic and scapular beneath a black cape that fell below his ankles. Domenico led me just inside the cloister, to a public area known as the chapter house. He explained in a whisper that San Marco’s church and convent had been some two hundred years old when Lorenzo de’ Medici’s grandfather, Cosimo, paid for their renovation thirty years earlier; the crumbling wood and mortar were replaced by the more durable and handsome pietra serena and cream stucco.

I sat, only half listening as Domenico spoke in hushed tones. He told me that the abbot was expecting me, and that the next afternoon at None, the ninth hour after dawn, a service for Matteo would be held in the sanctuary, followed by burial in the churchyard. I left, relieved that I had survived the discussion without tears, and returned to the waiting driver, his wife, and the now-empty wagon.

We continued south down the wide Via Larga and the driver continued his narration. He pointed out the home of Lorenzo the Magnificent, an unremarkable, square, three-story fortress of stone, with the Medici banner hanging from every window.

The driver pointed straight ahead. “And that way lies the church of San Lorenzo, where Lorenzo’s father and grandfather are buried.”

We rolled past similar palazzos and gardens, then artists’ workshops, goldsmiths, and jewelers. Not long after, we approached the massive cathedral of Florence, also called the Duomo because of its magically unsupported dome, the largest in all the world. Across from it stood the pale stone octagon of the Baptistry of Saint John, its gilded bronze doors dazzling in the sun.

We turned east to drive alongside the long stone spine of the cathedral, and followed the road as it curved due south again. Eventually, we came to a grim, four-story fortress with a crenellated tower, which housed the city magistrate; there we veered sharply left onto the Via Ghibellina. A few minutes later, the driver pulled the horses over to the curb.

“The convent of Le Murate,” he announced, and hopped down from his seat to help me down.

I descended to find a long expanse of stone wall broken by a tall, narrow wooden gate. Two rusting iron grates, one at the level of my eyes, the other of my ankles, were set into the door; the uppermost grate was covered on the inside by a black cloth. While the driver waved down a street lad to help him fetch my trunk, I clanged the brass knocker and called out softly; as I did, I caught a sudden whiff of vinegar and felt inexplicably nauseated.

Within a few minutes, the gate opened far enough to allow the driver to shove my trunk inside the door, though he was not allowed entry himself. He promised to come for me the next afternoon, and as I passed through the convent walls I saw the vinegar—used to prevent plague—in a bucket that held alms thrown through the grate by passersby.

Le Murate was old but in good repair and very clean; the furnishings were spare but elegant and comfortable, even by the court of Milan’s standards. The abbess, who had received Bona’s letter, welcomed me personally and gratefully accepted the duchess’s generous donation, which I pressed into her palm. Even so, the place evoked a strange anxiety in me.

I went at once to the cell assigned me, closed my door, and studied the star rituals written in Matteo’s hand. “For banishing,” he had written beneath the first, “start here.” I was not certain I wanted to know what needed banishing, but the alternative was to sit and think deeply on the funeral that was to come. I chose instead to practice drawing the five-pointed stars in the air with my index finger, the way I had seen Matteo do it in the darkness. I began, also, to memorize the strange words that went with the banishing. I did not emerge from my cell until supper; afterward I walked the grounds alone, and came upon the carefully tended gardens. In the center of them stood an unusual tree: a cedar, as tall as four men standing upon each other’s shoulders, its branches broad and sweeping.

The sight jolted me, as if I had seen Matteo himself standing there. I hurried to the tree and reached past the bristling blue-green needles to press my hand to the bark; it was ridged and rough, as I knew it would be, though I had supposedly never seen such a tree before. I leaned against it and drew in its pungent fragrance; tears came to my eyes as I heard a woman’s voice whisper in my memory.

A cedar of Lebanon.

My mother’s voice. The convent’s outer walls loomed close and began to spin; I closed my eyes, panicked. The Duomo’s red cupola, the cobblestoned streets, the whitewashed convent walls, even the grates on the door and the smell of vinegar . . . hadn’t I recognized them all?

I do not know this place, I told myself firmly, and hurried back to my cell through halls grown terrifyingly familiar.

That night, I silently performed Matteo’s banishing ritual, and did not emerge from my cell until the next day at half past two, when it was time to leave for my husband’s funeral.

The driver delivered me to the main entrance of the church of San Marco, where the redheaded Brother Domenico waited for me. He led me into a modest chapel, where a small candelabrum burned in front of a magnificent altarpiece painted with a scene of the Last Judgment. Nearby, a balding priest was lighting coals for the censer, muttering prayers as he did so. Two monks in white tunics and black capes stood together just left of the altar, and lowered their gazes as I entered.

Читать дальше