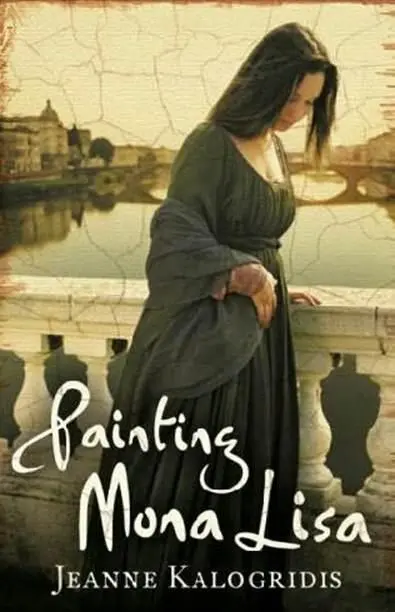

Jeanne Kalogridis

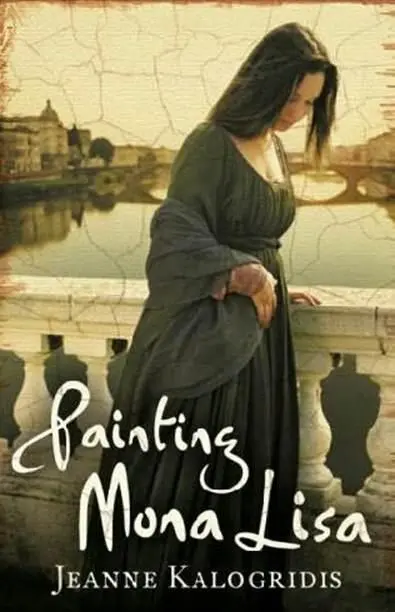

Painting Mona Lisa aka I, Mona Lisa

© 2006

I am extraordinarily indebted to the following people:

My husband, who not only survived cancer, chemotherapy, and complications this past year but, far more impressively, survived the writing of this novel with good humor and good grace;

My brilliant agents, Russell Galen and Danny Baror, who have both survived having me as a client for well over twenty years;

My friends Kathleen O’Malley and Anne Moroz, who bravely waded through this daunting manuscript and kindly offered their comments; and most of all:

My editors, Charles Spicer at St. Martin’s Press and Emma Coode at HarperCollins UK, both consummate professionals gifted with infinite patience. Charlie and Emma each went to extraordinary lengths so that I could spend time caring for my husband during his illness. The book was, as a result, abysmally late. I wish I knew words that could convey the depth of my gratitude for their kindness, and my regret that they were pushed to the limit in order to ready the manuscript for the printer. For them, I have these words: Thank you, Charlie. Thank you, Emma.

Things that happened many years ago often seem

close and nearby to the present, and many things

that happened recently seem as ancient as the

bygone days of youth.

– Leonardo da Vinci

Codex Atlanticus, fol. 29v-a

Lisa

JUNE 1490

M y name is Lisa di Antonio Gherardini, though to acquaintances I am known simply as Madonna Lisa, and to those of the common class, Monna Lisa.

My likeness has been recorded on wood, with boiled linseed oil and pigments dug from earth or crushed from semiprecious stones and applied with brushes made from the feathers of birds and the silken fur of animals.

I have seen the painting. It does not look like me. I stare at it and see instead the faces of my mother and father. I listen and hear their voices. I feel their love and their sorrow, and I witness, again and again, the crime that bound them together; the crime that bound them to me.

For my story begins not with my birth but a murder, committed the year before I was born.

It was first revealed to me during an encounter with the astrologer two weeks before my birthday, which was celebrated on the fifteenth of June. My mother announced that I would have my choice of a present. She assumed that I would request a new gown, for nowhere has sartorial ostentation been practiced more avidly than my native Florence. My father was one of the city’s wealthiest wool merchants, and his business connections afforded me my pick of sumptuous silks, brocades, velvets, and furs.

But I did not want a gown. I had recently attended the wedding of my uncle Lauro and his young bride, Giovanna Maria. During the celebration afterward, my grandmother had remarked sourly:

“It cannot last happily. She is a Sagittarius, with Taurus ascendant. Lauro is Aries, the Ram. They will constantly be butting heads.”

“Mother,” my own had reproached gently.

“If you and Antonio had paid attention to such matters-” My grandmother had broken off at my mother’s sharp glance.

I was intrigued. My parents loved each other, but had never been happy. And I realized that they had never discussed my stars with me.

When I questioned my mother, I discovered that my chart had never been cast. This shocked me: Well-to-do Florentine families often consulted astrologers on important matters, and charts were routinely drawn up for newborns. And I was a rare creature: an only child, the bearer of my family’s hopes.

And as an only child, I was well aware of the power I possessed; I whined and pleaded pitifully until my reluctant mother yielded.

Had I known then what was to follow, I would not have pressed so hard.

Because it was not safe for my mother to venture out, we did not go to the astrologer’s residence, but instead summoned him to our palazzo.

From a window in the corridor near my bedroom, I watched as the astrologer’s gilded carriage, its door painted with his familial crest, arrived in the courtyard behind our house. Two elegantly appointed servants attended him as he stepped down, clad in a farsetto , the close-fitting man’s garment which some wore in place of a tunic. The fabric was a violet velvet quilt, covered by a sleeveless brocade cloak in a darker shade of the same hue. His body was thin and sunken-chested, his posture and movements imperious.

Zalumma, my mother’s slave, moved forward to meet him. Zalumma was a well-dressed lady-in-waiting that day. She was devoted to my mother, whose gentleness inspired loyalty, and who treated her slave like a beloved companion. Zalumma was a Circassian, from the high mountains in the mysterious East; her people were prized for their beauty and Zalumma-tall as a man, with black hair and eyebrows and a face whiter than marble-was no exception. Her tight ringlets were formed not by a hot poker but by God, and were the envy of every Florentine woman. At times, she muttered to herself in her native tongue, which sounded like no language I had ever heard; she called it “Adyghabza.”

Zalumma curtsied, then led the man into the house to meet my mother. She had been nervous that morning, no doubt because the astrologer was the most prestigious in town and had, when the Pope’s forecaster had taken ill, even been consulted by His Holiness. I was to remain out of view; this first encounter was a business matter, and I would be a distraction.

I left my room and stepped lightly to the top of the stairs to see if I could make out what was going on two floors below me. The stone walls were thick, and my mother had shut the door to the reception chamber. I could not even make out muffled voices.

The meeting did not last long. My mother opened the door and called for Zalumma; I heard her quick steps on the marble, then a man’s voice.

I retreated from the stairs and hurried back to the window, with its view of the astrologer’s carriage.

Zalumma escorted him from the house-then, after glancing about, handed him a small object, perhaps a purse. He refused it at first, but Zalumma addressed him earnestly, urgently. After a moment of indecision, he pocketed the object, then climbed into his carriage and was driven away.

I assumed that she had paid him for a reading, though I was surprised that a man with such stature would read for a slave. Or perhaps my mother had simply forgotten to pay him.

As she walked back toward the house, Zalumma happened to glance up and meet my gaze. Flustered at being caught spying, I withdrew.

I expected Zalumma, who enjoyed teasing me about my misdeeds, to mention it later; but she remained altogether silent on the matter.

T hree days later, the astrologer returned. Once again, I watched from the top-floor window as he climbed from the carriage and Zalumma greeted him. I was excited; Mother had agreed to call for me when the time was right. I decided that she wanted time to polish any negative news and give it a rosier glow.

This time the horoscopist wore his wealth in the form of a brilliant yellow tunic of silk damask trimmed with brown marten fur. Before entering the house, he paused and spoke to Zalumma furtively; she put a hand to her mouth as if shocked by what he said. He asked her a question. She shook her head, then put a hand on his forearm, apparently demanding something from him. He handed her a scroll of papers, then pulled away, irritated, and strode into our palazzo. Agitated, she tucked the scroll into a pocket hidden in the folds of her skirt, then followed on his heels.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу