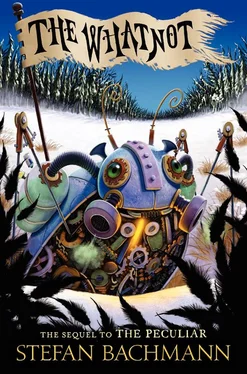

The wings were huge, ruffled with dark, spiny feathers, and the blue-lipped mouth was riddled with teeth. A black tongue flicked from it every few seconds. But when Pikey peered at the faery it didn’t look as if it were about to gnaw his leg off. Rather, it looked as if it were about to drip into a puddle. One of its wings hung limp, the feathers smashed. The bone was bent at a hideous angle.

Pikey eyed the creature as it pulled itself up the stairs, keeping his bread safely behind his back. The faery might not seem dangerous, but faeries could look however they wanted to look if it suited their fancy. He wasn’t about to fall for any hookem-snivey.

“Boy?” it said in a high, whistling voice. “Boy?”

Just like a baby, Pikey thought. He frowned.

“Boy?” It had reached the seventh step. It stretched a thin-fingered hand up toward Pikey, pleading.

“What d’you want?” Pikey asked gruffly. He shoved the bread into his pocket and glanced around to make sure no one was near. Fraternizing with faeries was dangerous. If anyone so much as smelled of spells or piskie herbs, it was off to Newgate, and Pikey had heard there was a kindly looking old man there in a butcher’s apron, and he was always weeping, and he would weep and weep as he pulled your fingernails out, but he would interrogate you until you’d say anything. Then you’d be sent to a different prison. Or hanged. Whatever the case, you were in for it. Pikey had been in for it all day, and he’d had enough.

The faery continued up the steps, its round eyes locked on his.

“What?” Pikey snapped. “You can’t have my bread if that’s what you want. I ran a long way for it. Go away.”

“Boy,” it said, yet again. “ Wing.”

“Yeh, looks broken to me. Rotten luck.” Some servant in the downstairs had probably caught it stealing and had smashed it with a frying pan. Served it right, too.

“Help.” The faery was on the step below Pikey now, looking up at him with great mirror eyes that seemed to grow larger with every breath.

“I ain’t helping you.” Pikey turned his face away. His gaze flickered back. He didn’t want to be awful. But he wasn’t about to put his neck out for a faery. Someone might be watching from one of those glowing windows. A street sweeper might pass just in that instant. Pikey couldn’t be seen with it. It was hard enough staying alive with one eye looking like a puddle of rain.

“Please help?” The voice was so human now; it sent a little stab through Pikey’s heart despite himself. The faery was just bones, a few thin sticks wrapped in papery skin. And it was hurting. He wouldn’t leave a dog like that. He wouldn’t even leave a leadface like that.

He frowned harder and joggled his knee. Then he leaned forward and took the damaged wing in his hand. The faery shied ever so slightly at his touch, but it did not pull away.

“Fine,” Pikey said. “But if someone sees, I’m going to shove you at ’em and get outta here, you hear me?”

The feathers felt smooth and oily between Pikey’s fingers, strangely immaterial, like smoke. He felt gently along the bone. He didn’t know a great deal about doctoring, but Bobby Blacktop, the old chemist’s boy, had gotten run over by a gas trolley a year ago and had both his legs broken. Pikey had learned a few things from that.

Suddenly the faery sat up, ears twitching, as if picking up a sound only it could hear. “Quickly,” it hissed. “Quickly!”

“Ow, aren’t you one to make demands. What’s the hurry, then? Where you gotta be?” Pikey’s fingers found the joint, clicked it back in place. “It was just banged out o’ the socket is all. Is that better? Does it work now?”

The faery’s eyelids snapped, once, across its eyes. In a flash its wings unfurled, faster than Pikey would have thought possible. He jerked back. The faery peered at him a second longer, its tongue slithering between its teeth. Then it whirled, wrapping itself in its feathers. There was a brush of wind, a chorus of whispers, like many little voices calling to one another, and then the faery was gone.

It didn’t exactly vanish. Pikey thought it might have, but it was more as if it had moved into a pocket, as if the stairs and the street and all of London were painted on the thinnest of veils and the faery had simply slipped behind it.

Pikey stared at the place where it had been. Then he stood quickly. Lights were coming on in the servants’ hall below. He could hear voices raised in excitement, the clatter of metal. A hand began to fiddle with the lacy curtains over the window.

Time to go, Pikey thought. He vaulted over the railing and set off briskly along the side of the street.

But he had only taken a few steps when a deep, skull-shivering shudder almost tossed him from his feet. He stumbled. The shudder grew in strength, pounding and stamping louder than all the steam engines of King’s Cross station, all going at once.

Pikey turned. It was the house. Fissures were racing up the windows, splitting smaller and smaller. The walls shook and swelled, as if something were straining against them from inside. And then, with an almighty shriek, every window in the house burst outward. All those bright windows, exploding into the night in sprays of gold. The roof blew into the sky. Stone rained down, glass and green metal and shreds of colored silk. Pikey yelled and raced into the street, dodging the falling debris.

An oil trolley skidded around him. Steam coaches honked, belching fumes. Men leaned out of vehicles, ready to shout at Pikey, but their words stuck in their throats. All eyes turned to Wyndhammer House.

Piercing wails were coming from within, swooping down the winter street. There was another resounding boom . And then the house began to fall.

IX days and six nights Hettie and the faery butler had walked under the leafless branches of the Old Country, and still the cottage looked no closer than when they had first laid eyes on it.

IX days and six nights Hettie and the faery butler had walked under the leafless branches of the Old Country, and still the cottage looked no closer than when they had first laid eyes on it.

Of course, Hettie didn’t know if it had been six nights. It always felt like night in this place, or at least a gray sort of evening. The sky was always gloomy. The moon faded and grew, but it never went away. She trudged after the wool-jacketed faery, over roots and snowdrifts, and the little stone cottage remained in the distance, unreachable. A light burned in its window. The black trees formed a small clearing around it. Sometimes Hettie thought she saw smoke rising from the chimney, but whenever she really looked, there was nothing there.

“Where are we going?” she demanded, for the hundredth time since their arrival. She made her voice hard and flat so that the faery butler wouldn’t think she was frightened. He better think she could smack him if she wanted to. He better.

The faery ignored her. He walked on, coattails flapping in the wind.

Hettie glared and kicked a spray of snow after him. Sometimes she wondered if he even knew. She suspected he didn’t. She suspected that behind the clockwork that encased one side of his face, behind the cogs and the green glass goggle, he was just as lost and afraid as she was. But she didn’t feel sorry for him. Stupid faery. It was his fault she was here. His fault she hadn’t jumped when her brother Bartholomew had shouted for her. She might have leaped to safety that night in Wapping, leaped back into the warehouse and England. She might have gone home.

Читать дальше

IX days and six nights Hettie and the faery butler had walked under the leafless branches of the Old Country, and still the cottage looked no closer than when they had first laid eyes on it.

IX days and six nights Hettie and the faery butler had walked under the leafless branches of the Old Country, and still the cottage looked no closer than when they had first laid eyes on it.