1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...18 One of the reasons that repetition is so important lies in your teenager’s brain development. One of the frontal lobes’ executive functions includes something called prospective memory, which is the ability to hold in your mind the intention to perform a certain action at a future time—for instance, remembering to return a phone call when you get home from work. Researchers have found not only that prospective memory is very much associated with the frontal lobes but also that it continues to develop and become more efficient specifically between the ages of six and ten, and then again in the twenties. Between the ages of ten and fourteen, however, studies reveal no significant improvement. It’s as if that part of the brain—the ability to remember to do something—is simply not keeping up with the rest of a teenager’s growth and development.

The parietal lobes, located just behind the frontal lobes, contain association areas and are crucial to being able to switch between tasks, something that also matures late in the adolescent brain. Switching between tasks is nearly a constant need in today’s world of information overload, especially when you consider the fact that multitasking—doing two cognitively complex things at the same time—is actually a myth. Chewing gum and doing virtually anything else is not multitasking because chewing gum involves no real cognitive focus. Both talking on a cell phone and driving, however, do involve cognitive focus. Because there are limits to how many things the human brain can focus on at any one time, when someone is engaged in multiple cognitively significant activities, like talking and driving, the brain must constantly switch back and forth between the two tasks. And when it does, neither of those tasks is being accomplished particularly well.

The parietal lobes help the frontal lobes to focus, but there are limits. The human brain is so good at this juggling that it seems as though we are doing two tasks at the same time, but really we’re not. Scientists at the Swedish medical university Karolinska Institutet measured those limits in 2009 when they used fMRI images of people multitasking to model what happens in the brain when we try to do more than one thing at a time. They found that a person’s working memory is capable of retaining only between two and seven different images at any one time; this means that focusing on more than one complex task is virtually impossible. Focusing chiefly happens in the parietal lobes, which dampen extraneous activity to allow the brain to concentrate on one thing and then another.

The problem of having immature parietal lobes was illustrated in a segment on Good Morning America in May 2008 by the ABC TV correspondent David Kerley and his teenage daughter Devan. Using a course set up by Allstate Insurance, and with her father in the passenger seat, Devan, who had been driving for a year, was instructed about speed, braking, and turning and allowed to take a practice run through the course. Then she was given a series of three “distractions” to handle while navigating the course’s twists and turns. First, she was handed a BlackBerry and told to read the text on the screen while driving. She hit several cones. Next, three of her friends were put in the backseat and a lively conversation ensued. Devan hit more cones. Finally, Devan was handed a package of cookies and a bottle of water, and just passing the cookies around and holding the bottle of water caused her to run over several more cones. Multitasking is not only a myth but a dangerous one, especially when it comes to the teenage brain.

“Multitasking” has become a household word. The research in Sweden suggests that there are limits. Teenagers and young adults pride themselves on their ability to multitask. Have today’s teens and young adults imprinted on a multitasking world? Maybe. In studying how young adults these days handle distractions, researchers at the University of Minnesota have shown that the ability to successfully switch attention among multiple tasks is still developing through the teenage years. So it may not come as a surprise to learn that of the nearly six thousand adolescents who dieevery year in automobile accidents, 87 percent die because of distracted driving.

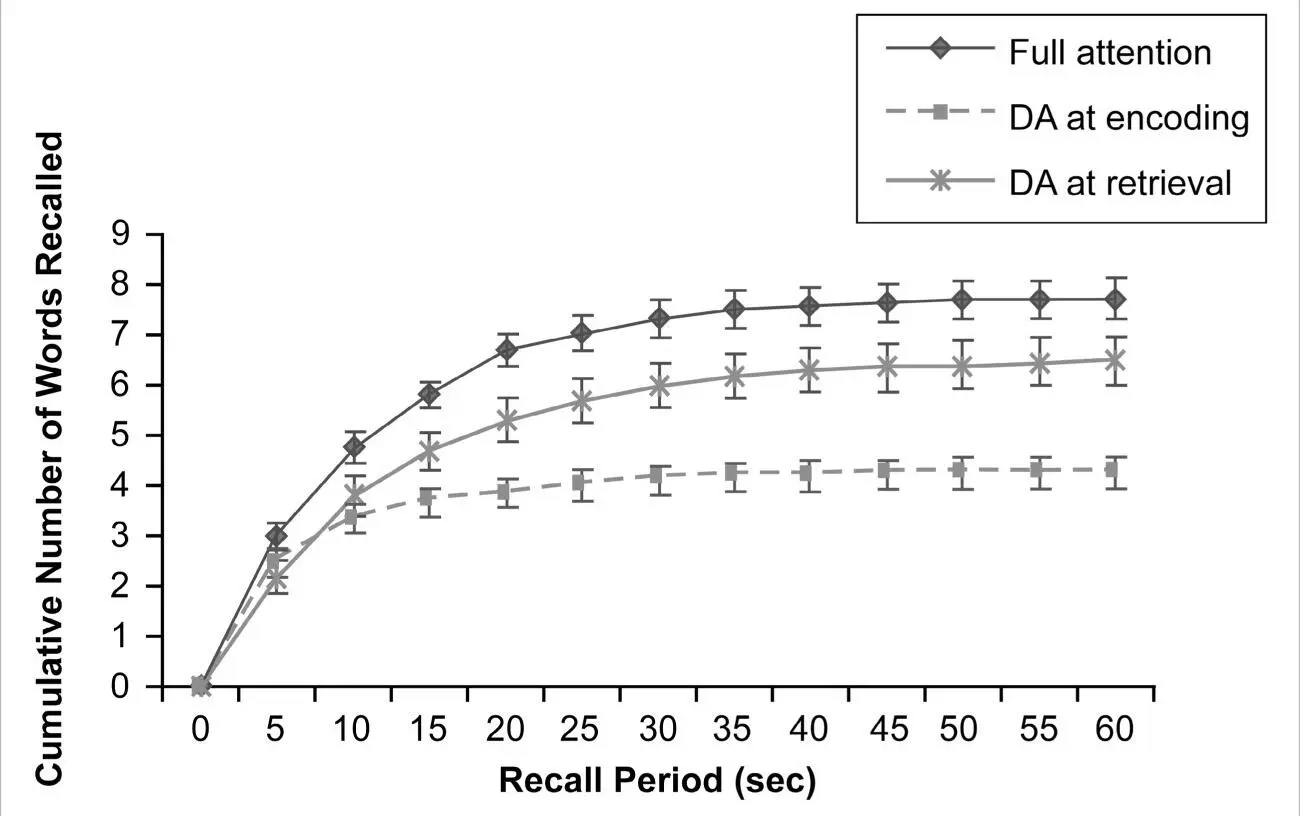

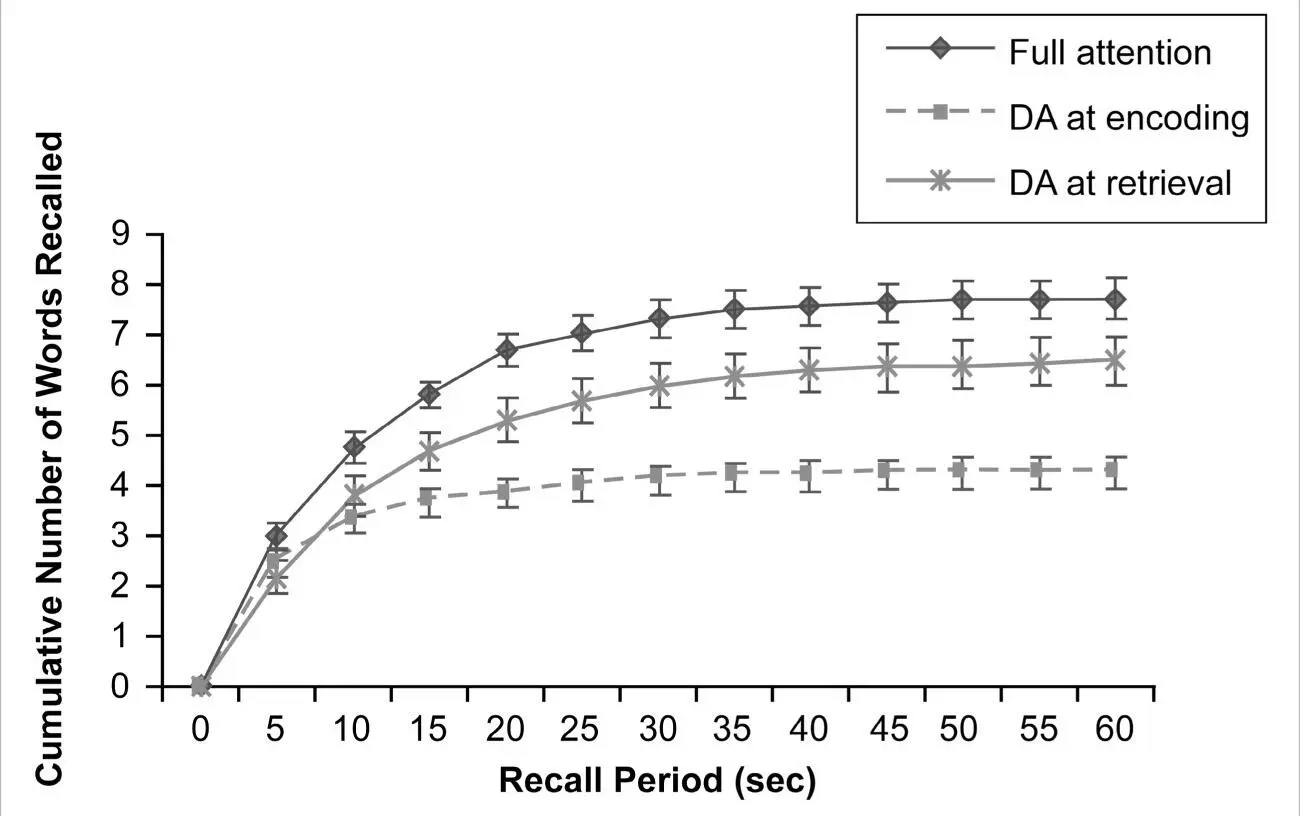

The question of whether today’s teens and young adults have a special skill set for learning while distracted was more formally tested in 2006 by researchers at the University of Missouri. They took twenty-eight undergraduates, including kids in their late teens, and asked them to memorize lists of words and then recall these words at a later time. To test whether distraction affected their ability to memorize, the researchers asked the students to perform a concurrent task—placing a series of letters in order based on their color by pressing the keys on a computer keyboard. This task was given under two conditions: when the students were memorizing the lists of words and when the students were recalling those lists for the researchers. The Missouri scientists discovered that simultaneous tasksaffected both encoding (memorizing) and retrieving (recalling). When the keyboard task was given while the students were trying to recall the previously memorized words (which is akin to taking a test or exam), there was a 9 to 26 percent decline in their ability to memorize the words. The decline was even more if the concurrent distracting task occurred while they were memorizing, in which case their performance decreased by a whopping 46 to 59 percent.

These results certainly have implications for the teen bedroom during a homework night! I not-so-fondly remember walking in on my sons during evening homework time to find them with the television on, headphones attached to iPods, all the while messaging someone on the lower corner of their computer screens and texting someone else on their iPhones. It wasn’t a problem, they protested, when I suggested they concentrate on their homework, assuring me their course reviews for the next day’s exams were totally unaffected by the thirty-two other things they were doing at the same time. I didn’t buy it. So I buttressed my argument with the Missouri data. I put Figure 5in this book in case you want to use it to make the same point to your teen.

FIGURE 5. Multitasking Is Still Not Perfect in the Teen Brain:College students were tested under three conditions: No Distraction (full attention), Distracted Attention (DA) when memorizing (DA at encoding), and Distracted Attention when recalling (DA at retrieval). Students performed poorly when multitasking during recall, and even worse when they multitasked while memorizing.

Attention is only one way we can assess how the brain is working. There’s a lot more under the hood of the brain than just the four lobes, so returning to Figure 3let’s start at the back, where we find the brainstem at the very bottom of the brain, attached to the spinal cord. The brainstem controls many of our most critical biological functions, like breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, and bladder and bowel movements. The brainstem is on “automatic”—you are not even aware of what it does, and you normally don’t voluntarily control what it does. The brainstem and spinal cord are connected to the higher parts of the brain through way station areas, like the thalamus, which sits right under the cortex. Information from all the senses flows through the thalamus to the cortex. Right below the cortex are structures called the basal ganglia, which play a big role in making coordinated and patterned movements. The basal ganglia are directly affected by Parkinson’s disease and account for the trembling and the appearance of being frozen, or unable to move, which are the hallmark symptoms of Parkinson’s patients.

Читать дальше