This sounds, indeed is, severely critical. It is no more than he deserves but, over the last twenty years, he has been subjected to attacks far more violent than his performance in fact merits. Most of the emphasis has been on his alleged sympathy for the German cause before and during the Second World War. As Prince of Wales, it is claimed, he had condoned, indeed applauded, the rise of National Socialism. As King he was an arch-appeaser, energetically intervening to ensure that his ministers did not react robustly to the German occupation of the Rhineland. As Duke of Windsor he wittingly betrayed secrets of military importance to the Germans in 1939 and 1940, while in Spain and Portugal he flirted with German emissaries who suggested that he remain in Europe and hold himself in readiness for his return to an occupied Britain. Until well on into the war he maintained that Britain must inevitably be defeated and that a negotiated peace was the only sane way forward. At any time, it was suggested, he would have been ready to supplant his brother and take back the throne if the opportunity had arisen. Such attacks reached a peak with a television programme entitled Edward, the Traitor King , without even the courtesy of a question mark. His great-nephew, Prince Edward, in 1996 made a valiant effort to retrieve the situation with another television programme showing the Duke in a rather more positive light. But, as is usually the case, the spreading of muck proved more effective than the subsequent sponging operation.

I would not pretend that the Foreign Office papers that have been released in recent years show the Duke in a particularly flattering light. They deal mainly with the period when he was in France in 1939 and 1940 with a Military Mission charged vaguely with liaison with the French; his escapades in Spain and Portugal after the fall of France; his time as Governor of the Bahamas; and his financial problems during that period and after the war was over. It was my study of these papers that convinced me that he was often, though by no means invariably, silly, indiscreet and egotistical, and that by 1936 he was unfit to occupy the throne. In particular, in Spain and Portugal, his behaviour was such as to give German agents – anxious to feed their superiors in Berlin the news that they wanted to hear – some reason for hoping that he might rally to the Axis cause if the circumstances were right. But German official documents published since the war show that this was mere supposition, and that there is no hard evidence to support the thesis of treachery, be it actual or potential.

Ah yes, say the Duke’s detractors, but the published documents do not tell the whole story. King George VI sent the royal librarian, Owen Moreshead, and the art historian (and, as it later transpired, Communist spy) Anthony Blunt on a secret mission to secure the papers that would have proved the Duke’s guilt and bring them back for destruction or incarceration in some inaccessible vault at Windsor. The fact that the mission was far from secret; that its task was to bring back certain nineteenth-century family papers – mainly letters from Queen Victoria to her eldest daughter, the Empress Frederick; that all these papers were eventually returned to Germany; and that a complete inventory exists of everything that was brought back has not been allowed to spoil a good story.

To reach the conclusion that the Duke of Windsor was a traitor it is necessary to credit every surmise of those who wanted him to be so and to ignore the testimony of all those who worked with him and who knew him best. Even then there would be no proof. It is a cardinal principle of British law that an accused is assumed innocent until proved guilty. In the case of the Duke of Windsor the reverse has been true; he has been assumed guilty because he cannot positively be proved innocent. And yet to prove that somebody did not do something is notoriously difficult: for a single crime an alibi can with luck be established, but if a pattern of behaviour or of thought is in question it is generally impossible to do more than establish a balance of probabilities, based on one’s knowledge of the person concerned. I make no claim to omniscience, but I probably know more about the Duke of Windsor than anyone else alive. I am absolutely certain that, with all his faults, he was a patriot who would never have wished his country to be defeated or have contemplated returning to an occupied Britain as a puppet king. I accept that I cannot prove my contention, but I have much better grounds for maintaining it than any of those who have asserted the contrary over the last twenty years. Nothing that they have said or written has caused me to change my mind.

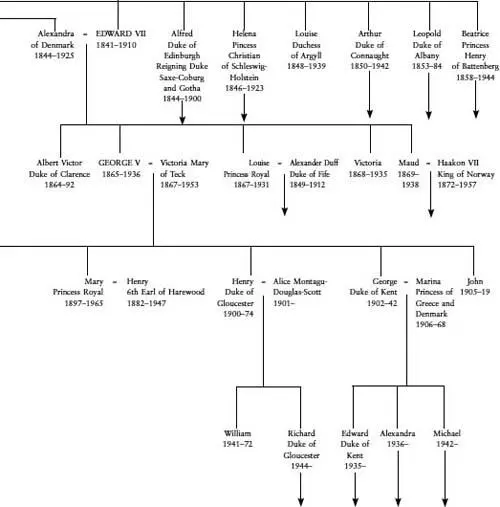

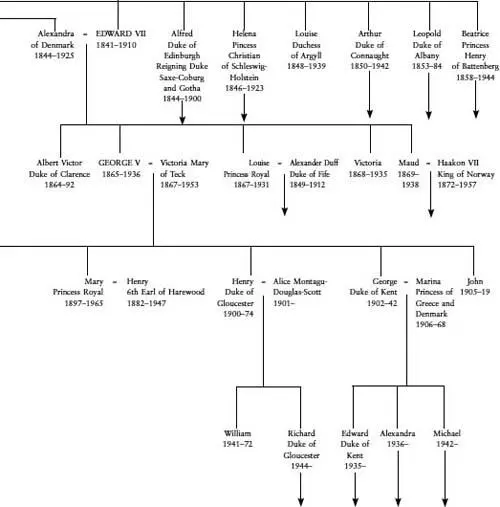

EVEN IN THE TWILIGHT OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY TO BE one of the 540 or so *1living and legitimate descendants of Queen Victoria is a matter of some moment. To have been born in 1894, eldest son of the eldest surviving son of the eldest son of the Queen Empress, was to be heir to an almost intolerable burden of rights and responsibilities.

Queen Victoria had then been on the throne for fifty-seven years. The great majority of her subjects had no recollection of another monarch. She had weathered the unpopularity which had grown up when she retreated into protracted seclusion after the death of the Prince Consort and now enjoyed unique renown. The Widow of Windsor, ruler of a vast empire and grandmother to half the crowned heads of Europe, was a bewitching figure; her obstinate refusal to play to the gallery had eventually won her the reverent respect of all but a tiny republican minority among her people. She had become a myth in her own lifetime.

To have a myth as a mother is not necessarily a prescription for a happy family life. In 1894 the future King Edward VII had already been Prince of Wales for more than fifty years. The role is never an easy one to fill, and in Edward’s case was made almost impossible by the carping censoriousness of his parents. The Prince of Wales gave them something to censure – he was self-indulgent, indolent and licentious – but he was also uncommonly shrewd and well able to do a useful job of work if given the chance. The Queen gave him as few chances as possible. She treated him as an irresponsible delinquent, and in doing so ensured that his irresponsibility and delinquency became more marked. It was not until he at last succeeded to the throne that his qualities as a statesman were given a proper chance to flourish.

In 1863 he married Princess Alexandra of Denmark – ‘Sea-King’s daughter from over the sea’ – radiantly beautiful and with a sweetness of nature which enabled her to endure her husband’s infidelity with generosity and dignity. She was capable of great obstinacy and occasional selfishness but she was still one of the most endearing figures to have sat upon the British throne. She rarely read, her handwriting would have disgraced an intoxicated spider, increasing deafness cut her off from society, but she enjoyed a vast and justified popularity until the day she died.

The first duty of an heir to the throne is to ensure the succession. The Prince and Princess of Wales did their best, producing two sons, three daughters, and then another short-lived son. Unhappily, however, their eldest son, Prince Albert Victor, always known as Eddy, proved an unhopeful heir for the throne of England. Languid and lymphatic – ‘ si peu de chose , though as you say a “Dear Boy”’, the Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz brutally dismissed him 1– he deplored the strident jollity of his family and preferred to trail wistfully in the wake of whatever unsuitable woman had attracted his attention. A determined and reliable wife seemed the only hope for his redemption, and a paragon was found in Princess Victoria Mary – May to the family – only daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Teck.

Читать дальше