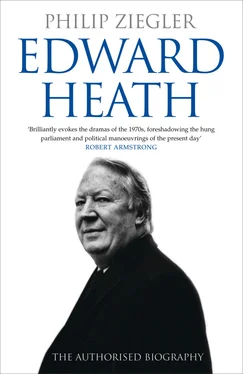

Edward Heath

The Authorised Biography

Philip Ziegler

Harper Press

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Harper Press in 2010

Copyright © 2010 Philip Ziegler

FIRST EDITION

Philip Ziegler asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © JULY 2010 ISBN: 9780007412204

Version: 2019-09-30

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Find out more about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

To Clare

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

FOREWORD

ABBREVIATIONS USED IN TEXT

ONE The Child and the Boy

TWO Balliol

THREE War

FOUR In Waiting for Westminster

FIVE The Young Member

SIX Chief Whip

SEVEN Europe: The First Round

EIGHT Minister

NINE Leader of the Opposition

TEN Problems with the Party

ELEVEN Victory

TWELVE Making a Ministry

THIRTEEN The Pains of Office

FOURTEEN Europe: The Second Round

FIFTEEN Ulster

SIXTEEN Choppy Water

SEVENTEEN The Approaching Storm

EIGHTEEN Foreign Affairs

NINETEEN Hurricane

TWENTY Defeat on Points

TWENTY-ONE The Uneasy Truce

TWENTY-TWO Defeat by Knockout

TWENTY-THREE Adjusting to a New Life

TWENTY-FOUR The Long Sulk

TWENTY-FIVE Phased Retreat

TWENTY-SIX Filling in Time

TWENTY-SEVEN Declining Years

NOTES

SOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

Edward Heath changed the lives of the British people more fundamentally than any prime minister since Winston Churchill. By forcing through the abolition of Resale Price Maintenance he cleared the way for the all-conquering march of the supermarket and transformed every high street in the country. By securing Britain’s entry into Europe he reversed almost a thousand years of history and embarked on a course that would inevitably lead to the legal, political, economic and social transformation of his country. Both these reforms he forced through by a combination of determination, patience and persuasive powers, against the inertia or active hostility of a large part of the British population, including many of his own party. There may have been others who could have done as much, there may have been others who desired to do so, but it is hard to conceive of any other individual in the second half of the twentieth century who would both have been able and have wished to achieve this transformation.

Yet Heath today is largely forgotten: a meaner beauty of the night eclipsed by the refulgent moon of Margaret Thatcher. This is because, in spite of all he did, he was seen by others, indeed portrayed himself, as a disgruntled loser. Lady Thatcher, though she too was shipwrecked in the end, is remembered as a winner. It is the winners who remain prominent in people’s minds. Heath brought it on himself, but the importance of his contribution to British history deserves greater attention. Opinions may differ as to whether what he did was right; the immensity of his achievement in doing it is open to no question.

ONE The Child and the Boy

Two future British prime ministers were born in 1916. Both belonged to what may loosely be called the lower-middle class and found their way by scholarships to grammar school and Oxford, where both were strikingly successful. Both served at one time in the civil service and took a precocious interest in politics. Both prided themselves on their knowledge of economics and were endowed by nature with prodigious memories. One was prime minister from October 1964 to June 1970 and from February 1974 to March 1976; the other occupied 10 Downing Street for the intervening years. In all other ways, few men can have been less similar than Harold Wilson and Edward Richard George Heath.

In fact, for those who take an interest in such arcane distinctions, the Wilsons were in origin slightly grander – or at least less humble – than the Heaths. They had been lower-middle class for several generations; the Heaths had only recently taken their first steps from the working classes. Ted Heath’s first identifiable ancestor, his four times great-grandfather, Richard, had been a fisherman living in Cockington in Devonshire at the end of the eighteenth century. His son William followed the same calling but with scant success. By 1819, when William was 56 and presumably too old for an active seafaring life, he found himself with fourteen children and no job and was forced to lodge a petition with Trinity House as having ‘no property or income whatever’. Undiscomfited, his son, Richard, also took to the sea, joined the Coastguard Service and, in 1831, was transferred to the new coastguard station in Ramsgate, Kent. Before migrating he had married a Somerset girl. Their son, George, Ted’s great-grandfather, was the last of the seafaring Heaths; he served with the merchant navy and ended his working days in charge of Ramsgate pier. 1

George married a local girl. Their son, Stephen, the first terrestrial Heath, did not notably improve the family’s prosperity. He went into the dairy business and at first did well, but then, according to his son William, ‘lost all his money and went on the railway’, 2with the unglamorous task of moving passengers’ luggage between the station and the hotels. He survived this setback with equanimity and lived to the age of seventy-seven, invariably genial, frequently inebriated and loved by his grandson, Ted. He too married a Kentish girl, as did William, Ted’s father. Ted, therefore, was of solidly Devonshire and Kentish stock, with no tincture of more exotic blood in the five generations before his birth. In 1962 Iain Macleod, seeking Heath’s endorsement when a candidate for the Rectorship of Glasgow University, asked hopefully whether he could not scrape up some Scottish connection, however tenuous. His only claim, Heath replied, was that he had been educated at Balliol, a college which owed its existence to John de Balliol and Dervorguilla of Galway: ‘I do not know whether on this somewhat flimsy basis you will be able to build up a case which will secure the Nationalist vote.’ 3

William Heath was far more like his exuberant and outgoing father than his more unapproachable son. He was a ‘quiet and unassuming’ man, said Heath in his memoirs, 4but this does not correspond with the testimony of many of those who knew him well. He was ‘a dear man’, said Nancy-Joan Seligman; ‘heaven’, said Mary Lou de Zulueta; ‘a great hugger and kisser, even a bottom-pincher, to the occasional embarrassment of his son’, recalled Margaret Chadd. 5He loved parties: other people’s would do but it was best of all to be at the centre of his own. His jollity was not allowed to interfere with his work, however: he was enterprising, energetic and conscientious. By training he was a carpenter; he ended up as a builder with his own firm, small but still employing several workmen. Ted Heath took considerable pride in his father’s advance into the middle classes. In his biography, John Campbell mentioned that Heath had had to be dissuaded from suing

Читать дальше