Philippa Langley and Michael Jones

THE KING’S GRAVE

The Discovery of Richard III’s Lost Burial Place and the Clues It Holds

To all those who saved the Dig, and to all those whose researches have illuminated Richard III as man and king

Billsdon: Medieval plan of Leicester

Greyfriars area including car parks

Thomas Roberts’s map of 1741

Bosworth: the approach to battle

The Battle of Bosworth: the final phase

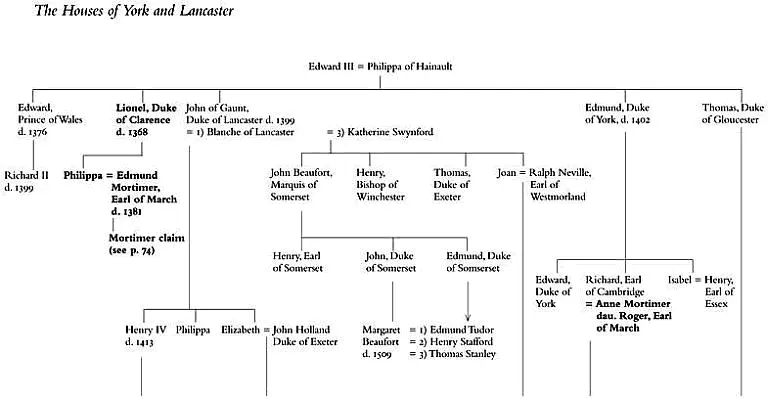

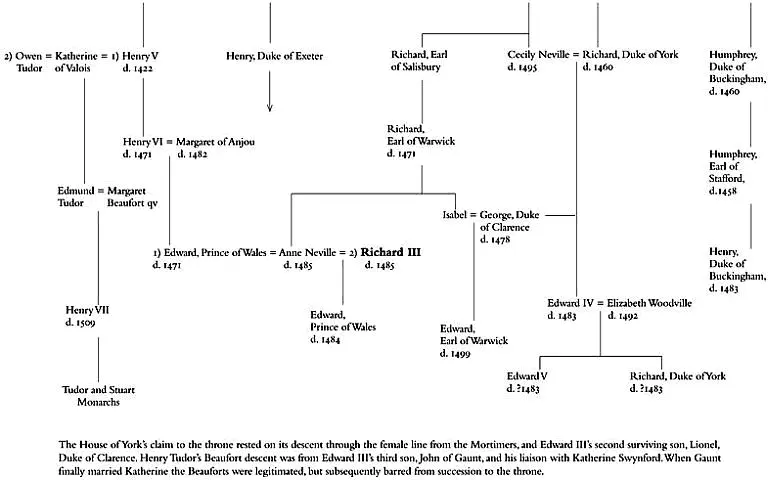

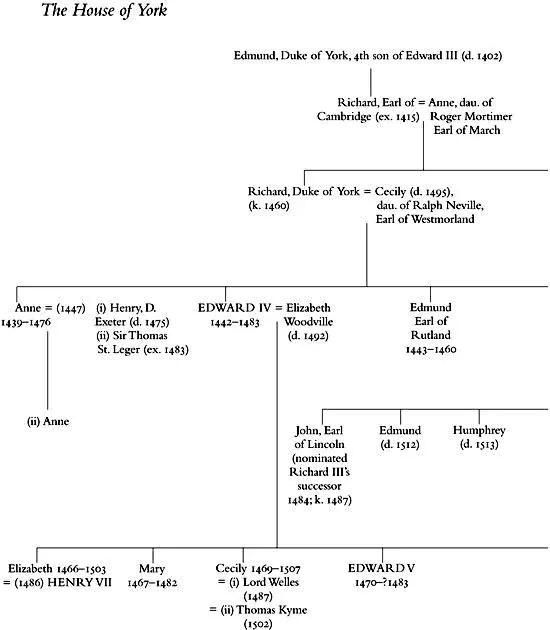

ON 22 AUGUST 1485 two armies faced each other at Bosworth Field in Leicestershire. King Richard III, of the House of York, lined up in battle against his rival to the throne, Henry Tudor – a clash of arms that would determine the fate of England. It was Tudor who won the victory. Richard was cut down after leading a cavalry charge against his opponent and killed in savage fighting, after being only a few feet away from Henry himself. He was the last English king to die in battle.

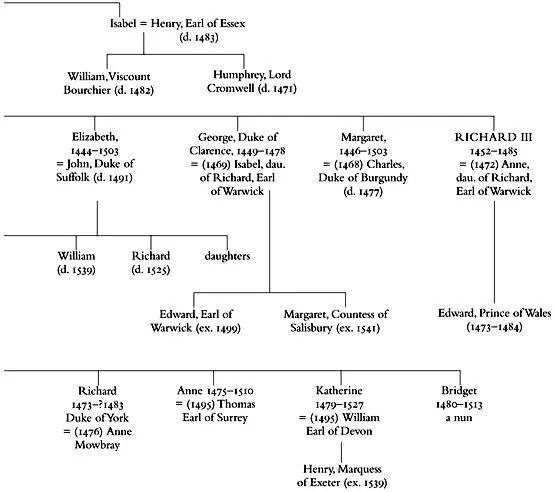

That year marks a pivotal date in our history books: the ending of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the modern era. The House of Tudor became one of our most famous ruling dynasties – and its 118-year triumph culminated with William Shakespeare’s history plays. Within them, Richard III emerged as one of England’s most consummate and appalling villains, a ruthless plotter, an outcast from his own family, deformed in body and nature, who murdered his way to the throne. The most horrifying of these crimes was the killing of the young nephews placed in his care, the Princes in the Tower. In Shakespeare’s Richard III, the king’s own death at Bosworth is powerfully portrayed – alone, with no means of escape and surrounded by his enemies, Richard calls out: ‘A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!’ His despairing cry is not heeded and he is overpowered and slain. It is the judgement of God upon his wickedness.

Shakespeare’s drama was based on a series of Tudor histories that progressively blackened Richard’s name. The principal charge against him in the reign of Henry VII was that he had seized the throne by killing his nephews. That ghastly accusation – believed by many – should have been enough to consign him to the scrapheap of history. But by the reign of Henry VIII he had already been accused of a number of additional crimes, including disposing of his brother, George, Duke of Clarence, in the most startling fashion, drowning him in a large vat of malmsey wine. By the reign of Elizabeth I it was commonly believed that he had poisoned his own wife. It is striking how the Tudors kept adding to Richard’s tally of victims. Alongside this was an almost compulsive need to distort his appearance. A physical characteristic, where one shoulder was raised higher than the other, was deliberately exaggerated in a succession of Tudor portraits to depict the king in increasingly sinister fashion.

By the time of Shakespeare this propaganda had reached its zenith. Richard had now become a crouching hunchback, whose bent and distorted body mirrored the hideous depravity of his crimes. By then, the king’s actual body, buried hastily in Leicester in the aftermath of the Battle of Bosworth, had disappeared from view. It was widely believed that the disgraced monarch’s humble grave, in the Church of the Greyfriars, had been lost at the time of Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries – its contents even emptied into the River Soar. With the king’s remains seemingly absent, the Tudors further twisted his historical reputation. He grew into a dark Machiavellian figure, an outcast from all sensibility – whose life and death provided a terrible moral warning.

It was a damning indictment – yet some were suspicious. Early in the reign of James I a number of attempts were made to present an alternative, redeeming portrait of the vilified king. Such efforts have persisted to this day, with the founding of the Richard III Society, determined to present a more human and sympathetic picture of Richard as man and monarch. More recent academic studies have modified the Tudor legend in some respects. Yet, despite all these efforts, Shakespeare created a play so sinister and darkly seductive that it still remains the portrait most are drawn to. Shakespeare’s powerful and unsettling depiction, of a man beyond the moral pale, gained new currency when it was transformed into the Sir Laurence Olivier film in 1955. It has been long recognized that only a discovery as important as Shakespeare’s drama is compelling would provide a counterpoint to the Tudor villain the playwright portrayed. Now – in a municipal car park in Leicester – that discovery has been made. The grave of Richard III has been found – with the king’s body still within it. It is one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of recent history.

This book reveals the remarkable series of events that led to this astonishing find. It tells of a search for Richard’s remains – and also, accompanying it, the search for his real historical reputation. For, before the remnants of his body were uncovered, permission was obtained by Philippa Langley for them to be laid to rest – in a proper and fitting reburial – in Leicester Cathedral. Here at last was an opportunity to step beyond Shakespeare and make peace with the most vilified of our rulers. Not to condemn him, nor to sanitize his actions, but to place him firmly back in the context of his times.

As Richard’s bones were painstakingly examined, it was found that he had scoliosis, a curvature of the spine that would have left one shoulder higher than the other. It also quickly became apparent that his body was racked with battle injuries. A time capsule had been opened, showing the last moments of Richard’s bloody fight at Bosworth: the king’s head shaved by the glancing blows from a halberd or sword, the back of his skull completely cleaved off by a halberd – a two-handed pole weapon, consisting of an axe blade tipped in a spike. And then, as his face was powerfully reconstructed from the skeletal structure around it, we at last had the opportunity to see him as he really was.

This is the story of one of history’s most infamous kings – now restored to us – and the man behind the Tudor myth.

Philippa Langley and Michael Jones July 2013

Chronology of Richard’s Life

2 October 1452

Richard born at Fotheringhay, Northamptonshire

12 October 1459

Richard’s father goes into exile after his defeat at Ludford

30 December 1460

Battle of Wakefield. Richard’s father and brother Edmund killed

2 February 1461

Battle of Mortimer’s Cross. Richard’s oldest brother, Edward, Earl of March, victorious against the Lancastrians

Читать дальше