The Duke of Fragnito had similar preconceptions when he met the duchess in Palm Beach in the early 1960s. ‘I didn’t want to like her because of everything I had heard about her,’ he admitted. ‘But I was taken aback by her grace and impeccable manners. To my great surprise she behaved like a real royal. She was just as captivating as the duke. They both had this ability to produce an electric charm which I have never forgotten.’

Vogue editor Diana Vreeland noted of Wallis: ‘There was something about her that made you look twice.’ The duchess’s private secretary, Joanna Schutz, accompanied Wallis to New York by boat shortly after the duke died. The duchess did not put her name on the passenger list and usually ate in her room. Occasionally, she would enter the dining room to keep Miss Schutz company. ‘Some people recognised her, others didn’t, but they knew she was special,’ said Hugo Vickers. ‘She was somebody. She had a hypnotic effect.’

‘I can’t say that she was sexy but she was sassy,’ remembered Nicky Haslam. ‘She walked into the room and it took off. The only other person I knew who had that quality was Frank Sinatra.’ Haslam, an interior designer who met Wallis in New York in 1962, said: ‘Wallis had innate American style. But to be an American was against her then, almost more than the divorce.’ Wallis described the archaic snobbery she encountered when living in London: ‘The British seemed to cherish a sentiment of settled disapproval towards things American.’

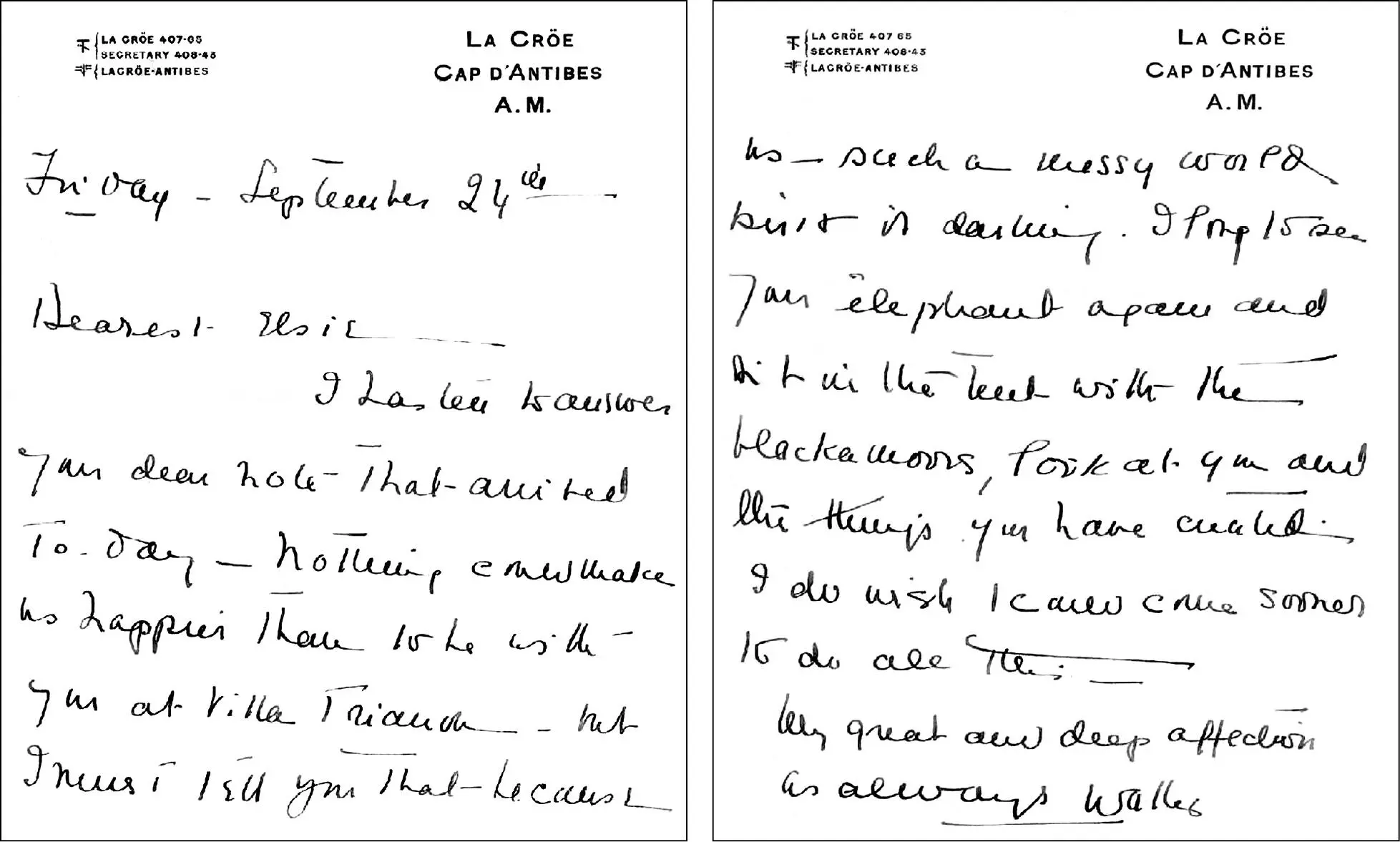

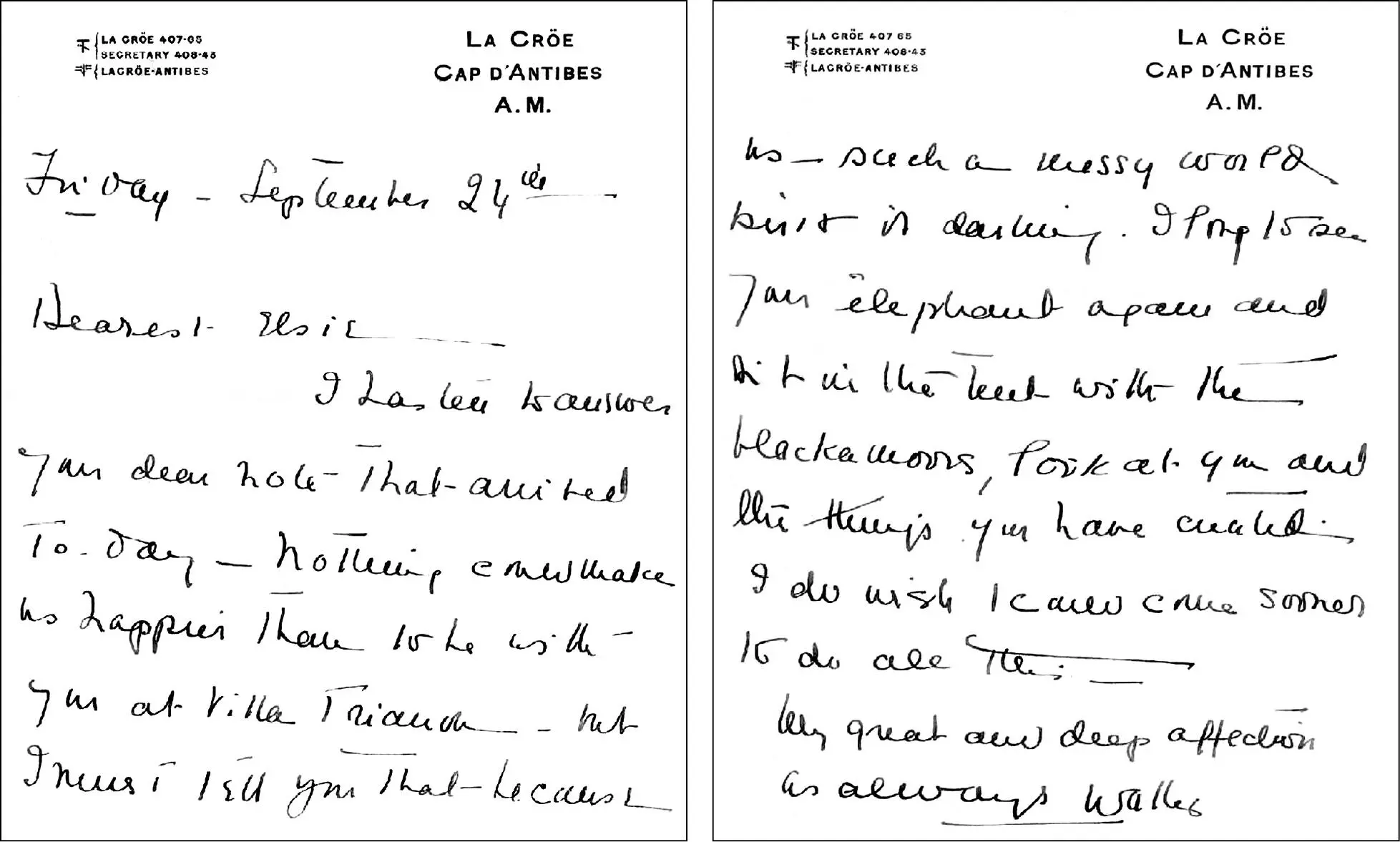

I was sitting with Nicholas Haslam in a Chelsea restaurant, when he produced an envelope, saying that he had something special to show me. It was a handwritten letter from Wallis to her friend, Elsie de Wolfe. Elsie, who became Lady Mendl in 1926 on her marriage to Sir Charles Mendl, a press attaché to the British embassy in Paris, was an eccentric who practised yoga and underwent plastic surgeries, years before both became de rigueur. Credited with inventing the profession of interior decorating, she was famed for her elaborate parties, and in particular the Circus Ball at the Villa Trianon, in Versailles in 1939. Attended by over 700 guests, including the duke and duchess, the ball was held in a green and white dance pavilion, and featured a fabulously jewelled elephant. Circumstances would force Wallis to adopt Elsie’s favourite motto, embroidered on taffeta cushions strewn throughout the Villa Trianon: ‘Never Complain, Never Explain’.

Turning the letter over in my hand, I admired Wallis’s chic stationery, the thick envelope lined with forest green tissue paper and the simple address on crisp cream paper, ‘La Croë, Cap D’Antibes’, the duke and duchess’s villa in the south of France. The letter, written in 1948, and dated Friday 24 September, reveals Wallis’s loose, looping handwriting in black ink: open and hurried in style and pace, there are endearing crossings out and insertions as her thoughts race across the page with barely any punctuation. She asks Elsie if she and Edward can come to stay with her at the Villa Trianon on their way back to Paris, and shares details of her day-to-day life: ‘I swam this A.M and tonight I go to Cap d’ail to play Oklahoma [a card game] with Winston Churchill who is stopping with Max Beaverbrook – we are great rivals and play every other night …’

The letter is full of warmth and love. Wallis reveals herself to be a genuine, open friend. She tells Elsie how difficult it is packing up and leaving La Croë, which she and the duke had leased for the previous decade. Her loneliness and tension is tangible; she details her desire to be alone, relaxing with Elsie, whom she misses: ‘I long to see your elephant again and sit in the tent with the blackamoors, look at you and the things you have created,’ Wallis wrote. ‘I do wish I could come sooner to do all this. My great and deep affection, as always, Wallis.’

When I contemplated the duke and duchess’s empty, peripatetic life after abdication and exile, I felt a profound sadness. What was their purpose from that point on? To live a life together to prove that it had not all been for nought? To be happy? To appear to be happy? There must have been an element of continuous silent strain for them both, a seam of guilt they dared not plunder. ‘I have a theory that when men let women down, they feel awful,’ Hugo Vickers told me. ‘The duke turned Wallis into the most hated woman in the world, then he couldn’t get her what he promised her: the HRH title, or his family to accept her. So he must have spent his whole life feeling guilty. I saw him once at Princess Marina’s *funeral and I have never seen a man with sadder eyes.’

Over three decades into their post-abdication existence, just a few years before the duke’s death, the Windsors were interviewed on live television, on the BBC, by the broadcaster, Kenneth Harris. The programme was watched by 12 million viewers. Wallis comes across effortlessly, she is witty and warm. The duke, with his hangdog eyes, appears less comfortable in his own skin, constantly looking down at his hands, studying his nails, fidgeting. The interviewer asks the couple if they have any regrets. The duchess, elegant in cream silk with a pale blue scarf, laughs nervously: ‘About certain things. I wish it could have been different. Naturally, we’ve had some hard times. Who hasn’t? But we’ve been very happy.’ The duke awkwardly grabs her hand in confirmation.

The main aim of this book is to look beneath this convenient illusion and give Wallis a voice: to peel back the layers of prejudice and examine the wider motives for the enduring propaganda against her. For Edward the relationship started as a thrilling coup de foudre ; for Wallis, it would soon feel like a Faustian pact. Did a genuine love emerge between them as they surmounted the abdication together; or was the monumental sacrifice on both their parts a tragedy of Shakespearean proportions? Wallis, quietly stoical, rarely sought pity or openly complained about her suffering. She was always incredibly dignified, generously concluding in her memoirs: ‘Any woman who has been loved as I have been loved, and who, too, has loved, has experienced life in its fullness.’

*Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent (1906–68), was born Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark. She was married to Prince George, Duke of Kent, Edward’s favourite brother.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.