There are no crossings-out or hesitations. Once or twice the ink fades abruptly in the middle of a word, in the space of a few letters. But the writer must have spare cartridges close by, because instantly it spurts away again, hauling the day on.

Life is an emptiness in these late books. All talk about the Great Project is gone. There is no mention of ‘it’. He sees nobody and goes nowhere. ‘I’ describes himself as ‘ruined’, lost’, ‘sacrificed’. There has been a smash of all his hopes. It is not only the man called Peter who is responsible for this catastrophe; ‘I’ several times accuses ‘those who are stuffed with sleep’.

The writer refers to this man called Peter as his ‘gaoler’ – a ‘cruel’ person.

I just wish I could put my hands round his throat

and strangle him – throttle him to death.

We never see Peter. The writer never describes him physically. We smell him. ‘Pongy Peter’, ‘I’ labels him; ‘Stinky Peter’. Occasionally, particularly at night, we hear him. His footsteps creak along the corridor below; there is a rattle at the rear of the house and a rush of water: he has gone to the toilet.

It is still a riddle to me, how all the stink of his wicklery [going to the toilet] comes up to the back landing when he has a crap – if it comes up through the drainpipes or the ventilators or what. Or if the smell seeps out of his bedroom from the pipe to his washbasin.

Occasionally, Peter creeps into ‘I’s room. What happens next is hardly believable. He steals ‘I’s belongings! Books, valuable letters, volumes of the diaries themselves. He sets light to his haul in the garden.

I think Peter must have burnt all E’s photos, and a lot of the music – took advantage when I was in hospital.

What is going on? Why doesn’t the diarist stop this hateful behaviour?

Peter is a detestable man.

He seems indestructible, like Nelson Mandela.

May just look back on a life of struggle, at the age of sixty or so – and feel deeply sad, because in spite of various talents, of great beauty, have come to nothing.

Aged twenty-one

Six of the diaries in the thigh box are ‘Max-Val’ exercise books, stapled along the centre-fold, with paper made out of oat biscuits. The colour of these dreary little volumes is washed-out, Latin-class blue. Printed on the back of each is a set of Arithmetical Tables giving the lengths for cloth measure (2½ inches = 1 nail), the amount of grass needed to make up a ‘Truss’ (56lbs of Old Hay; 60lbs, New Hay; 36lbs of Straw), and, my favourite, ‘Apothecaries’ Weight for mixing medicines’: 20 grains = 1 Scruple.

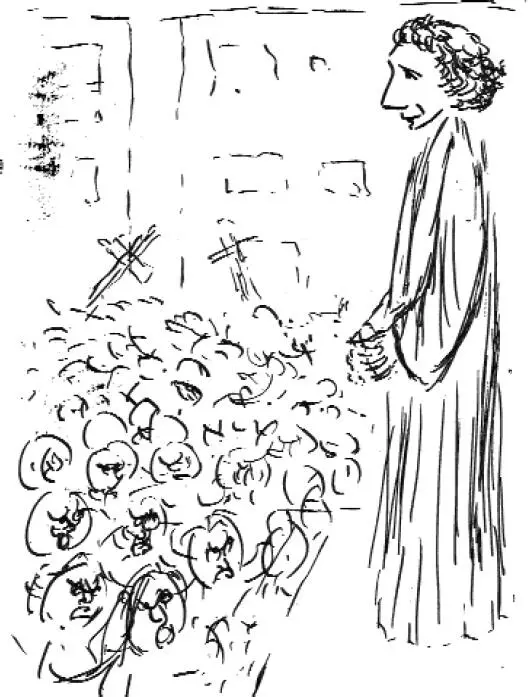

Inside the books is a rapidly hand-drawn cartoon strip in blue ink. There are between two and eight frames per page. Nowadays it would be called a graphic novel. The scenes are of different sizes and always boxed in. The figures in the story are dressed in cloaks and repeatedly caught in moments of persecution or shock. The faces are distorted. But what’s going on is anybody’s guess.

The narrative does not progress obviously; it is like a set of flash photographs taken of a troupe of melodramatic puppets. The only constant figure is an androgynous and rhinoceros-nosed face:

This face is always viewed from the left, angled down, just off the silhouette. It appears in each frame of the cartoon – a total of well over two thousand times – and always produced in the same way, with nine fundamental lines: one for the forehead, two for the big nose, another to make the priggish upper lip, the chin and jaw are produced by a single wiggle that looks vaguely Arabic, a down stroke for a dimple and three quick movements to make up the eye. Hair (sometimes slicked, sometimes dishevelled) is a rush of slashes or curls on top. Most of the time this wig-wearing flatfish of a face doesn’t reflect much. It appears to be a force of creamy benignity. At its most irritating it represents poetic suffering. Sometimes it has a body coming off it, sometimes not. It is repeated so often that you begin to feel ill at the sight of the thing.

The flatface’s name is (usually) Clarence. It can also be called Rhubarb or Porbarb or John.

Sometimes he’s in prison:

with his two cellmates, the ‘Keeper’, who has a jaw like a casserole pot …

… and a rubber-faced monstrosity called Worful:

‘Clarence’ Flatface lives in the past. Sometimes he’s out of clink and down the tavern, being asked difficult maths questions …

“What’s two and two?”

… that he struggles to answer:

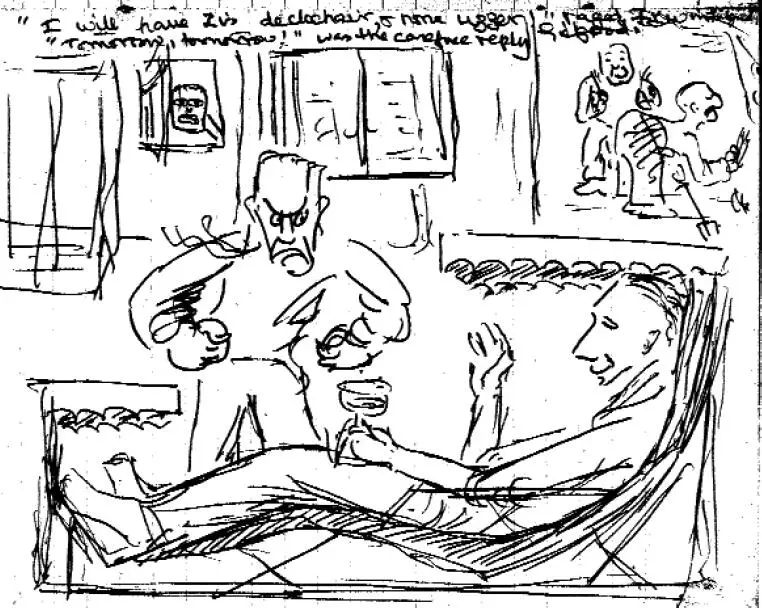

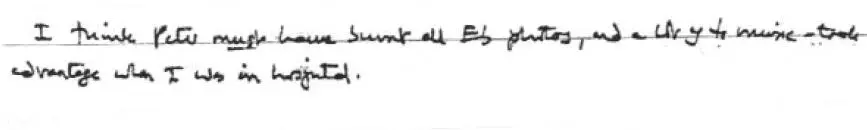

At other times, as ‘John’, Flatface is living at the time the cartoon is being drawn, in the early 1960s. In these contemporary frames ‘John’ might be lying in a fancy deckchair, with a Martini:

“I will have zis deckchair, & none uzzer” raged Irwin.

“Tomorrow, tomorrow!” was the carefree reply.

How did he get into this chair? Why is Irwin (who turns out to be Flatface’s brother) speaking in a German accent? What are those two people up in the air doing – planting carrots? Since when did deckchairs have foot canopies?

Once, as ‘Clarence’, Flatface becomes a king …

… which makes him grumpy.

Another time, Flatface’s days appear to be numbered:

This story never settles down – except for Flatface’s eternal presence. Every fifteen or twenty pages the strip is abruptly cut off and a whole side is given over to this disturbing profile:

Читать дальше

![Никки Сикс - Героиновые дневники. Год из жизни павшей рок-звезды[The Heroin Diaries - A Year in the Life of a Shattered Rock Star]](/books/78612/nikki-siks-geroinovye-dnevniki-god-iz-zhizni-pavshej-rok-zvezdy-the-heroin-diaries-a-yea-thumb.webp)