A few of the volumes had royal emblems embossed on the front:

Others were cheap

exercise pads in stale grey-blue. Many were plain, good-quality hardbacks in old-fashioned, accountancy-office red, stamped with gold letters: ‘Heffers, Cambridge’. Others were thin and black, with illustrated boards that might have been based on neurological patterns, and therefore belonged in a medical lab. There were jotters of the sort 1950s policemen brought out of their breast pockets, and small, plump ledgers that I last remember seeing in my school uniform shop in the 1970s. Some of the books had been partially destroyed by water that had long since dried out. The corners of the paper stuck in blocks; stains of rotting metal seeped into the pages from the staples. A box, big enough to contain a head, had landed further into the skip and split with the impact. Inside were more volumes, with covers ranging from post-war sugar card to glistening, oily hardbacks that looked as though they’d been bought that morning. The box had jaunty green print on the sides: ‘Ribena! 5d off!’

A chalky notebook that Dido picked up broke like chocolate. Inside, the rotted pages were filled with handwriting, right up to the edges, as though the words had been poured in as a fluid.

It was a diary.

All the 148 books in the skip were diaries.

Aged twelve

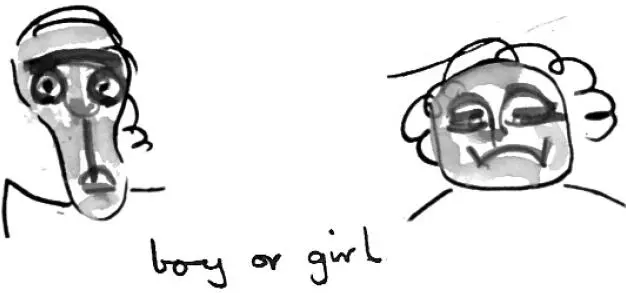

A person can write five million words about itself, and forget to tell you its name.

Or its sex.

People don’t include obvious identifiers in diaries: things such as what they’re called or where their home is. They are simply ‘I’, who lives.

And then dies, and gets dumped in a skip.

It was evident that the author had died. People might burn their intimate diaries before they die, but they don’t throw them out where any stranger can pick them up.

Two terrible things happened after the discovery of the diaries.

Richard was being driven home from a party, in Australia, when the driver fell asleep and crashed the car into a tree. One of the most courageous and inventive academics of his generation, he is still alive, jolting in a wheelchair, and being moved around the nursing homes of England.

Several years later, Dido, my writing collaborator for a quarter of a century, was diagnosed with a ten-centimetre neuroendocrine tumour on her pancreas. I went with her to hear the diagnosis. There aren’t that many times I’ve seen real courage – the sort that makes you start with admiration each time you remember it. Top of my list for biblical chutzpah is Dido’s bemused calm as we came out of the GP’s surgery. ‘Well, I’ve had a nice life,’ she said. ‘Now, shall we go through these pages of yours in Waitrose’s café? It’s cooler there.’

A few weeks later she began to clear out her house. She had not progressed far with discovering who owned the diaries. As well as no name or return address, on the pages inside there were no obvious descriptions of the writer’s appearance, his or her job, or identifiable details of friends or family members. Everything that a person uses to clarify themselves to another person was missing. Why should ‘I’ bother to put them there? ‘I’ knew them already.

What could Dido do with this journal? She couldn’t take it to the police – they’d laugh at her. She couldn’t burn it – that would be criminal.

She gave them to me. It was now my job: I was to find out who was the rightful heir of these ‘living books’, and return them.

She’d put the diaries in three boxes. The original Ribena bottle crate had no lid; one side was caved in and the top half-shut-up, like a punched eye. The last person to touch this box before Dido was the person who’d thrown it out. There was nothing written on the outside except those shouts about ‘5d!’ No packaging label. Nothing with an alternative address. One of the hand holes was ripped clean in half.

The biggest box was thin, plain and approximately the length of a thigh. It bulged meatishly. Through the gaps in the cardboard I could see strips of lurid-coloured modern journals.

The third container was torso-sized and originally for a Canon portable photocopier (‘ZERO warm up time’). It was shiny and strapped down with duct tape. On one edge there was a label, addressed to The Librarian, Trinity College, Cambridge.

Perhaps the diaries belonged to a Trinity don, I thought, and got depressed.

The Ribena box was the one that interested me most.

I imagined the hands of the person who’d pitched it into the skip were still half there, glowing on the cardboard, and wondered if careful scientific analysis could reveal whether the injuries the box had sustained as it landed in the skip were because it had been hurled (perpetrator enraged) or lobbed gently (perpetrator calculating). Using the torch on my mobile phone I peeped through the torn hand hole. The diaries inside had been packed with incompetence. Large dark-coloured journals were separated by single pocket books, leaving narrow shelf-shaped gaps in the layers, like rock caverns. In one corner, a thin hardback had been flattened down with such force that its spine had broken. Many of the books were rotting along the edges, and mossy-coloured, as if I had caught them secretly returning to trees. The cover of one was coated with regular stripes of white mould, like the fungus you get on old cheddar cheese.

I pressed my nose against the hand hole. It smelled crisp and mournful.

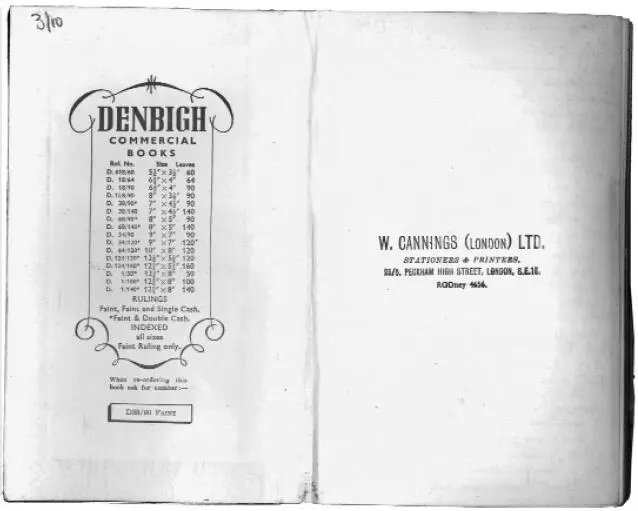

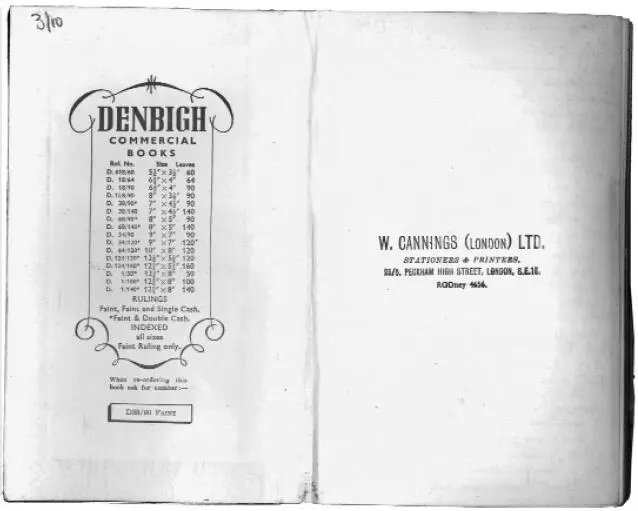

There were twenty-seven diaries in this box in total. The first I picked out was a pocketbook: quarter-bound, blue, with a red spine. Inside, a printer’s advertisement read ‘Denbigh Commercial Books’ in a border made of moustache shapes, which made me think of signs swinging in a mid-western breeze and Clint Eastwood clinking into town. On the facing page, the seller had stamped his details in purple ink: ‘W. Cannings Ltd, 23/5 Peckham High Street, London’. The price was marked in the top left-hand corner, handwritten in pencil: 3/10.

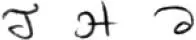

Inside, the pages were crammed to the brim with handwriting. The letters were confident and generous, occupied all the available space on a page with six words to a line, and apart from occasional merriments in the letters ‘J’, ‘H’ and ‘d’,

the script continued with almost mechanical regularity from the front cover to the back. It was not a purpose-made journal. No printed diary could have been manufactured to accommodate this writer’s need. Some entries were four thousand words long; a few were even longer; no day was left alone. It was an ordinary pocket notebook, ambushed by a person’s desperation to record his or her life. At the top of the first page, written inside square brackets, as though it hardly mattered, was the year: 1960.

Читать дальше

![Никки Сикс - Героиновые дневники. Год из жизни павшей рок-звезды[The Heroin Diaries - A Year in the Life of a Shattered Rock Star]](/books/78612/nikki-siks-geroinovye-dnevniki-god-iz-zhizni-pavshej-rok-zvezdy-the-heroin-diaries-a-yea-thumb.webp)