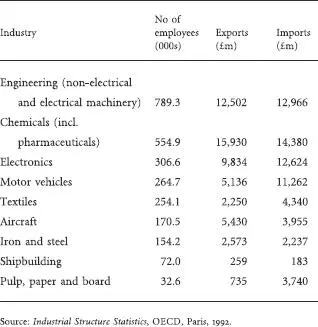

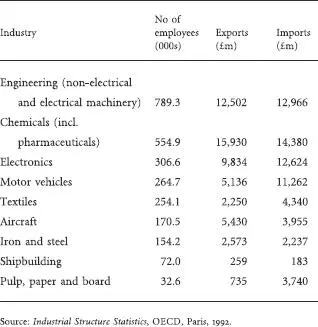

TABLE 1.2 The case study industries in 1988

PART I

TWO

The Consequences of Coming First

There is a widely held view that British industrial decline began in the closing decades of the nineteenth century and has continued remorselessly ever since. According to this account, British entrepreneurs, having led the world in the first industrial revolution, failed to adapt to competition from the two late-industrialising countries, Germany and the US. British industry was locked into a set of institutions and management practices which had become obsolete. The financial system was not well organised to supply risk capital for the new industries of the second industrial revolution; the education system did not produce enough scientists and engineers; and the labour relations system slowed down the introduction of new manufacturing methods.

It is certainly true that Britain was caught up by the US and Germany between 1870 and 1914. It is also true that the institutions and capabilities which the two late-comers developed were different from those on which the British industrial revolution had been based. One well-known example is the emergence in Germany of the big universal banks, led by Deutsche Bank, which made long-term loans to their industrial clients and organised stock market flotations for them, while British banks concentrated almost entirely on short-term lending. Another is the creation in the US towards the end of the nineteenth century of large, professionally managed corporations, while British businessmen still clung to what Alfred Chandler, the American business historian, has called personal capitalism – a structure of small, family-controlled firms, lacking the economies of scale enjoyed by their US counterparts. 1

A much-debated issue is whether Britain’s inability to match these and other innovations constitutes an entrepreneurial failure, and, if so, whether the failure was sufficiently serious and long-lasting to be relevant to what happened after 1945. Was it a disadvantage to have come first?

The Growth of British Industry from 1750 to 1870

Britain’s industrial revolution, which began in the second half of the eighteenth century, was driven by technological change in three sectors. The pace-setter was cotton textiles. The substitution of machines for human effort in the spinning and weaving of cotton generated a huge domestic and international demand for a fabric which had previously been too expensive to capture a mass market. Second, new iron-making techniques – the replacement of charcoal by coke in the smelting of iron ore and the ‘puddling’ process for refining pig iron – increased the supply and lowered the price of wrought iron, which became the building block of the industrial revolution. 2The third breakthrough was the steam engine, first used for pumping water out of coal-mines and later replacing water power in driving machinery of all kinds.

Why did this burst of technological progress occur in Britain and not elsewhere? France was arguably a richer economy at the start of the eighteenth century and more advanced in science. But Britain had several advantages which, taken together, made the industrial revolution possible. 3One was an ample supply of cheap and accessible coal. Another was an endowment of mechanical skills which had been built up in old-established trades such as clock-making and the manufacture of ship’s instruments. The great inventors and engineers of the industrial revolution were predominantly craftsmen, trained in the workshop, and their skills were practical rather than theoretical. Some of them worked closely with scientists, and their lack of formal education did not preclude ‘a rational faith in the orderliness and predictability of natural phenomena, even if the actual laws underlying physics and chemistry were not fully understood.’ 4To describe them as tinkerers hardly does justice to their achievements, but they relied on experience and intuition, not on scientific knowledge.

The initial stimulus for exploiting these innovations came from domestic demand. Although society was organised hierarchically with the aristocrats at the top and the labouring poor at the bottom, differences in spending patterns were less extreme than in other parts of Europe. Britain was also a more unified economy than its European neighbours, with an efficient transport system, so that regions could specialise in particular industries, as Lancashire did in cotton textiles, and serve a national market.

The provision of education for the mass of the population was poor, but the technologies which were being introduced did not depend on a highly educated labour force. Most of the necessary skills could be learned on the job. Where craftsmanship was called for, as in the metal-working industries, apprenticeship was the principal means of acquiring and transmitting skills. This system, adapted from the medieval guilds, suited employers because it was a cheap and efficient form of training which could be administered largely by the craftsmen themselves. It suited the craftsmen because it preserved their status as a highly paid group set apart from the growing mass of semi-skilled and unskilled workers. A distinctive feature of factory organisation in the first phase of the industrial revolution was the use of skilled workers as ‘internal contractors’, responsible for organising the work of less skilled employees. 5

The political and economic environment was highly conducive to entrepreneurship and the pursuit of wealth. Since the Glorious Revolution of 1688 Britain had been a peaceful, orderly society. The old conflicts between King and Parliament been resolved without the upheaval which engulfed France at the end of the eighteenth century. The King could not borrow or tax without the consent of the country’s wealth-holders, and, unlike France, Britain developed financial institutions which provided a secure basis for private commercial activity. 6The ruling élite was a landowning aristocracy which, far from resisting industrialisation, saw it as an opportunity for making themselves richer. Although the landowners were rarely entrepreneurs in their own right, they supported new businesses with patronage and money, and were eager to exploit the coal and iron ore that lay under their estates. Success in business was seen as a way in which ‘middling’ people from non-aristocratic backgrounds could lift themselves into a higher social category. A business career was particularly attractive for religious dissenters who were barred from politics and public service. But while this group supplied a large number of well-known industrialists, there was no special merit in being an outsider. Entrepreneurial talent came from a variety of sources, including foreign immigrants as well as the younger sons of the aristocracy.

Industrialisation took place without direction or control from the state. The role of the government was to ensure that no obstacles were put in its way. The authorities maintained public order, guaranteed the security of property, and upheld a legal system which was helpful to entrepreneurs. Laissez-faire was the guiding principle in most areas of public policy well before Adam Smith published his Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations in 1776. The major exception was in overseas trade, where Britain, like other European countries, had been committed since the seventeenth century to mercantilism. Under this doctrine domestic industry was protected by tariffs; trade with the colonies was reserved for British manufacturers and merchants; and the colonies produced only those commodities which the mother country wanted. These arrangements, providing secure markets for British-made goods, were helpful for British manufacturers in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, 7but overseas trade was not the principal driver of the industrial revolution. It was not until the early decades of the nineteenth century that Britain’s leading industries came to depend on exports to maintain their rate of growth.

Читать дальше