What precipitated these changes? Why did they occur in the 1980s, and not thirty years earlier?

During the 1970s a series of shocks – Britain’s entry into the Common Market, the rise of Japan and the newly industrialising countries, the slowdown in the world economy after the first oil crisis – exposed weaknesses in British industry which had been partially obscured and more easily tolerated in the earlier post-war years. By the end of the decade companies such as GKN were forced to take a more critical look at themselves, and decide which of their businesses, if any, could compete on the world stage.

These external pressures coincided with a change in the political climate within Britain. The election of a Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher in May 1979 heralded a break with the past in the management of the economy. A fierce determination to defeat inflation through strict monetary and fiscal policies was combined with a greater emphasis on competition and deregulation. Virtually all the industries which had been nationalised since 1945 – and some, like the telephone network, which had been in government hands for much longer – were transferred to the private sector. The labour relations system, which had been partly responsible for Britain’s reputation as the sick man of Europe, was drastically reformed.

A third ingredient was the phenomenon which came to be known as globalisation. During the 1980s increasing cross-border investment altered the structure of several major industries, paper and cars being two notable examples. Many of the world’s leading companies built or acquired factories in their major markets, and organised their manufacturing and distribution on an international basis. Britain benefited from this process because, thanks to Margaret Thatcher, it had become a more attractive location for investment. The Conservative government was also more relaxed than its predecessors about allowing former ‘national champions’ to be acquired by foreign companies; no objection was raised when BMW bought Rover, or when ICL, the computer manufacturer, was sold to Fujitsu of Japan.

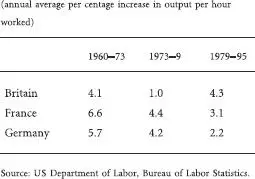

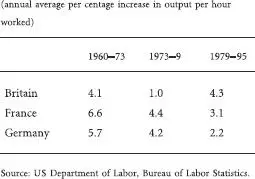

The combined effect of international competition, domestic policy reform and foreign investment brought to an end a long period in which productivity in British manufacturing had grown more slowly than in other European countries (TABLE 1.1). After years of falling behind, Britain was catching up.

This book describes how the transition came about. It focuses on firms and the people who ran them, and on the domestic and international environment in which they were operating. The aim is to identify the reasons for Britain’s poor industrial performance, compared to other European countries, in the first thirty years after the war, and to assess the significance of the changes that occurred in the 1980s and 1990s.

TABLE 1.1 Labour productivity in manufacturing 1960–95

What firms can do in international competition is constrained by the economics of the industry they are competing in and by the conditions which they face in their home base: countries provide a better ‘global platform’ for some industries than for others. 3In some cases companies may derive a competitive advantage from the size and character of domestic demand for their products. In others the crucial factor may be ease of access to essential raw materials. But the most important influence on the international competitiveness of companies, especially in manufacturing, is the extent to which they are helped or hindered by national institutions and policies. To take one example, the US has developed since the Second World War a large and sophisticated community of venture capitalists, who have supported the growth of start-up firms in high-technology industries such as electronics and biotechnology. While access to venture capital is not the only reason for the success of American companies in these industries, it is an institutional asset which other countries do not possess.

Institutions and policies have been central to the long-running controversy about British industrial decline. Three culprits which have figured prominently in the debate – the financial system, the training and education system and the labour relations system – are given special attention in this book. The financial system is accused of failing to provide manufacturing companies with the constructive, long-term support which is available in other countries. The education system has been criticised for being too detached from the world of industry, leading to an inadequate supply of technical and managerial skills. The labour relations system is held responsible for the collapse of strike-prone industries such as shipbuilding and cars, and more generally for the slow growth of productivity in British industry as a whole between the 1950s and the 1970s. These institutional weaknesses have been aggravated, some commentators believe, by policy errors on the part of post-war governments. The management of the economy has been erratic, while micro-economic or ‘supply-side’ policies, ranging from nationalisation to the promotion of mergers, have often been ill-considered and counter-productive.

Opinions differ about the relative importance of these factors, and about the extent to which some of the alleged weaknesses – for example, the ‘short-termism’ of British financial markets – continue to put British firms at a disadvantage today. This book seeks to shed light on these issues by making comparisons across countries and across industries. It examines how British firms in a number of major industries responded to international competition after the Second World War, and compares their response with that of their counterparts in other European countries, principally Germany and France; the list of industries covered is set out in TABLE 1.2.

Some British industries did better than others, and the same was true in the two Continental countries. At the end of the 1990s British-owned firms ranked among the world leaders in chemicals and pharmaceuticals, but not in cars. German companies were outstandingly successful in mechanical engineering, but not in computers or television sets. French manufacturers out-performed their British counterparts in cars, but not in machine tools. The purpose of the industry case studies contained in later chapters is to explore the reasons for these national strengths and weaknesses, and thus to illuminate the larger question of how institutions and policies have affected industrial performance.

In studying the interaction between firms, industries and nations, history matters at all three levels. Although the book is primarily concerned with events after 1945, each of the case studies begins by examining the earlier history of the firms and industries concerned. Did British industry enter the post-war period with managerial and technical weaknesses inherited from the past, or was its poor performance after 1945 due to the things that were done or not done in the post-war period itself?

This is a book about British manufacturing, not about the British economy. The focus on manufacturing is not meant to imply that making things is a more important activity than providing services. The proportion of the workforce employed in manufacturing has been declining for many years in Britain, as it has in other industrial countries, and the trend is certain to continue. A nation’s economic strength cannot be considered in terms of manufacturing alone, and some might argue that, by excluding non-manufacturing sectors such as the media and financial services, this book is underplaying the things which British firms are good at. Nevertheless, the post-war history of British manufacturing is a large and complex subject in its own right, and the focus on this part of the economy seems justified in view of the many unresolved controversies which surround it.

Читать дальше