William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2015

Copyright © Raghu Karnad 2015

Raghu Karnad asserts his moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

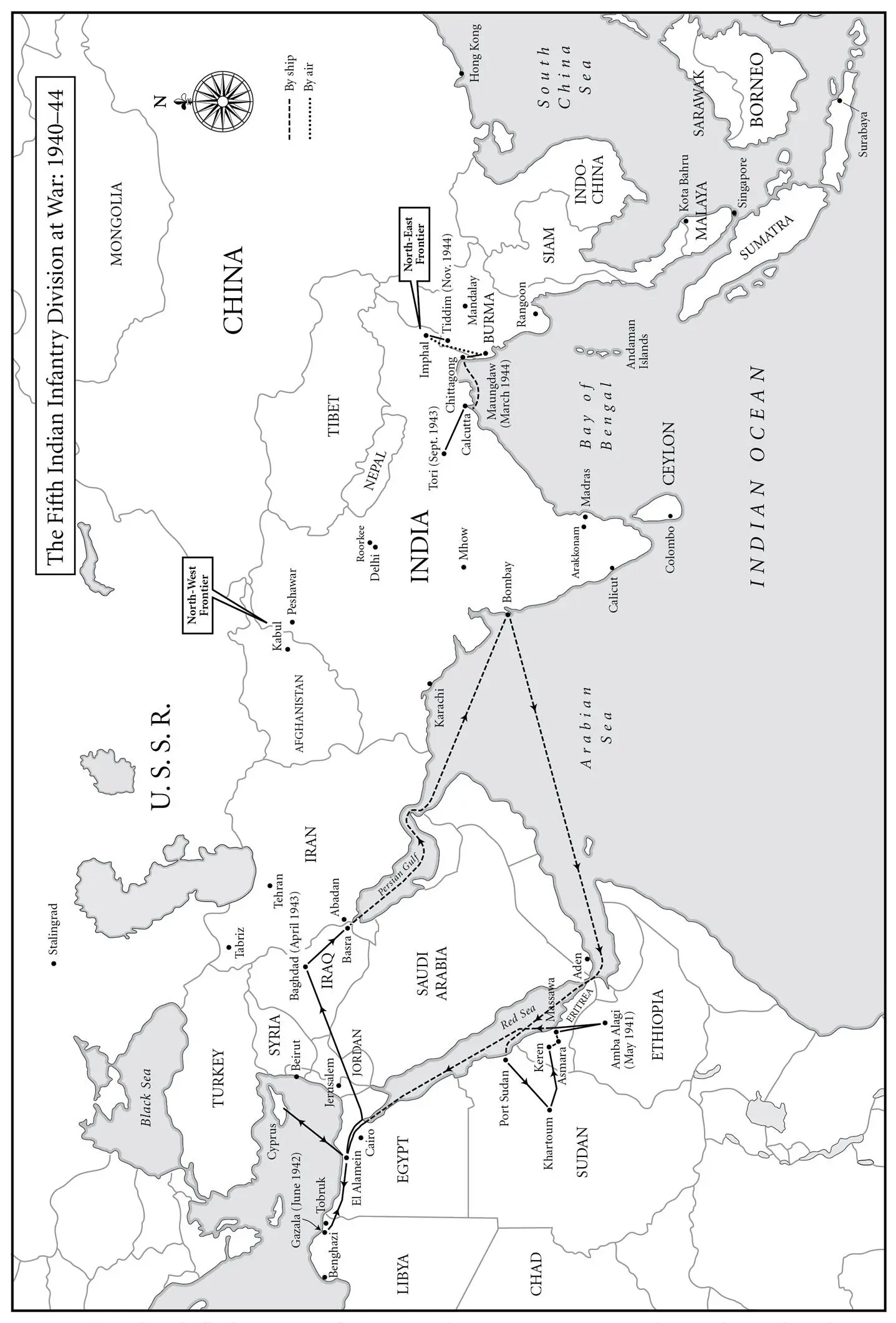

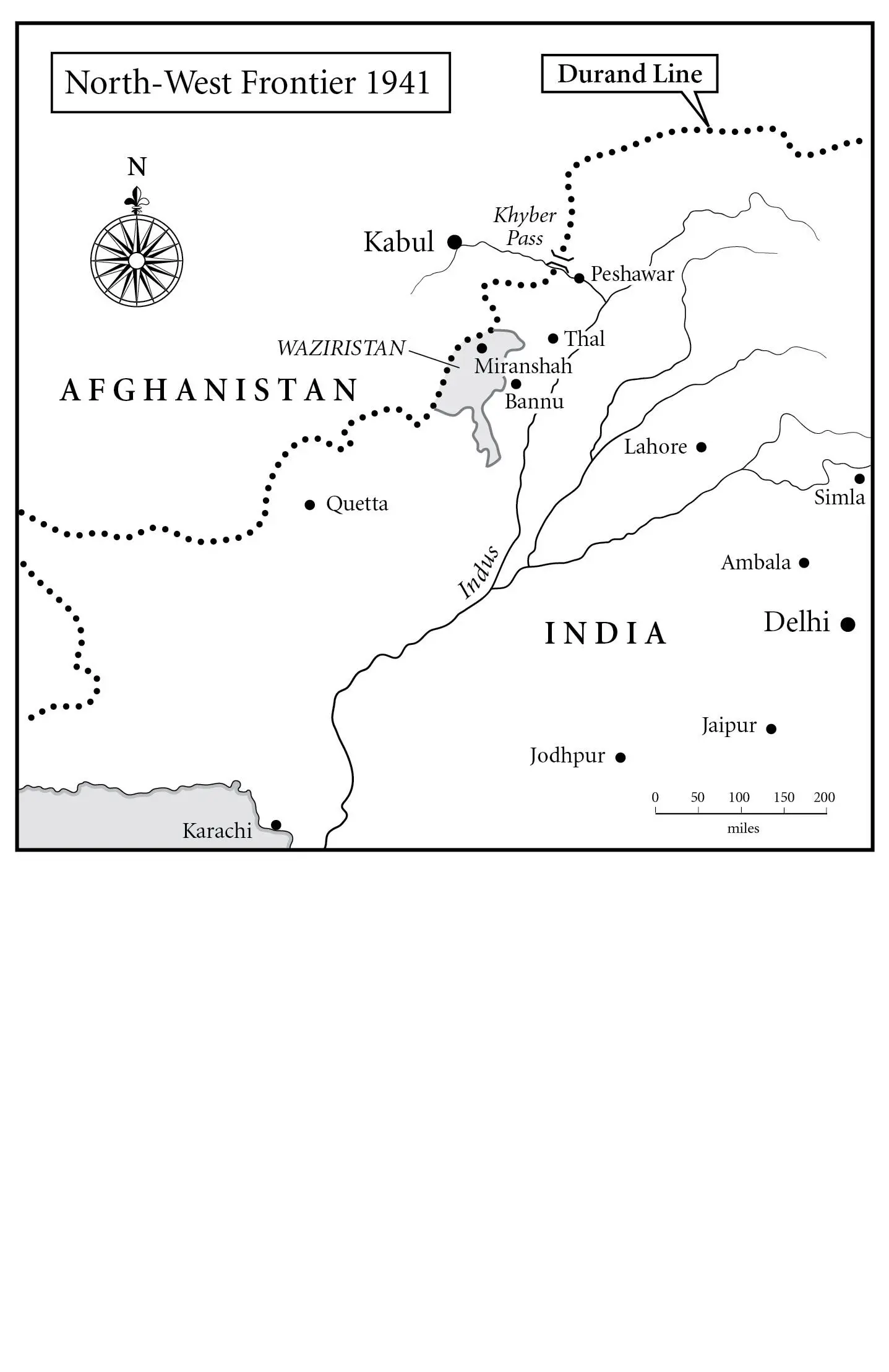

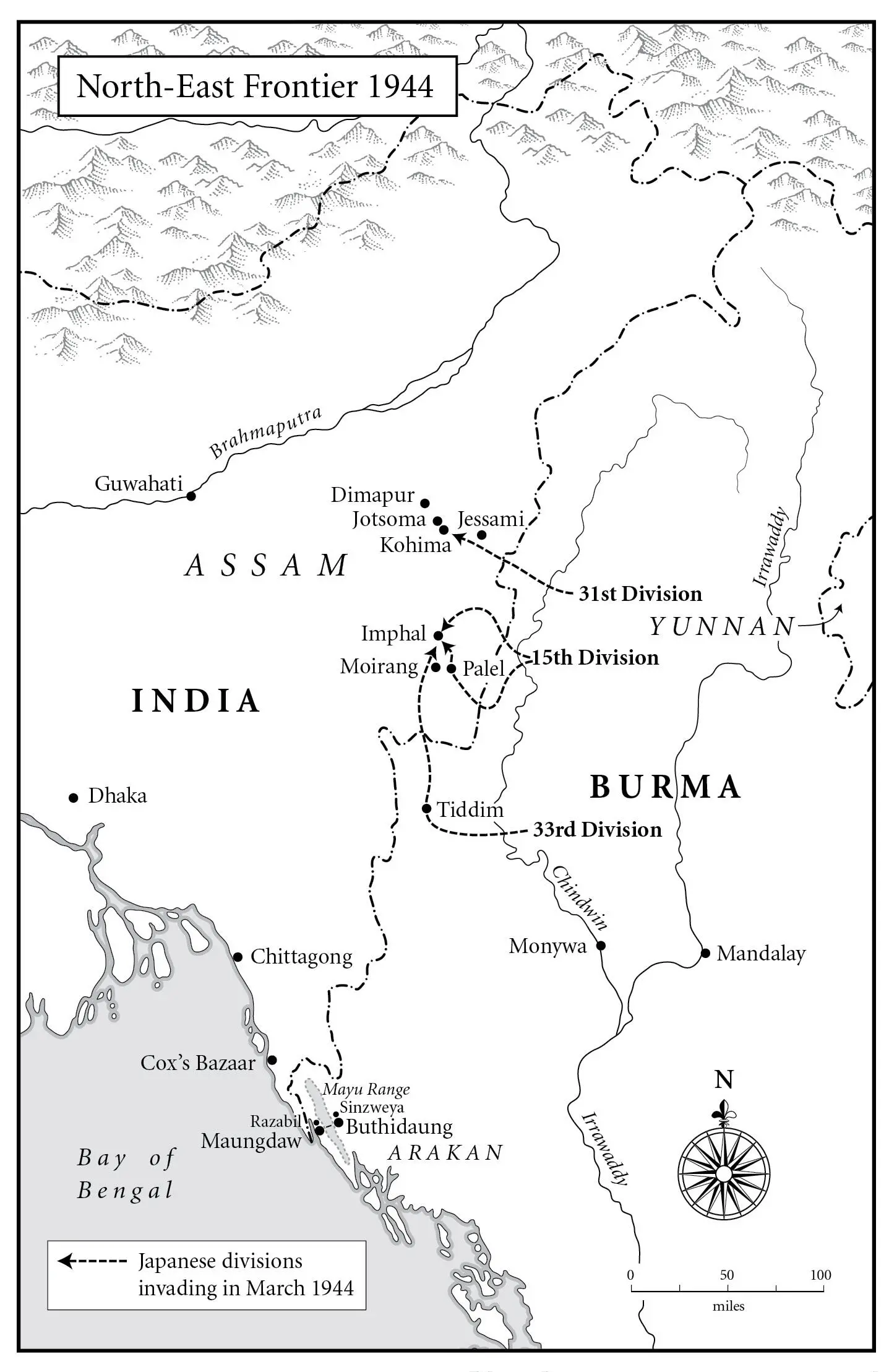

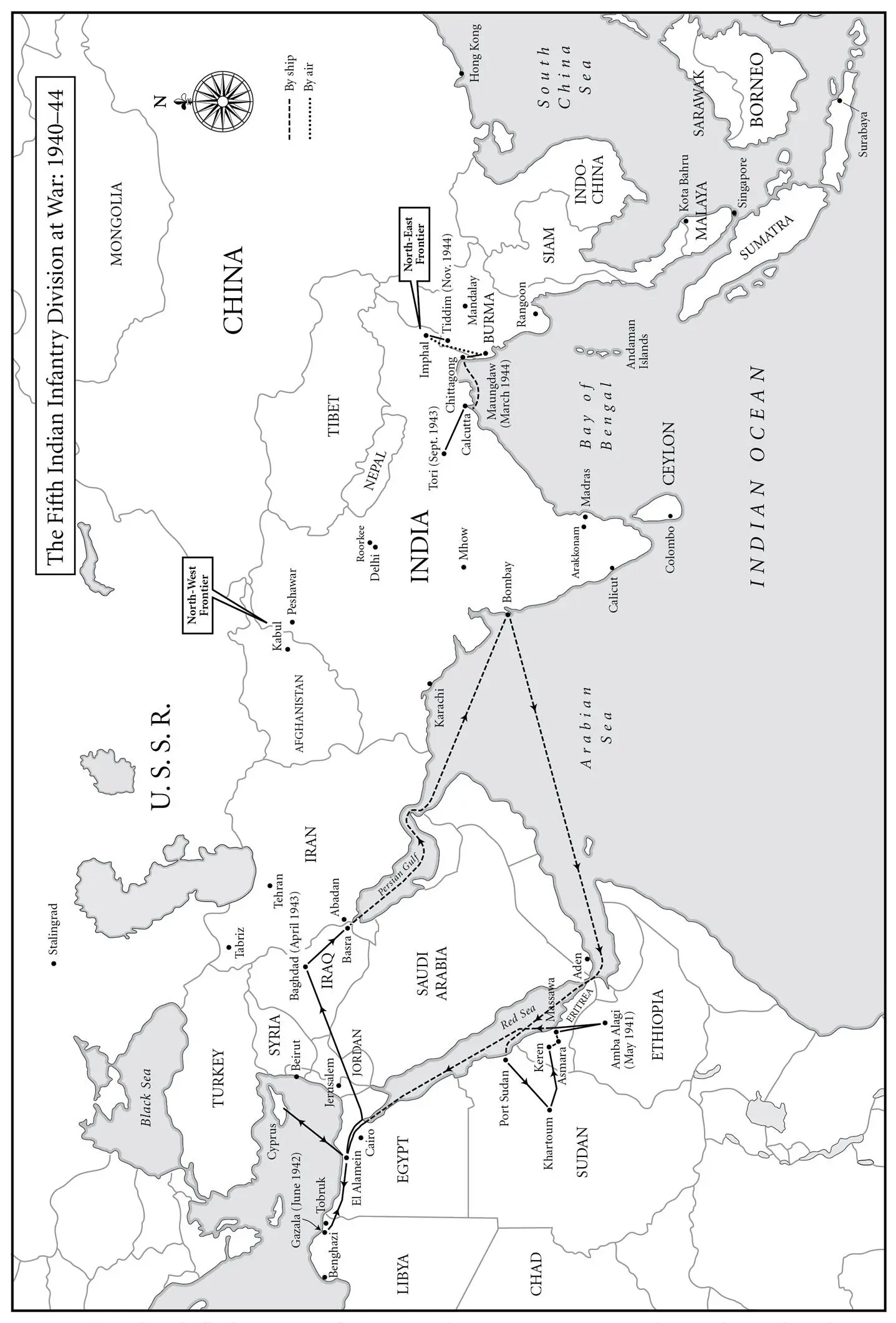

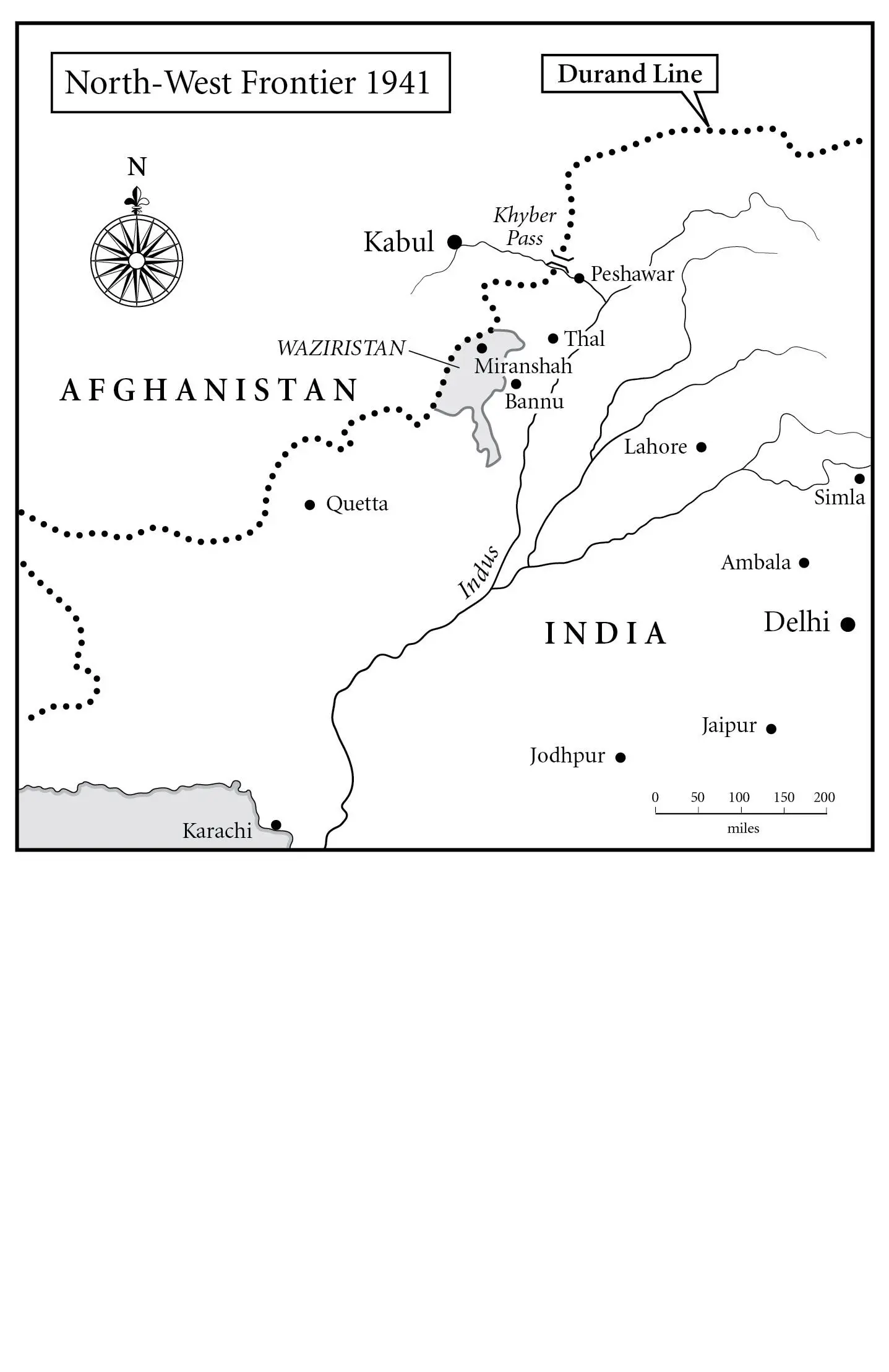

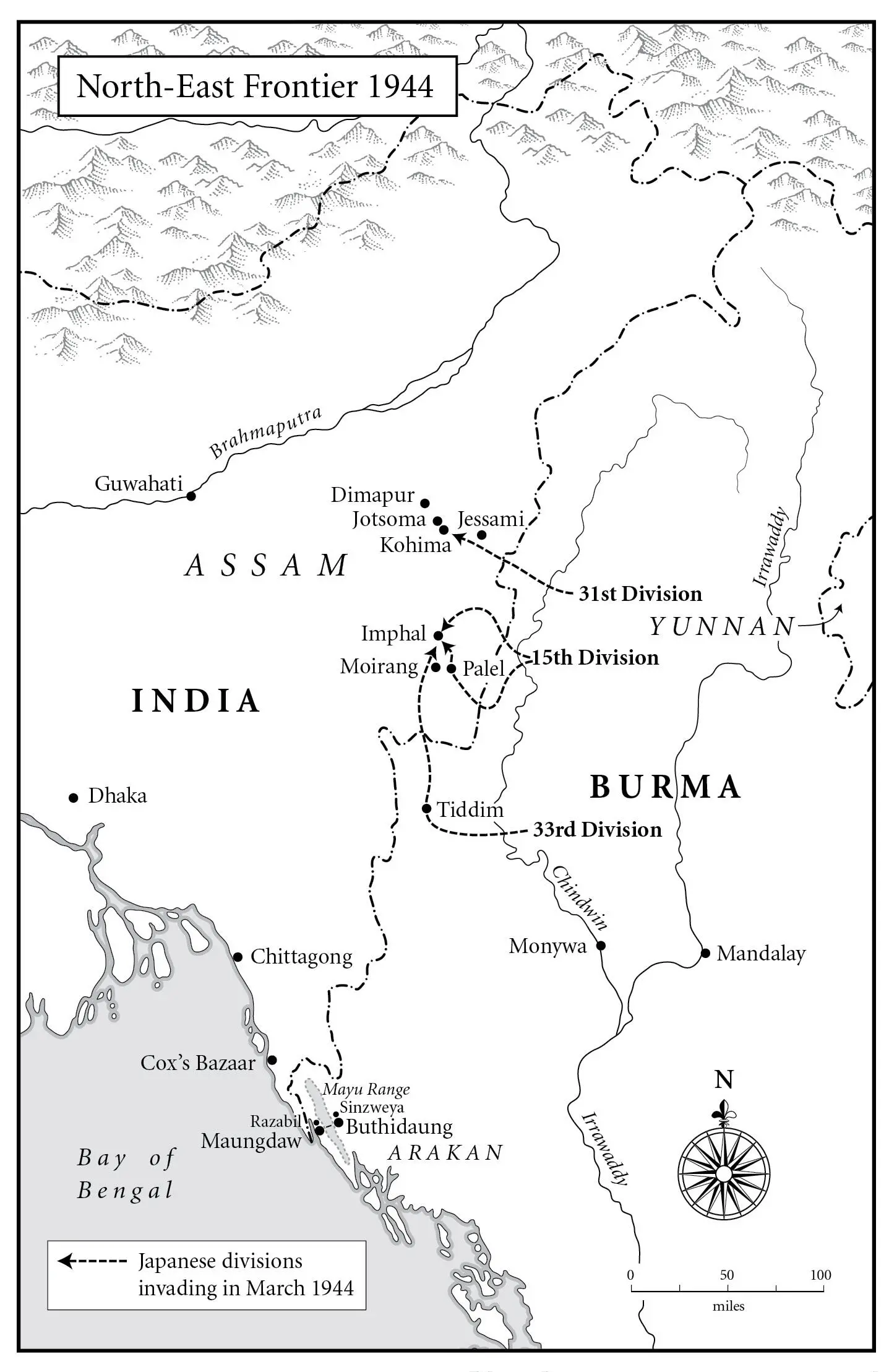

Maps by John Gilkes

The Author and Publishers are committed to respecting the intellectual property rights of others and have made all reasonable efforts to trace the copyright owners of the images reproduced, and to provide appropriate acknowledgement within this book. In the event that any untraceable copyright owners come forward after the publication of this book, the Author and Publishers will use all reasonable endeavours to rectify the position accordingly.

Cover images © Shutterstock

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008115722

Ebook Edition © June 2015 ISBN: 9780008115715

Version: 2016-04-25

For my mother,

who didn’t let me forget

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Maps

Prologue

PART ONE: Home

1. Everybody’s Friend: Calicut

2. Hukm Hai : Madras

3. Savages of the Stone Age: Miranshah

4. The Centre of the World: Madras

5. Madras Must Not Burn

6. Things Sacred Between Us: Mhow

7. Do or Die: Thal

8. The King’s Own: Roorkee

PART TWO: West

9. Second Field: Baghdad

10. The Jemadars’ Story: Eritrea and Libya

11. The Lieutenant’s Story: El Alamein

12. Kings of Persia: Baghdad

PART THREE: East

13. Enter the Hurricane: Imphal

14. No Heroes: Madras

15. Fascines and Gabions: Calcutta

16. The Jungle Book: Arakan

17. Fight with Your Ghost: Kohima and Jotsoma

18. The Cremation Ground: Kohima

19. The Elephant: Tiddim Road

20. The Road Ahead

Epilogue

Afterword

Acknowledgements

Notes

Appendix 1: Timeline

Appendix 2: The Indian Army

Select Bibliography

Index

About the Author

About the Publisher

I had known their faces my whole life, but never asked their names till it was too late. Their portrait-style photographs, full of grain and shadow, were not in albums – that would have placed them somewhere in the train of family history, and when the albums were opened, we’d have asked, ‘And who’s that?’ Instead they were isolated in dull silver frames on table tops around the house in Madras; beheld but not noticed, as angels are in a frieze full of mortal strugglers. I never even noticed that I looked like one of them.

I still can’t believe I was so late. By the time I asked, not only were those men long gone, but my grandmother was too, and her sisters, and most of their generation. Nugs, my grandmother, could have told me everything, though she might have refused. I think she had banished her youth from her mind by the time she died, though I don’t actually know. I never asked. I was a child, curious about anything but family. All I’d wanted from her was the hoard of gold which I believed was hidden under a clicking tile in her bedroom. She told me I could have it after she died. So, after she died, I knew precisely where to look for what had never existed. And what had existed – her story and the stories of those young men in the photo frames – I had to search for without her.

There was an injustice in it, which I sensed as it dawned on my mother how little she knew of their stories either – though one of the men was her own father, and the others her two uncles. She and my grandmother were always close, as I’d imagined a single child and bereaved parent had to be. Half a lifetime they had spent together, but neither one asked or told about what happened. My grandmother, a doctor, had sutured that past shut. Eventually they were both doctors, and when my mother moved away to work in New York for nearly twenty years she wrote back every week, and in the house in Madras I found every one of the thousand letters, bound up into bricks that could build a playhouse. Everything my grandmother could save of my mother’s, she had. But of the men, there was almost nothing.

Still my mother did know the names of those who, in the late hours of their lives, held onto strands of the story. With visit after visit, we followed the thinning thread of those lives, right up to the point where it frayed, came apart, and came to an end.

What I learned first, before I even learned their proper names, was that they had been in the Second World War. That was surprising. It was almost outlandish, because Indians never figured in my idea of the war, or the war in my idea of India, and I thought I had a good idea about both. There was certainly no public notion of it; nothing we were taught in school or regaled with from the silver screen, even though the Indian Army in the Second World War was the largest volunteer force the world had ever known. Personally, I hadn’t thought Madras could even be mentioned in the same book as Pearl Harbor; I was accustomed to thinking of the war as Western Front, Eastern Front and Pacific. When I looked through the eyes of Indian soldiers, however, the globe turned, revealing new continents.

The larger story was the key to retrieving what I could of their private stories. From the start, to learn what happened to my grandfather and grand-uncles was to discover the lost epic of India’s Second World War, as well as the reasons we chose to discard it. I started with names. To the family, they were Bobby, Manek and Ganny; their proper names, which I’d never seen in writing, I confirmed from a registry of Commonwealth soldiers. The registry also listed the units to which they belonged. With luck, I found those units’ diaries. This meant that in my desperate pursuit, even at times when I lost sight of them, I still knew the road they had taken.

Graham Greene describes Henry James as once saying that a writer with sufficient talent need only look in through the mess-room window of a Guards’ barracks in order to write a novel about the brigade. James didn’t say anything about non-fiction, but the challenge of this book felt similar. Could one write a true story on the basis of only glimpses into the lives of forgotten men?

Читать дальше