William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Copyright © Patrick Bishop 2017

Cover image: RAF bomber pilots return home from a successful mission (Photo © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

Maps by John Gilkes

Patrick Bishop asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007433155

Ebook Edition © September 2017 ISBN: 9780007433162

Version: 2018-05-29

TO HEN

ANGEL GIRL IN CHIEF

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Maps

Prologue: Firstway

1 The Big One

2 A Cottage or a Castle?

3 Smoke and Mirrors

4 Brylcreem Boys

5 ‘There’s Something in the Air’

6 ‘Tragic, Criminally Tragic’

7 The Battle

8 Fighting the Night

9 Ten Million Miles of Sea

10 The Blue

11 ‘Eat, Drink and Be Merry …’

12 ‘Britain’s Best Advertisement’

13 Out of Sight

14 Black and White

15 The Hyacinths of Spring

Epilogue: Brothers and Sisters

Acknowledgements

Notes

Picture Section

Index

Also by Patrick Bishop

About the Author

About the Publisher

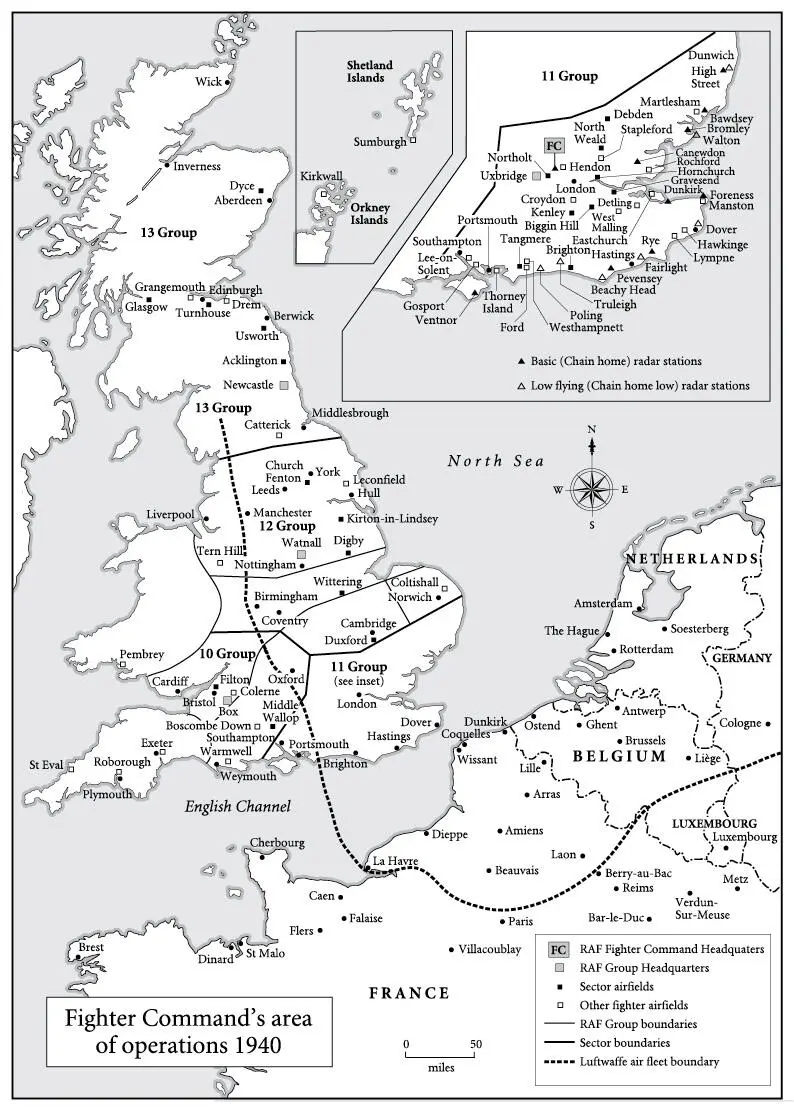

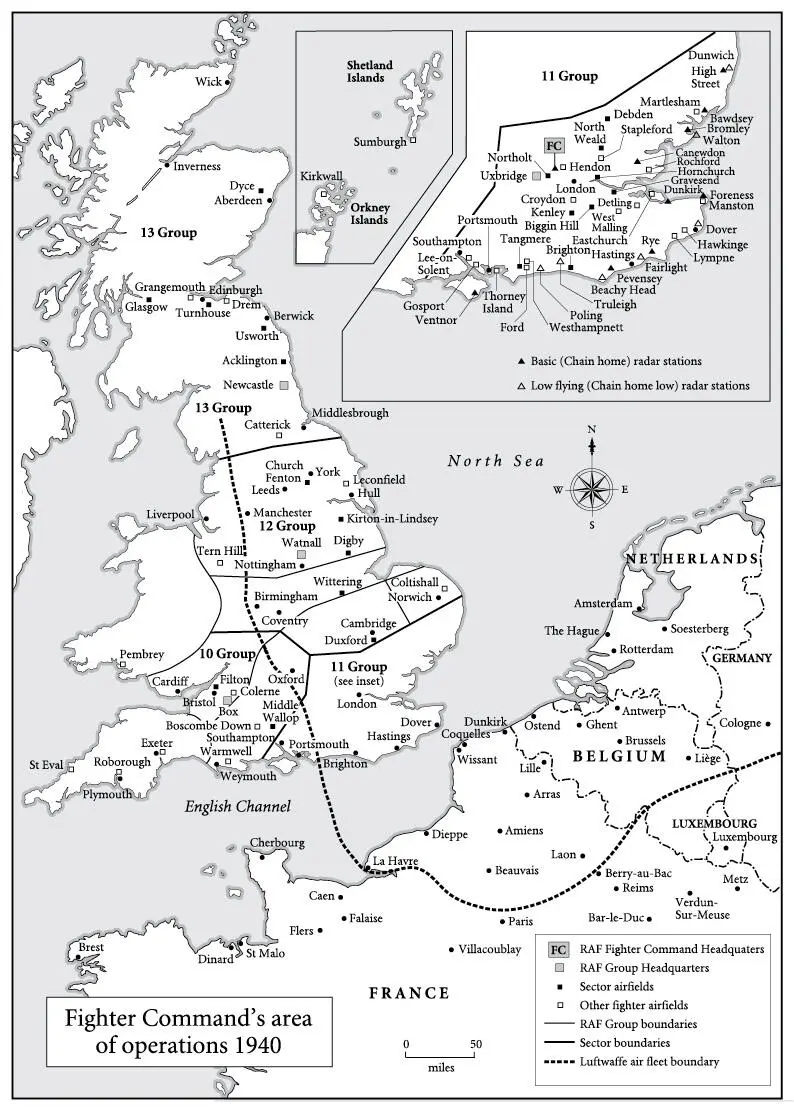

Fighter Command’s area of operations 1940

Main Bomber Command stations in the UK

Main targets in Europe

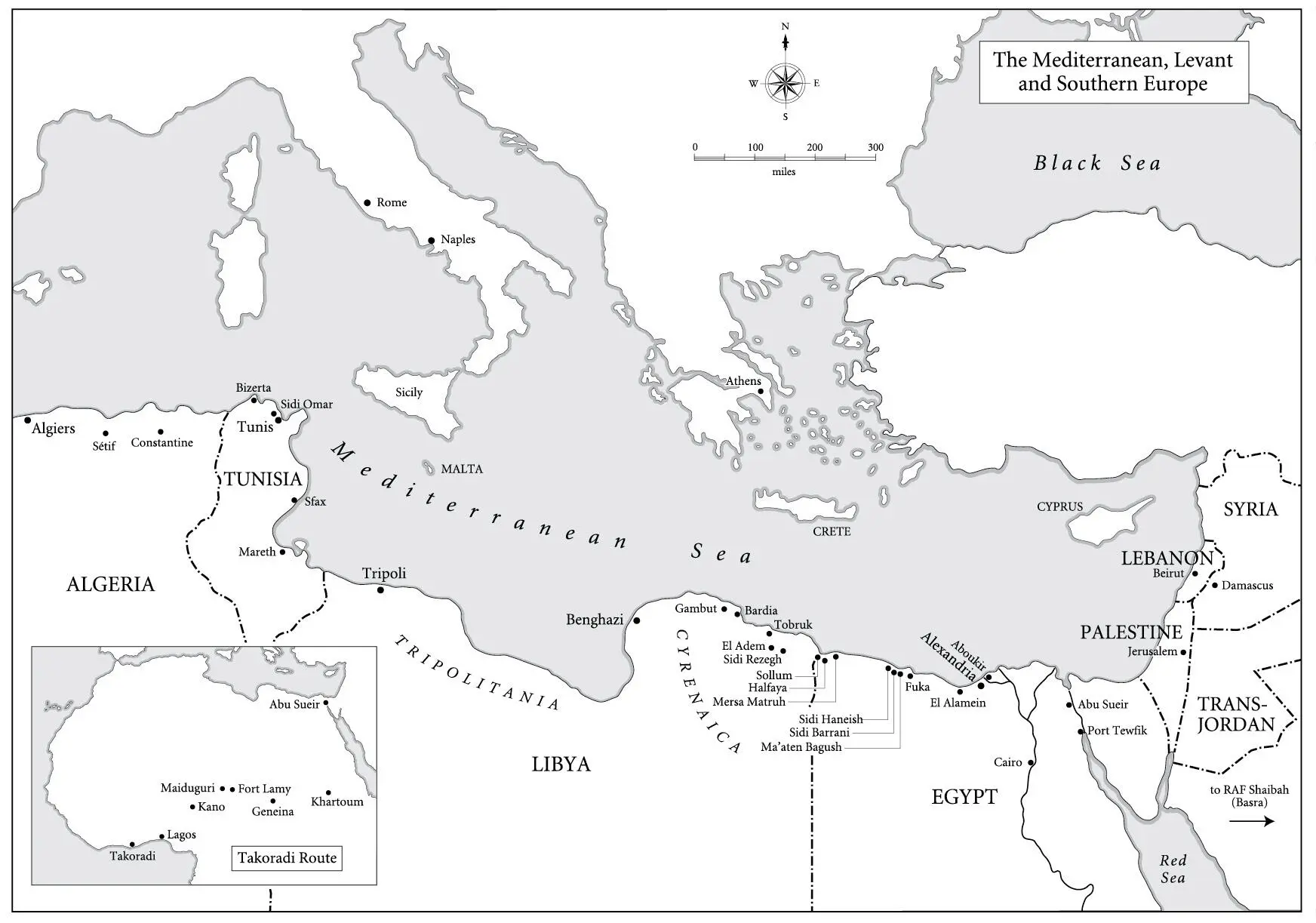

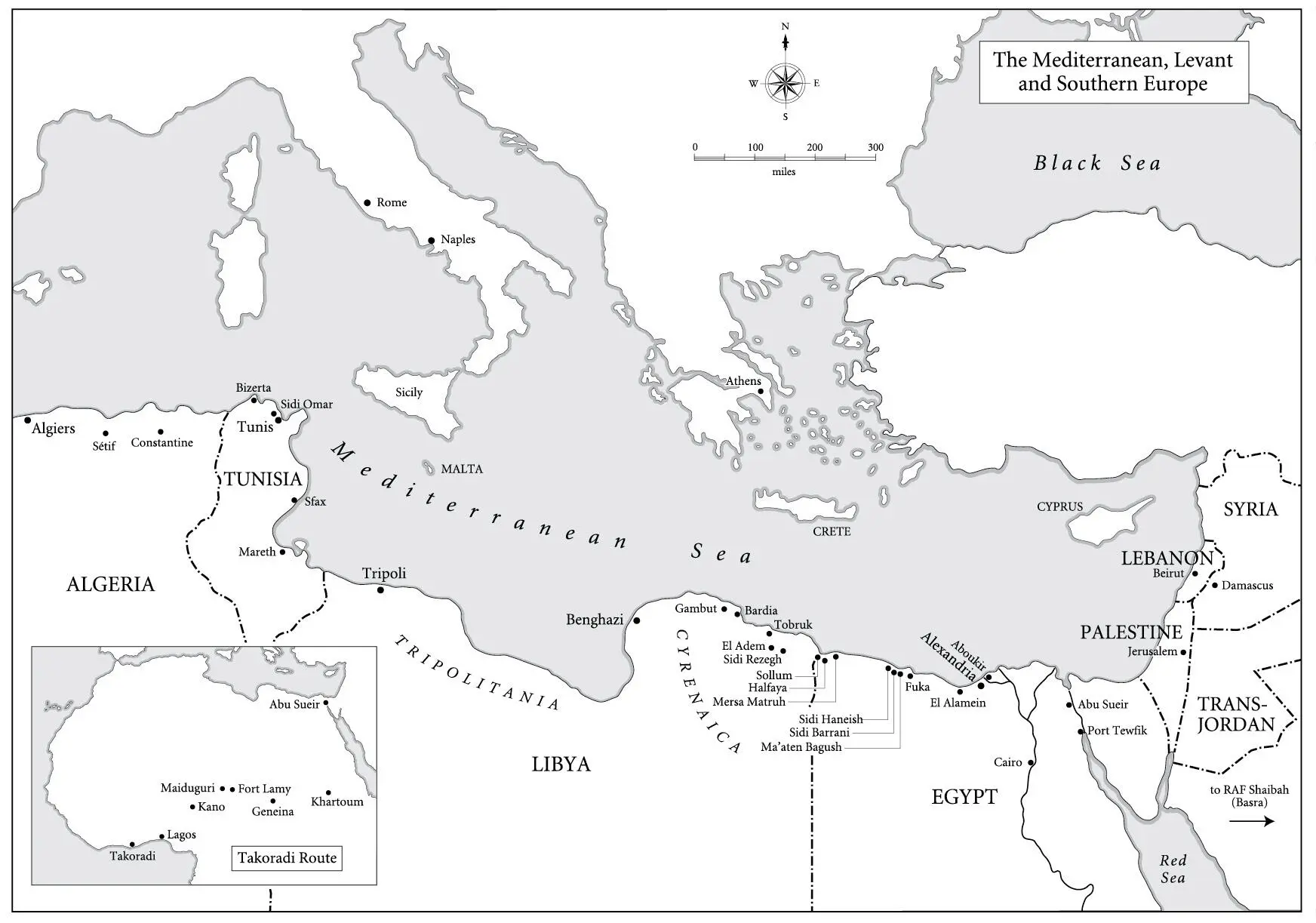

The Mediterranean, Levant and Southern Europe, showing the Takoradi Route

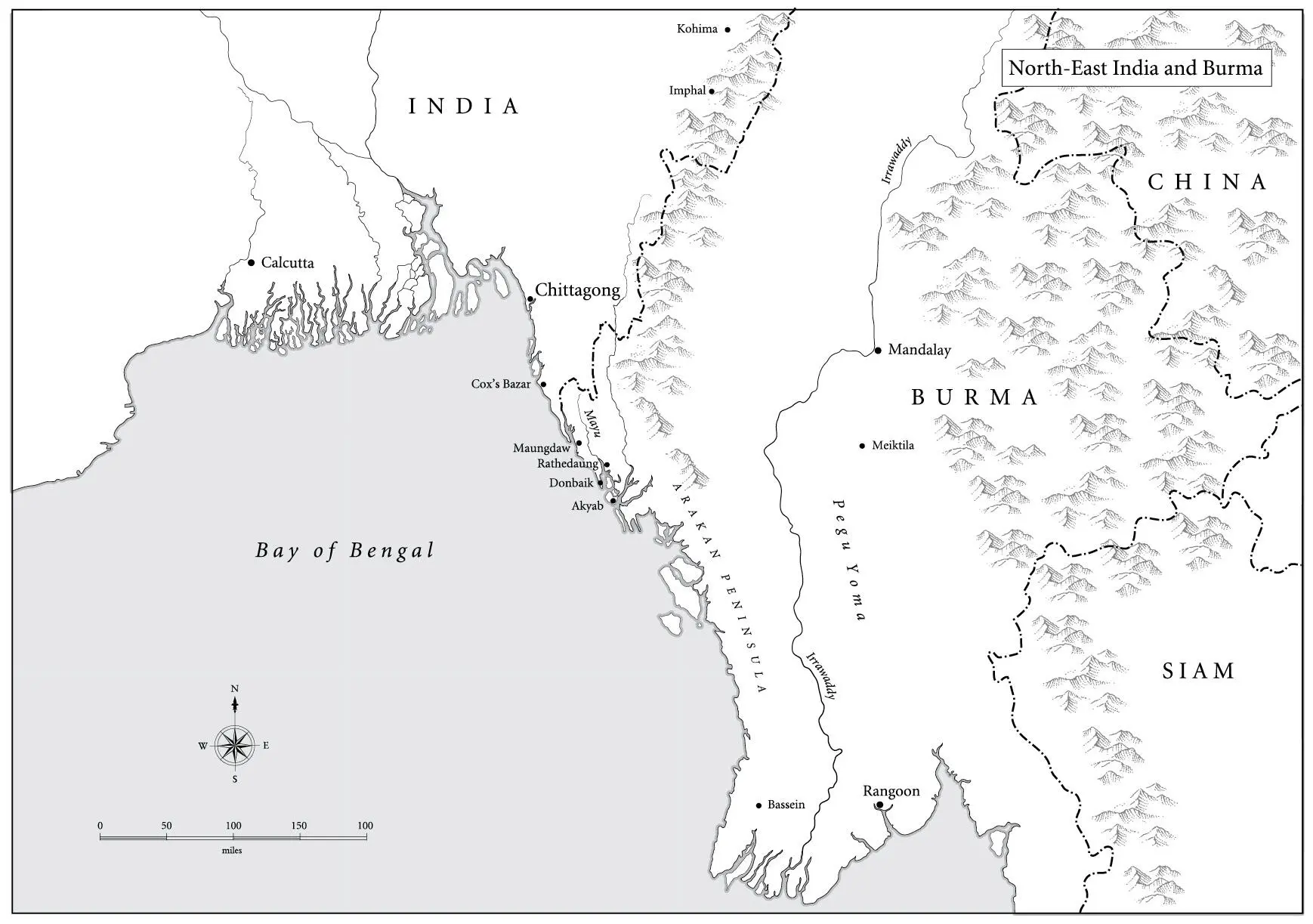

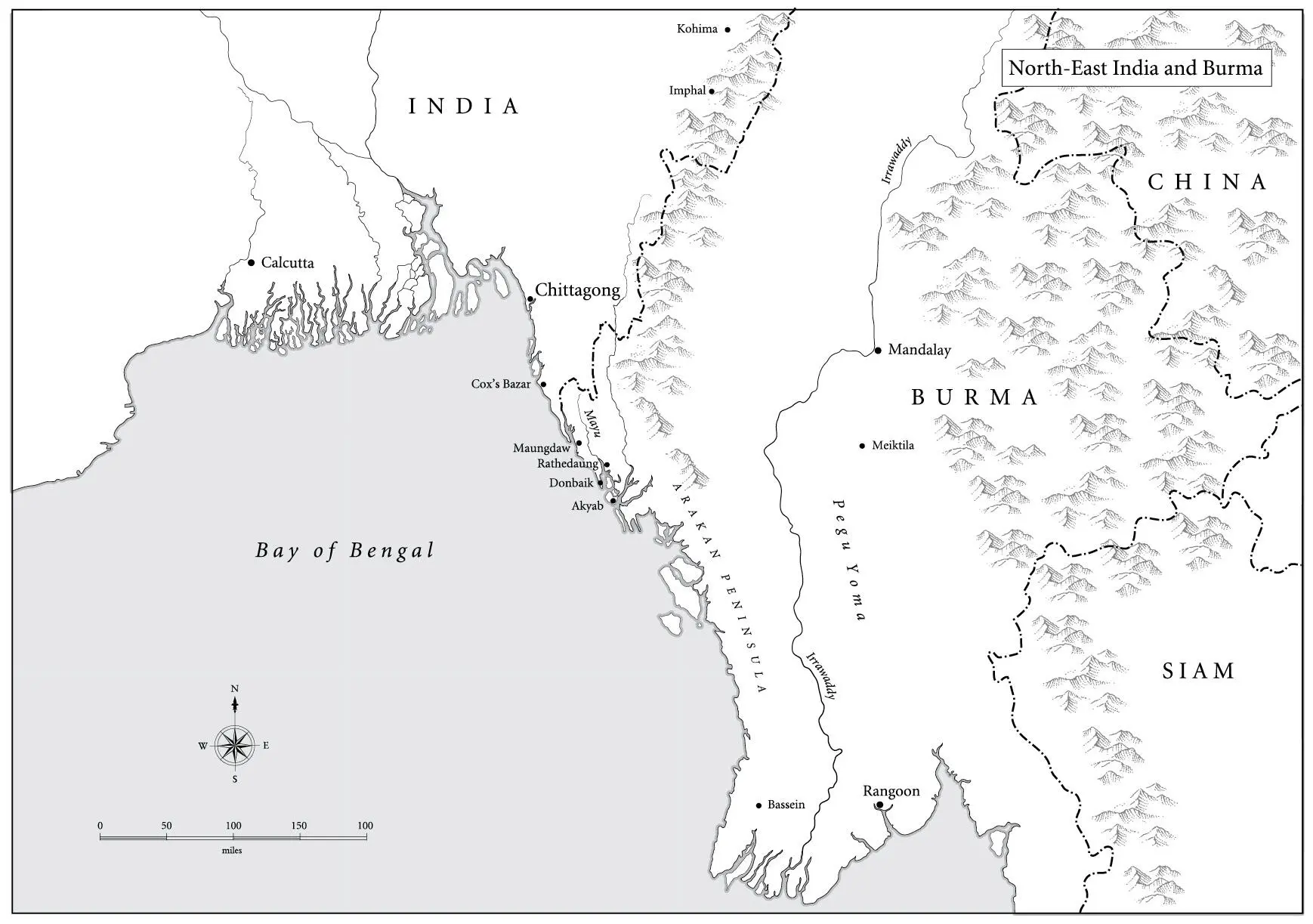

North-East India and Burma

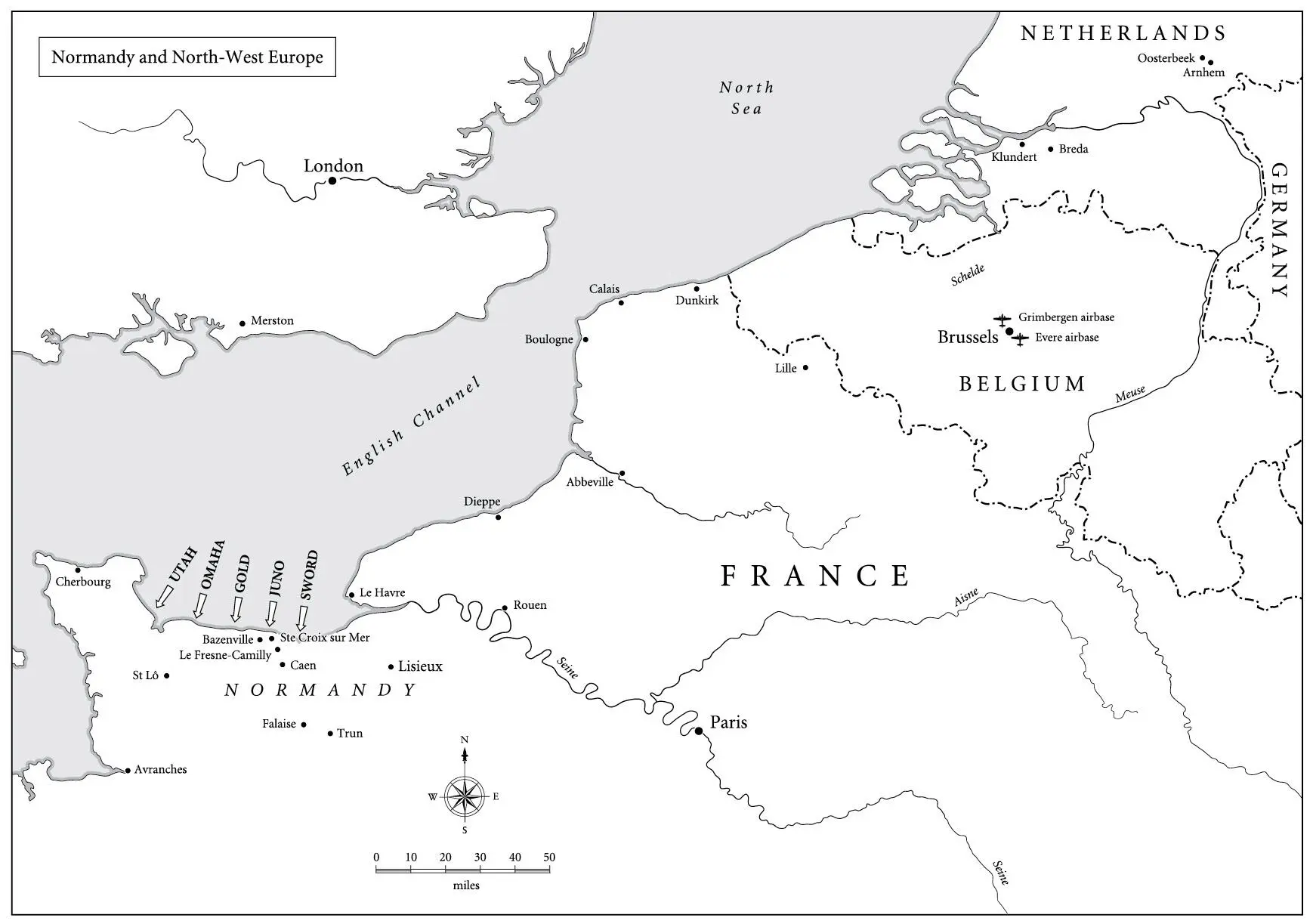

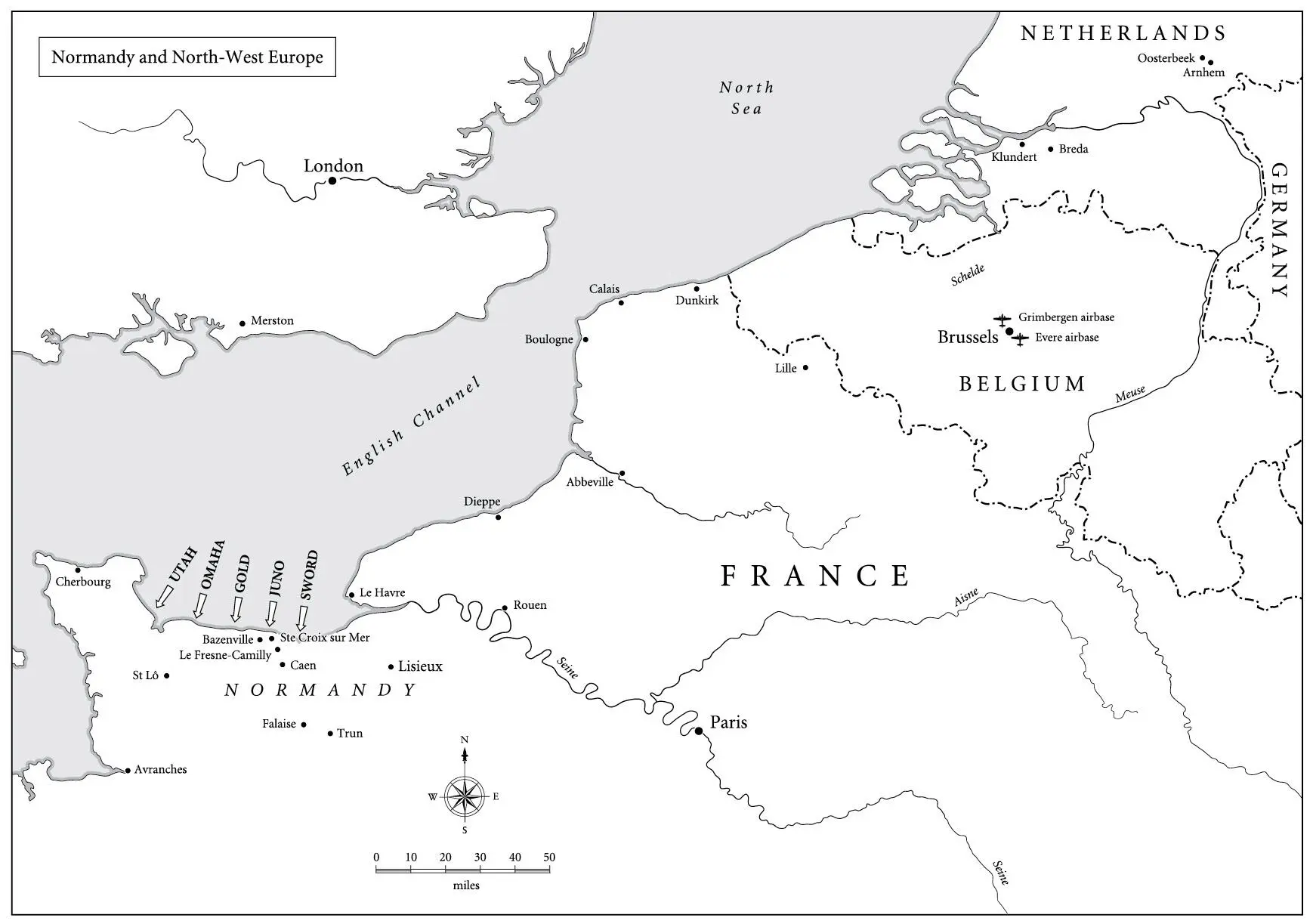

Normandy and North-West Europe

Prologue

In the spring of 1944 the chief information officer with the Royal Air Force permanent delegation in Washington, DC, reported back to London on how the service was regarded on the other side of the Atlantic. ‘We cannot hope to enhance the prestige of the RAF,’ he wrote. ‘Throughout the world it is a household word, and in the United States its reputation is so high that in some quarters it is almost regarded as something apart from, and superior to, Britain.’ 1

The Americans were not easily impressed. Since joining the war they had become the dominant partners in the alliance and the attitude of US commanders towards the British Army and Navy could be tinged with a condescension that was sometimes amused and often exasperated.

The information officer’s report, smug though it sounded, was essentially accurate. The RAF was seen differently. Unlike the other services, it attracted quasi-automatic admiration and respect. American airmen regarded their British comrades as something like equals; energetic, efficient and providing an operational contribution that added real weight to the Allied war effort.

In March 1944 when the report was written, Britain and the US had settled on the command structure for the forthcoming great invasion of northern Europe, and Dwight D. Eisenhower was chosen as Supreme Allied Commander. Eisenhower knew who he wanted as his second-in-command: Arthur Tedder of the RAF, who he had got to know intimately during the Mediterranean and Italian campaigns. ‘Ike’ had been Tedder’s best man when he married for the second time. Tedder was Eisenhower’s ‘warm personal friend’ 2and the man he most admired and trusted among the British high command.

The US military’s assessment of the quality and worth of their allies was based initially on observation, then on direct experience. For the first ten months of the war the Army’s record was one of debacle and defeat in Norway and France ending in the ignominy of Dunkirk. In North Africa, it floundered against a weaker enemy, and a golden chance for a quick ending was squandered when Churchill decided to switch forces to Greece in a hopeless attempt to stem the Nazi invasion. The eventual victory at El Alamein was the result of a marked numerical superiority in men, guns, tanks and aircraft. It was the first and last time that a British and Commonwealth force would beat the Germans on their own. Thereafter almost all of the Army’s effort in the West would be in conjunction with, and ultimately subordinate to, the Americans.

At sea, the war disobligingly failed to develop along the lines that the Admiralty had planned for. There would be no major fleet showdown between the Royal Navy and the Kriegsmarine and the huge and expensive battleships the admirals set such store by absorbed commensurate resources and manpower, which had to be diverted from more productive activities in order to protect them. The Navy did, of course, secure at great cost and effort the sea lanes that kept Britain in the war, but the Battle of the Atlantic was a struggle for survival rather than an advance towards victory. Fighting it took all their time and British warships did not contribute anything to the US Navy’s campaign in the Pacific until January 1945.

The information officer’s belief that the Air Force was perceived as something ‘apart from’ and ‘superior to’ Britain was telling. The Americans did not do sentimentality. The notion that cultural and historical connections meant that Britain was owed deference had long ago vanished. Some in the British military and political establishment did not seem to have noticed that things had changed. Transatlantic visitors were used to being talked down to by their hosts, who drew on centuries of imperial wisdom to instruct and correct. Americans believed they had little to learn from a nation that was fast losing its world-power status and in the space of a generation had twice been forced to turn to them for salvation.

Читать дальше