No one had to feel sorry for the RAF. The aircrew could equal their Yank counterparts in swank and dash and even the earthbound ‘erk’ had the edge over his ‘brown job’ and matelot comrades. Their uniform may have been of serge but they wore a collar and tie to go to work and their hair, curling from under their distinctive two-button side caps at a length that would have given a sergeant-major apoplexy, was as like as not gleaming with Brylcreem.

It was no longer the case that all the nice girls loved a sailor. In October 1939 ‘Just An Airman’ wrote to Picture Post complaining that after joining the Air Force his girlfriend had dumped him and since then he had found that ‘no decent girl seems to look at an airman’. He went on: ‘I am five feet 10 inches tall, good at sports and reasonably good looking. Once I had girlfriends. Now the only place I seem welcome is at the public house.’12

His self-pitying and possibly self-serving missive produced an avalanche of positive responses, a selection of which was printed over a double-page spread. ‘I, as a young lady of nineteen, was very surprised to read your correspondent’s letter,’ wrote Joyce Dickinson of London Road, Rainham, Gillingham, Kent.13 ‘Many young ladies, including myself, admire members of the Royal Air Force and feel especially proud when we read of their daring and brave exploits on the Western Front and over Germany. He may rest assured that although one girl has turned him down, many of us would like the opportunity to make his acquaintance.’

From Wallasey in Cheshire ‘An Admirer’ declared: ‘I think many readers will agree with me when I say that the RAF is the finest of the three services. I am not saying anything against the Navy or the Army … but I prefer the Air Force.’

It was little wonder that when conscription began more men exercised their right of choice in favour of the Air Force over the other services. The RAF seemed immune to the criticism that the Army in particular sometimes attracted. The war in the air got off to just as bad a start as it did on land and sea. Bomber Command’s early record was one of continuous failure and heavy, pointless losses, and the pattern was maintained by all branches of the service in the campaigns in Norway and France. Government propaganda and a co-operative media skated over this truth.

Then, in the summer of 1940, in full view of the population, Fighter Command won the Battle of Britain, supercharging national morale and gilding the Air Force with an aura of success that never tarnished. ‘The RAF are the darlings of the nation!’ wrote John Thornley, a twenty-nine-year-old salesman from Preston, Lancashire, in his diary in July 1940.14 ‘What magnificent chaps the RAF pilots must be,’ he declared a month later as the Battle approached its climax.

By the end of the summer its reputation seemed unassailable. Britain’s city-dwellers proved remarkably willing to overlook Fighter Command’s inability to protect them from the nightly Blitzes that devastated their homes in the winter of 1940–41, preferring to blame politicians for the lack of counter-measures. Major flaws in the Air Staff’s thinking and preparations such as its blind faith in strategic bombing and the initial failures to co-operate effectively with the Army and Navy were never really exposed to public view. The RAF’s numerous critics in the upper echelons of the other services complained that it appeared subject to different rules from the ones they had to obey. Often it seemed a law unto itself, holding, in the opinion of the soldier-historian Bernard Fergusson, ‘an unwritten charter direct from the war Cabinet’ that allowed it to direct bombing policy and decide on what types of aircraft were needed without having to consult with soldier and sailor colleagues.15

In two previous books, Fighter Boys (2003) and Bomber Boys (2008) I told the story of the RAF in the Battle of Britain and the Strategic Offensive against Germany, conveying events, emotions and attitudes as much as possible from the perspectives of the participants. In this final work in the trilogy, I hope to extend the field of vision to the whole of the Second World War. A comprehensive history is impossible in one volume. There was too much being done by too many people. Instead I have tried to examine essential aspects of the RAF wartime experience, both for those flying and those on the ground in selected battles and theatres, in the process, I hope, colouring in the RAF’s distinct identity. So this is not a chronicle of the war in the air. It is about the spirit of the Air Force, its heart and soul.

Again, I have tried to see things through the eyes of the players, relying wherever possible on contemporary documents, diaries and letters and, where they are not available, memoirs and reminiscences. I was lucky enough to meet and interview many veterans during my earlier research and could draw on their memories of other parts of their service not covered in previous books. There is, I was pleased to discover, still much rich material lying undiscovered in the archives which provides new evidence and insights.

This book is about many things but a recurrent theme is the special relationship that the Air Force enjoyed with the nation at this uniquely testing time in its history. For much of the war the RAF was Britain and Britain was the RAF. The conflict arrived in the middle of a time of great transformation, when British characteristics and attitudes were undergoing profound changes.

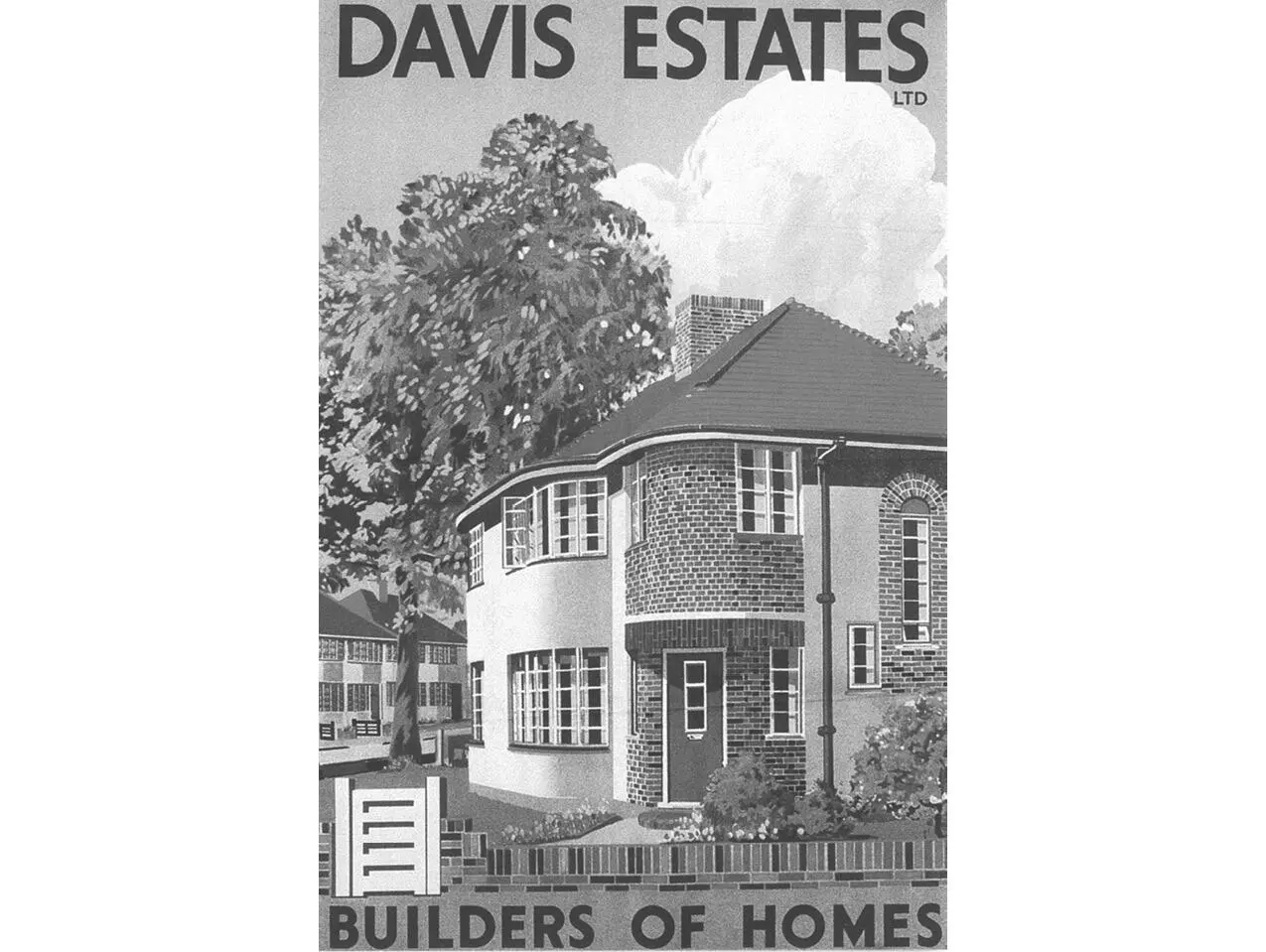

Davis Estates advert, 1930s ( Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo )

Among the girls who responded to ‘Just An Airman’ was Joyce Robinson of Firstway, Raynes Park, London SW20. She, too, was an Air Force fan, admiring ‘the spirit of adventure which prompts a man to join’.16 The street is half a mile from where I grew up. It was built in the 1920s by an energetic master builder called George Blay who turned much of what was then countryside into suburbia. It is a tree-lined cul-de-sac of nice, three-bedroomed terraced houses, with bay windows, timberwork on the façades and ample back gardens. They cost £675 (with 85 per cent mortgages available) and were a few minutes’ walk from Raynes Park station on the Southern Electric railway which ran straight in to Waterloo. Thousands of streets like Firstway were springing up around Britain’s cities at the same time.

The families who lived in them were members of the most overlooked and underappreciated stratum of the social layer cake – the lower-middle class. The cautious patriarchs of these ‘quadrants’, ‘crescents’, ‘drives’ and ‘walks’ left each morning for their jobs as clerks, draughtsmen, shopkeepers and minor civil servants while Mum stayed home to clean and cook. Their children raised their eyes to broader horizons. I have not managed to discover anything about Joyce Robinson but I have imagined her: playing tennis at the club round the corner in Taunton Avenue, watching Clark Gable in Gone With the Wind at the Raynes Park Rialto, taking the District Line to Hammersmith to dance at the Palais, perhaps driving with a boyfriend to a roadhouse on the Kingston by-pass.

It was this emerging Britain which provided the wartime Air Force with much of its man- and womanpower as well as enriching its identity and ethos. There were fewer men and women in Air Force blue than there were in Navy blue or khaki. The Second World War was nonetheless in many ways an RAF show. From the beginning to the end it was the spearhead of almost every action and effort. Not only did it lead the way to victory, it shaped the contours of peace.

Читать дальше