3 View of Blenheim Palace from the column of Victory. © Skyscan.

Page 8

1 Rear wall painting of the Upper Hall at Greenwich glorifying George I and the House of Hanover, by Sir James Thornhill. Courtesy of the Greenwich Foundation for the Old Royal Naval College.

SECTION IV

Page 1

1 The pediment of the Temple of Concord and Victory, c.1735, at Stowe Landscape Garden. Courtesy of Stowe School Photographic Archive (M. Bevington).

2 Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, Studio of Jean Baptiste van Loo, 1740, (oil on canvas). The National Portrait Gallery, London.

3 William Pitt the Elder, 1st Earl of Chatham, studio of William Hoare, c.1754, (oil on canvas). The National Portrait Gallery, London.

Pages 2–3

1 George Washington, by Gilbert Stuart. © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA/The Bridgeman Art Library.

2 Thomas Jefferson, 3rd President of the United States, by James Sharples, c.1797, (oil on canvas). © Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, UK/The Bridgeman Art Library.

3 Wren building of the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, USA. © G.E. Kidder Smith/CORBIS.

4 George III in his Coronation Robes, by Allan Ramsay, 1761. © Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh/Bridgeman Art Library.

5 Edmund Burke, studio of Sir Joshua Reynolds, c.1767–69, (oil on canvas). The National Portrait Gallery, London.

6 The severed head of Louis XVI, King of France, in the hands of the executioner, (Stipple engraving). Photo: akg-images, London.

Pages 4–5

1 The Plum Pudding in Danger, by James Gillray, 1805, (colour engraving). © Private Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library.

2 King George IV in Highland Dress, 1830, (oil on canvas), Sir David Wilkie. Apsley House, The Wellington Museum, London/The Bridgeman Art Library.

3 The Quadrant, Regent Street, from Piccadilly Circus, published by Ackermann, c.1835–50, (coloured aquatint). © Private Collection/ The Stapleton Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Pages 6–7

1 King William IV, by Sir Martin Archer Shee, c.1800, (oil on canvas). The National Portrait Gallery, London.

2 Sir Herbert Taylor, Private Secretary to King William IV, by John Simpson, exhibited 1833, (oil on canvas). The National Portrait Gallery, London.

3 The House of Commons, 1833, by Sir George Hayter, 1833–1834, (oil on canvas). The National Portrait Gallery, London.

Page 8

1 The Royal Family in 1846, Franz Xavier Winterhalter, 1846. The Royal Collection © 2006, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

2 Opening of the Great Exhibition by Queen Victoria on 1st May 1851, Henry Courtney Selous, 1851–52. © V&A Images, London.

GENEALOGIES CONTENTS GENEALOGY INTRODUCTION: The Imperial Crown PART I 1 The Man Who Would Be King 2 King and Emperor 3 Shadow of the King 4 Rebellion 5 New Model Kingdom PART II 6 Restoration 7 Royal Republic 8 Britannia Rules 9 Empire 10 The King is Dead, Long Live the British Monarchy! EPILOGUE: The Challenges of Modernity INDEX Also by David Starkey Credits Copyright About the Publisher

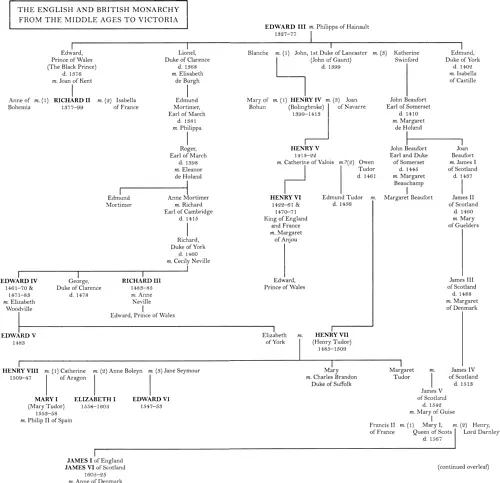

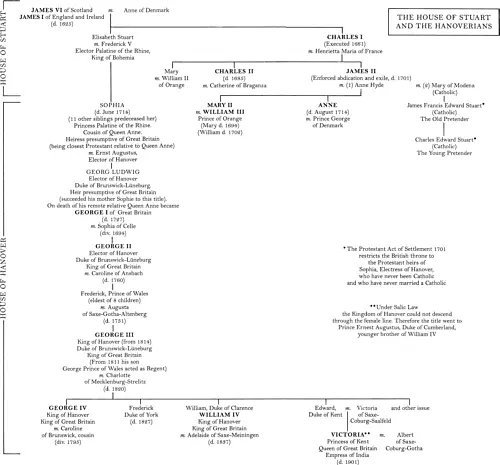

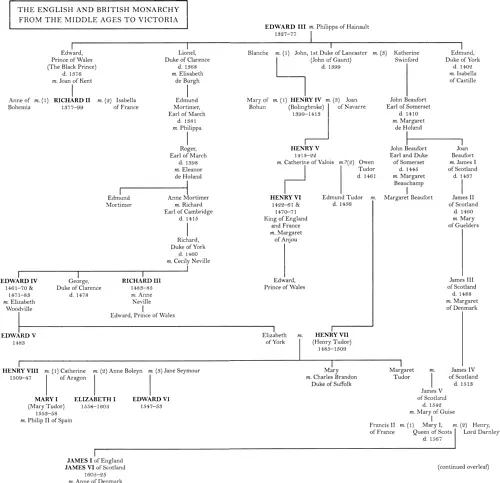

The English and British Monarchy from the Middle Ages to Victoria

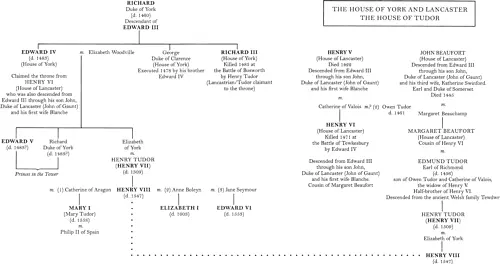

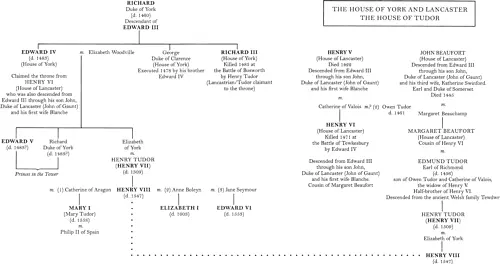

The House of York and Lancaster, The House of Tudor

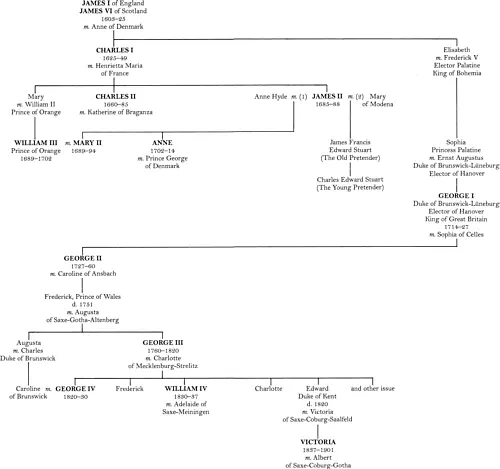

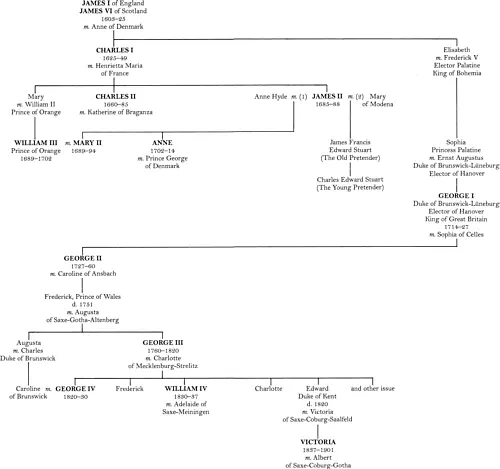

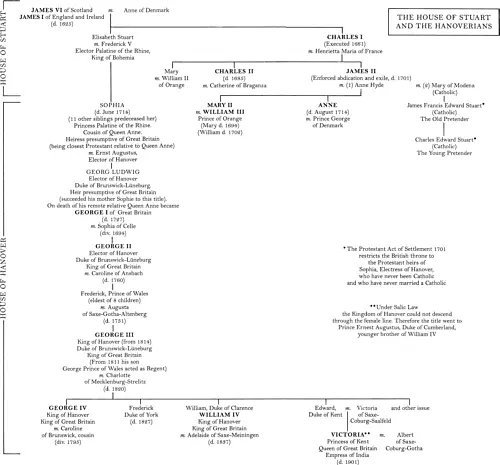

The House of Stuart and the Hanoverians

INTRODUCTION CONTENTS GENEALOGY INTRODUCTION: The Imperial Crown PART I 1 The Man Who Would Be King 2 King and Emperor 3 Shadow of the King 4 Rebellion 5 New Model Kingdom PART II 6 Restoration 7 Royal Republic 8 Britannia Rules 9 Empire 10 The King is Dead, Long Live the British Monarchy! EPILOGUE: The Challenges of Modernity INDEX Also by David Starkey Credits Copyright About the Publisher

THE IMPERIAL CROWN CONTENTS GENEALOGY INTRODUCTION: The Imperial Crown PART I 1 The Man Who Would Be King 2 King and Emperor 3 Shadow of the King 4 Rebellion 5 New Model Kingdom PART II 6 Restoration 7 Royal Republic 8 Britannia Rules 9 Empire 10 The King is Dead, Long Live the British Monarchy! EPILOGUE: The Challenges of Modernity INDEX Also by David Starkey Credits Copyright About the Publisher

IN LATE 1487, King Henry VII had much to celebrate. In the space of only two years he had won the crown in battle; married the heiress of the rival royal house; fathered a son and heir; and defeated a dangerous rebellion. Secure at last on the throne, he decided to commemorate the fact in the most dramatic way possible by commissioning a new crown. And he would first wear it on the Feast of the Epiphany, 6 January 1488, at the climax of the Twelve Days of Christmas, when the monarch re-enacted the part of the Three Kings who had presented their gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh to the Christ Child.

The new ‘rich crown of gold set with full many precious stones’ caused a sensation. As well it might. The circlet was thickly encrusted with rubies, sapphires and diamonds, highlighted with large and milky pearls. From the circlet there rose five tall crosses alternating with the same number of similarly proportioned fleur-de-lis . These too were thickly set with stones and pearls, with each fleur-de-lis in addition having on its upper petal a cameo carved with an image of sacred kingship. The crown was surmounted by two jewelled arches, with, at their crossing, a plain gold orb and cross, and it weighed a crushing seven pounds.

It was the Imperial Crown of England. As such it sits on the table at the right hand of Charles I in his family portrait by van Dyck as the symbol of his kingly power.

This book is the story of the Imperial Crown and of those who wore it, intrigued for it and, like Charles I himself, died for it. They include some of the most notable figures of English and British history: Henry VIII, whose mere presence could strike men dumb with fear; Elizabeth I, who remains as much a seductive enigma as she did to her contemporaries; and Charles I, who redeemed a disastrous reign with a noble, sacrificial death as he humbled himself, Christ-like and self-consciously so, to the executioner’s axe.

Such figures leap from the page of mere history into myth and romance. And they do so, not least, because of the genius of their court painters, such as Holbein and van Dyck, who enable us to see them as contemporaries saw them – or, at least, as they wanted to be seen.

I have painted these great royal characters – and a dozen or so other monarchs, who, rightly or wrongly, have left less of a memory behind – with as much skill as I can. But this is not a history of kings and queens. And its approach is not biographical either. Instead, it is the history of an institution: the monarchy. Institutions – and monarchy most of all – are built of memory and inherited traditions, of heirlooms, historic buildings and rituals that are age-old (or at least pretend to be). All these are here, and, since I have devoted much of my academic career to what are now called court studies, they are treated in some detail.

Читать дальше