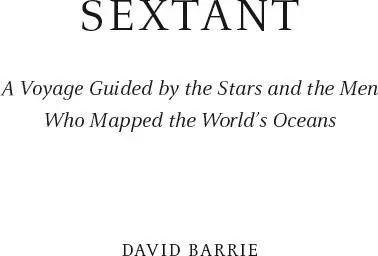

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2014

Copyright © David Barrie 2014

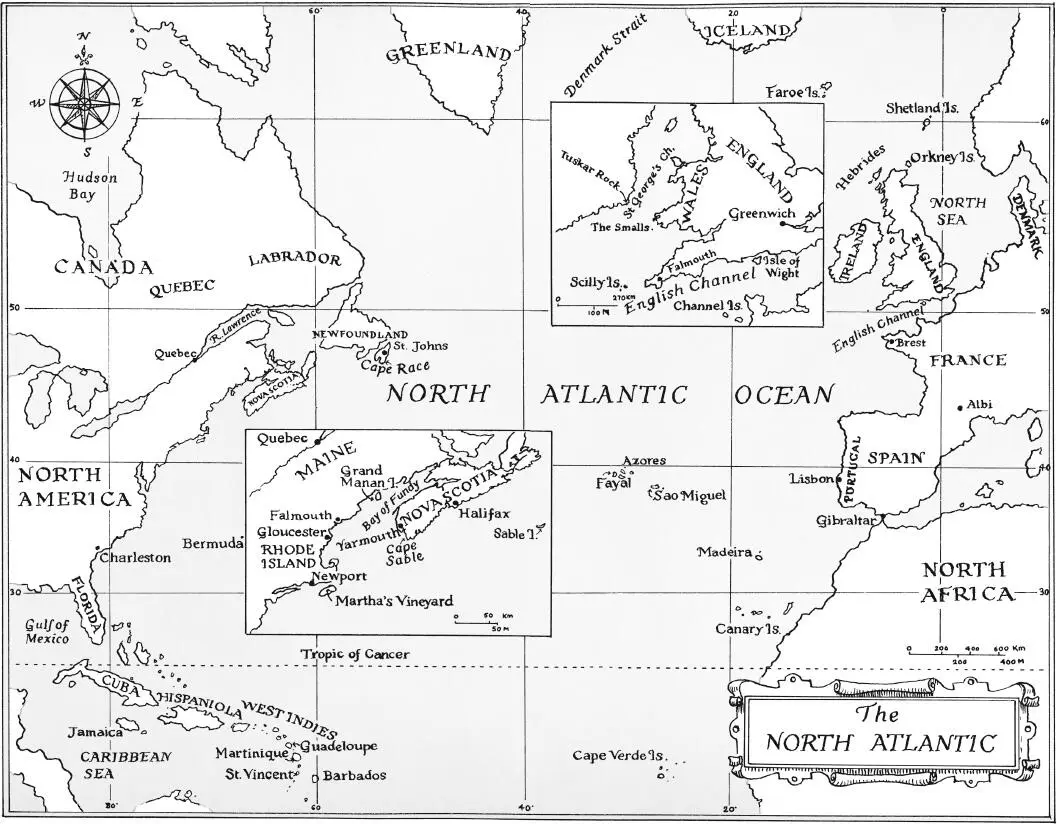

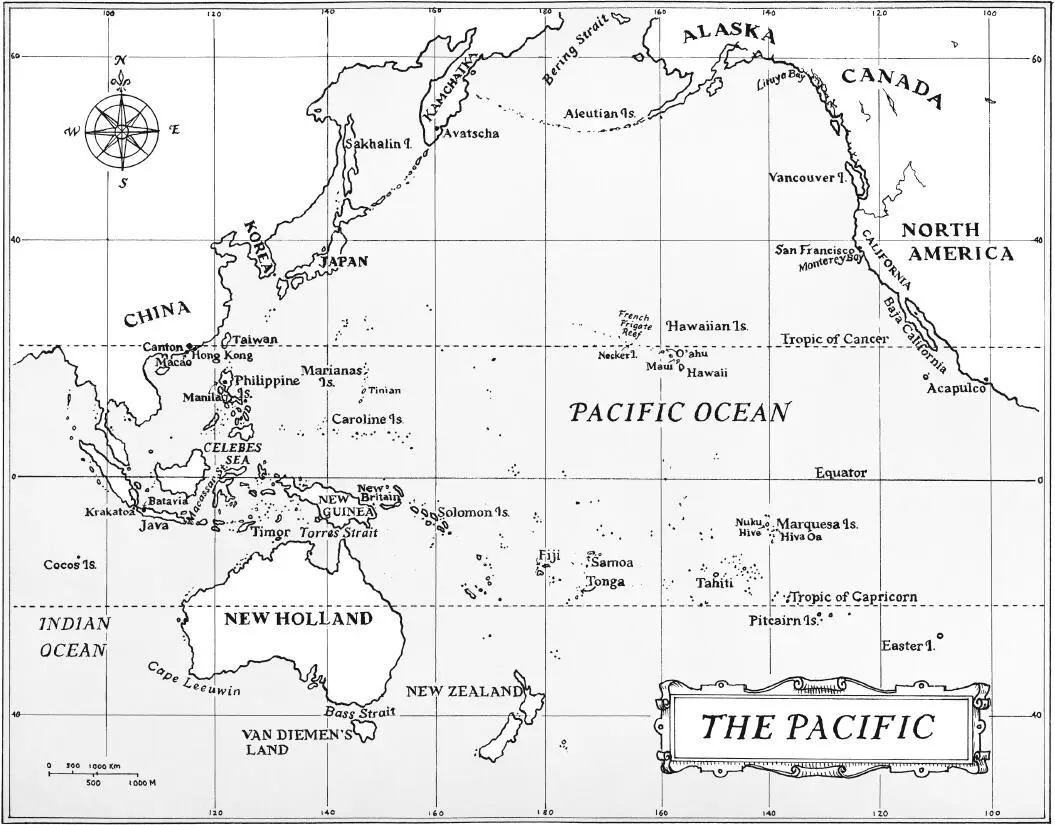

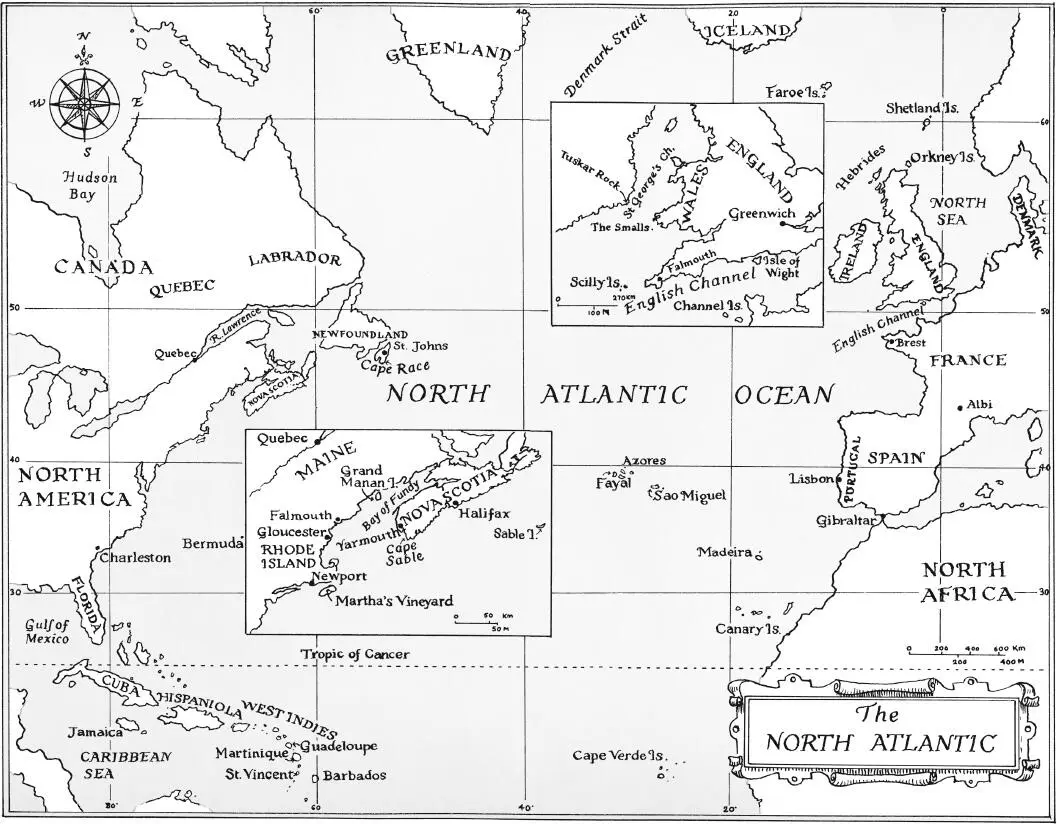

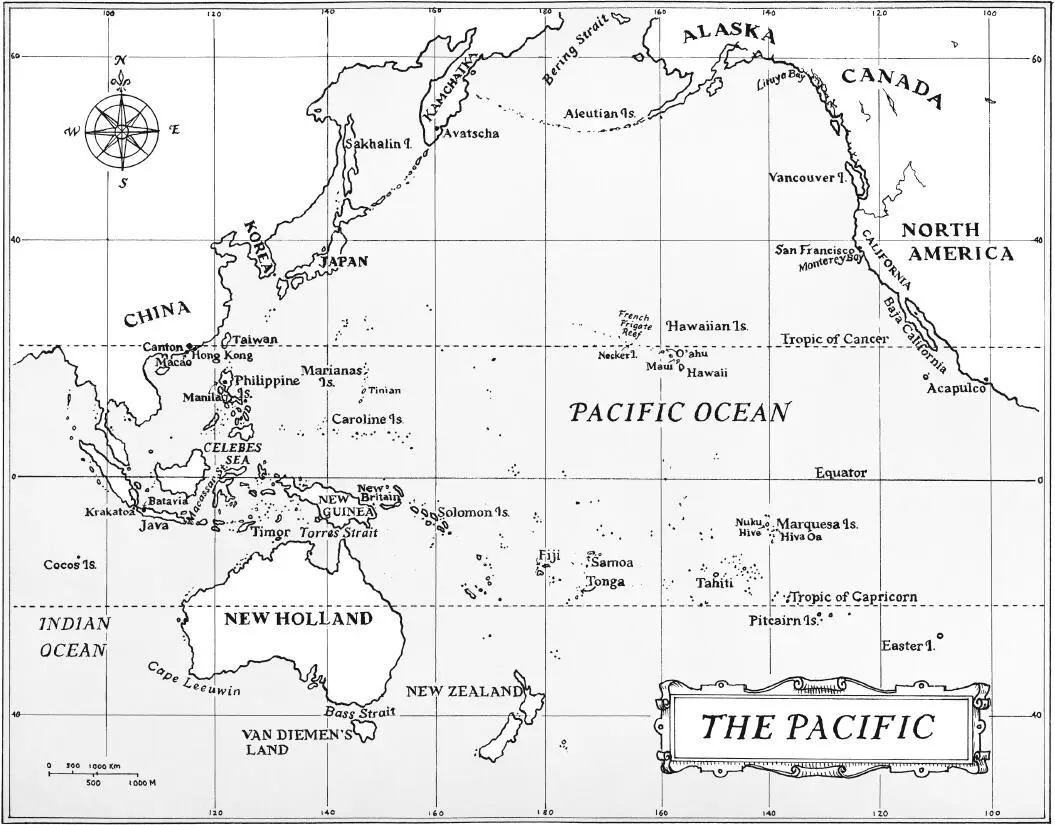

Maps © Nicolette Caven

David Barrie asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007516568

Ebook Edition 2014 ISBN: 9780007516575

Version: 2015-05-16

To the memory of my father, Alexander Ogilvy Barrie (1910–1969), who first showed me the stars, and of Colin McMullen (1907–1991), who taught me to steer by them.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Maps

Preface

Chapter 1: Setting Sail

Chapter 2: First Sight

Chapter 3: The Origins of the Sextant

Chapter 4: Bligh’s Boat Journey

Chapter 5: Anson’s Ordeals

Chapter 6: The Marine Chronometer

Chapter 7: Celestial Timekeeping

Chapter 8: Captain Cook Charts the Pacific

Chapter 9: Bougainville in the South Seas

Chapter 10: La Pérouse Vanishes

Chapter 11: The Travails of George Vancouver

Chapter 12: Flinders – Coasting Australia

Chapter 13: Flinders – Shipwreck and Captivity

Chapter 14: Voyages of the Beagle

Chapter 15: Slocum Circles the World

Chapter 16: Endurance

Chapter 17: ‘These are men’

Chapter 18: Two Landfalls

Epilogue

Picture Section

Footnotes

Notes

List of Illustrations

Bibliography

Glossary of Technical Terms

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

Crossing an ocean under sail today is not an especially risky undertaking. Accurate offshore navigation – for so long an impossible dream – has now been reduced to the press of a button, and most modern yachts are strong enough to survive all but the most extreme weather. Even if errors, accidents or hurricanes should put a boat in danger, radio communications give the crew a good chance of being rescued. Few sailors now lose their lives on the open ocean: crowded inshore waters where the risk of collision is high are far more hazardous.

But it was not always so. When a young man called Álvaro de Mendaña set sail from Peru in November 1567 to cross the Pacific with two small ships, accompanied by 150 sailors and soldiers and four Franciscan friars, he faced difficulties so great that his chances of survival, let alone achieving his objectives, were slim. 1

Mendaña’s orders from his uncle, the Spanish Viceroy, were to convert any ‘infidels’ he encountered to Christianity, but the expedition was certainly not motivated entirely by religious zeal. According to Inca legend great riches lay on islands somewhere to the west. Were these islands perhaps outliers of the great southern continent that was believed to lie hidden somewhere in the unexplored South Seas? Mendaña, who was twenty-five, hoped to find the answer, to set up a new Spanish colony, to make his fortune and win glory. However, any optimism he may have felt as the coast of Peru dipped below the horizon would have been misplaced. Although Magellan had managed to cross the Pacific from east to west in 1520–1, he had been killed in fighting with local people after reaching the Philippines, and only four out of the forty-four men who sailed with him aboard his small flagship had returned safely to Spain. 2This first, epic circumnavigation was counted as a brilliant success, but other expeditions ended in oblivion.

The challenges Mendaña faced were many. Not only was it impossible to carry sufficient fresh food and water for a voyage that might well last several months, but sailing ships were also vulnerable to the stress of weather, and the discipline of their rough and uneducated crews could never be relied on. First encounters with native peoples were fraught with danger, even if both sides were keen to avoid conflict, not least because cultural and linguistic differences made communication so difficult. If the Europeans brought with them infectious diseases that were to devastate native populations, tropical diseases also posed a serious threat to the visitors. To venture into the unexplored wastes of the Pacific was therefore to risk shipwreck, mutiny, warfare, disease, thirst, hunger and, most insidious of all, malnutrition.

After a passage of eighty days Mendaña’s two ships at last reached the ‘Western Islands’ in February 1568. Thinking at first that they had indeed found the legendary southern continent, Mendaña and his men explored the high, jungle-clad island on which they first landed and soon realized their mistake. They named it Santa Isabel, because they had sailed from Peru on that saint’s feast day, and went on to visit the neighbouring islands, which they called Guadalcanal, Malaita and San Cristóbal. Though a chief had greeted the Spanish visitors warmly on their first arrival, the natives could not satisfy their pressing demands for food; Mendaña had difficulty controlling his men – and blood, mostly native, soon flowed.

In August a disappointed Mendaña set sail from San Cristóbal. Having barely survived a hurricane, Mendaña and his officers had no idea where they were, how far they had travelled or when they might again reach land. Their few navigational tools would have included astrolabes and quadrants for determining latitude, magnetic compasses to steer by, hour-glasses for measuring short intervals of time, and lead-lines for sounding the depth in shallow water. But they had no proper charts and – crucially – no reliable means of judging how much progress they had made either to the east or to the west: only by estimating the ship’s speed through the water could the pilots assess how far they had travelled. This was a deeply unreliable method.

The agonizingly long return journey took Mendaña in a wide circuit across the North Pacific to reach the coast of Baja California in December 1568. He and his crew were reduced to a daily allowance of 6 ounces of rotten biscuit and half a pint of stinking water. Scurvy swelled their gums until they covered their teeth, they were racked by fever and many went blind. Every day they had to throw overboard another corpse. It was not until the following September that Mendaña finally reached Peru. He had found no riches, no continent, had made not a single convert and had failed to establish a colony, but his extraordinary voyage was to become a legend. Though he had been obliged to mortgage his property to get his ship repaired in Mexico, rumours spread that he had come home laden with gold and silver. The islands he had discovered were soon known by the name of the fabulously rich king of the Old Testament: Solomon. 3The longitude that he assigned to the Solomon Islands was so wildly inaccurate that subsequent explorers repeatedly failed to find them and eventually began to doubt their existence. 4It was to be 200 years before any European set foot on the Solomons again.

Читать дальше