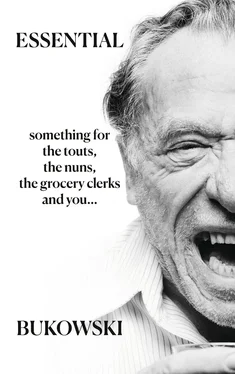

These ninety-two essential poems barely represent two percent of Bukowski’s mammoth output, but his poetic evolution is hard to miss in this chronological collection. The early poems, with their lyricism and occasional surreal imagery, give way in the 1970s to Bukowski’s “Dirty Old Man” macho persona, when he finally achieves success in his fifties, after which he takes, in his final years, a more philosophical stance on life. Through it all, what remains the same is Bukowski’s brilliance at capturing things as they are, his crystal-clear snapshots of his immediate experiences as well as the world at large, which he hardly ever photoshopped after the fact.

It is precisely this genuineness, along with the timeless quality of Bukowski’s most accomplished poems, that makes us embrace his poetry with open arms: the day-to-day but crucial trivialities found in “the shoelace”; the sensuality of “the shower”; the forces of life at work in “the mockingbird” and “the history of a tough motherfucker”; the elusive nature of art in many of the poems; the self-deprecating humor in “we’ve got to communicate”; the imperfection that makes us almost perfect in “one for the shoeshine man”; and the heartfelt portraits of the artists that Bukowski looks up to.

There’s also the striking, disarming simplicity of “art” and “nirvana”; the Hemingwayesque spare lines of “Carson McCullers” and “hell is a lonely place”; the hymns to individualism and willpower of “no leaders” and “the genius of the crowd”; the never-take-things-for-granted spirit of “I met a genius”; the long narrative poems that read as well-paced short-stories; and the life-affirming drive of “the laughing heart” and “the crunch.” These last two poems show that, despite the darkness that often entered his life and poetry, Bukowski always saw the light at the end of the tunnel, and we can’t help but identify with that feeling.

These poems are Bukowski at his most captivating: unvarnished, witty, and passionate, showing us all “the way” as he listens to classical music on “a radio with guts” and drinks “the blood of the gods” in his small Los Angeles apartments and studios. The Buddha of San Pedro, Bukowski ultimately smiles because he knows the secret of it all is way beyond him, and that’s the beauty of it: Bukowski distills life to its very essence, squeezing the magic out of the ordinary with his unmistakable, surpassing simplicity.

Essential, indeed.

friendly advice to a lot of young men, and a lot of old men, too

Go to Tibet.

Ride a camel.

Read the Bible.

Paint your shoes blue.

Grow a beard.

Circle the world in a paper canoe.

Subscribe to the Saturday Evening Post . Chew on the left side of your mouth only. Marry a woman with one leg and shave with a straight razor. And carve your name in her anus.

Brush your teeth with gasoline.

Sleep all day and climb trees at night.

Be a monk and drink buckshot and beer.

Hold your head under water and play the violin.

Do a belly dance before pink candles.

Kill your dog.

Run for mayor.

Live in a barrel.

Break your head with a hatchet.

Plant tulips in the rain.

But don’t write any more poetry.

To give life you must take life,

and as our grief falls flat and hollow

upon the billion-blooded sea

I pass upon serious inward-breaking shoals rimmed

with white-legged, white-bellied rotting creatures

lengthily dead and rioting against surrounding scenes.

Dear child, I only did to you what the sparrow

did to you; I am old when it is fashionable to be

young; I cry when it is fashionable to laugh.

I hated you when it would have taken less courage

to love.

Making love in the sun, in the morning sun

in a hotel room

above the alley

where poor men poke for bottles;

making love in the sun

making love by a carpet redder than our blood,

making love while the boys sell headlines

and Cadillacs,

making love by a photograph of Paris

and an open pack of Chesterfields,

making love while other men—poor

fools—

work.

That moment—to this . . .

may be years in the way they measure,

but it’s only one sentence back in my mind—

there are so many days

when living stops and pulls up and sits

and waits like a train on the rails.

I pass the hotel at 8

and at 5; there are cats in the alleys

and bottles and bums,

and I look up at the window and think,

I no longer know where you are, and I walk on and wonder where the living goes when it stops.

the next time you listen to Borodin

remember he was just a chemist

who wrote music to relax;

his house was jammed with people:

students, artists, drunkards, bums,

and he never knew how to say “no.”

the next time you listen to Borodin

remember his wife used his compositions

to line the cat boxes with

or to cover jars of sour milk;

she had asthma and insomnia

and fed him soft-boiled eggs

and when he wanted to cover his head

to hide out the sounds of the house

she only allowed him to use the sheet;

besides there was usually somebody

in his bed

(they slept separately when they slept

at all)

and since all the chairs

were usually taken

he often slept on the stairway

wrapped in an old shawl;

she told him when to cut his nails,

not to sing or whistle

or put too much lemon in his tea

or press it with a spoon;

Symphony #2 in B Minor Prince Igor In the Steppes of Central Asia he could sleep only by putting a piece of dark cloth over his eyes; in 1887 he attended a dance at the Medical Academy dressed in a merrymaking national costume; at last, he seemed exceptionally gay and when he fell to the floor, they thought he was clowning.

the next time you listen to Borodin,

remember . . .

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Читать дальше