A woman’s power was still to be feared; and like those new women, this universal sister’s tenets, intended to create an alternative clan, were not entirely welcome as they sundered families and married couples and separated children from parents. When a later visitor asked Mary Ann, ‘Why not procreate?’, she replied that the earth was already too full. Such sentiments echoed those of Reverend Malthus, who believed mankind was doomed if it continued to reproduce without check. But they also threatened the defining unit of an age which relied on reproduction. The family yoked the workers of the industrial revolution to the demands of capitalism; Mary Ann directly opposed that economic adhesion. For such a person of such a background and of such a sex to set up such a challenge was unacceptable. Mrs Girling made a travesty of her married name, and in the process became an anti-woman.

There were other reasons to fear Girlingism: it created tensions not just between families, but between communities. In an era of insecurity and high unemployment – exemplified by the agricultural strikes which hit East Suffolk in the early 1870s as the newly formed Agricultural Labourers’ Union clashed with the Farmers’ Association – men lost their jobs because of Mary Ann. In the market and barrack town of Woodbridge, her teachings began to concern clergy and upset landowners, anxious at her effect on their flocks and labour force: ‘Many of the males were discharged from their situations, and others suffered loss in a variety of ways’. To some it seemed they had lost their senses to religious mania, and were suitable subjects for the local lunatic asylum at Melton – an establishment of more than four hundred disturbed souls, their occupations, listed next to their initials in the 1871 census, representative of Mary Ann’s constituency: farm labourers and their wives; factory girls and seamen’s wives; soldiers and needlewomen; chimney sweeps and policemen’s wives; brush makers and lime burners; or simply, in the case of ‘V. F.’, a ‘loose character’.

They were the psychiatric casualties of an industrial era, the kind of minds susceptible to a woman who might have found herself similarly incarcerated. Or perhaps Mary Ann evoked an older belief, when people had laid votive offerings in the lakes and rivers, reaching down to that elemental world beneath their feet. Whatever the source of her power, it seemed there was a primal force gathering around this prophetess, one which would invoke spirits and provoke opposition. One man bet his friends that he would shoot Mary Ann on a certain night – although in the event the would-be assassin himself converted and became a Girlingite, a miracle taken by her followers as proof that their leader was protected by God. That which did not kill her made Mary Ann stronger, and in this sensational narrative – something between penny dreadful and missionary tract – she had become a symbolic, almost revolutionary figure.

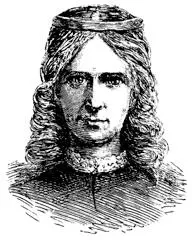

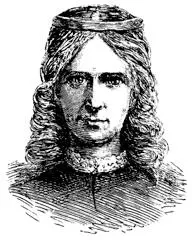

A later image of Mary Ann depicts her as an androgynous angel from some Renaissance woodcut, wearing indeterminate, anachronistic dress, her head encircled by a band in simple recognition of her sacred mission. Her stare challenges the viewer and imbues the portrait with the air of an icon. This idealised Mary Ann is far from what we know of her true features; more Joan of Arc as seen in a Victorian picturebook than the face of a farm labourer’s daughter. But equally, it could be an advertisement for the latest nostrum, lacking only the caption, Mother Girling Saves .

Girlingite meetings took a set form. Bible verses were read and debated, followed by prayer. But then came the strange dancing and trance-like speaking in tongues which Eliza Folkard had exhibited, and which were already attracting crowds. These shaking fits earned the sect the nickname Convulsionists, although they preferred to call themselves Children of God, from St John’s gospel, ‘… to all those who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God; who were born, not of blood nor of the will of flesh nor of the will of man, but of God’. Like the Corinthians in the wake of St Paul’s mission, they would ‘jabber and quake’ when in the spirit, led by Mary Ann herself, leaping from foot to foot while waving her arms as if beckoning while she exhorted the Lord’s name. To some these antics resembled the dance of a savage; others watching the ‘springy, elastic movements and considerable waving of her arms … could hardly resist the comic aspect of the scene’.

Soon enough these rites attracted the attention of the press, and on 20 April 1871 a headline appeared in the Woodbridge Reporter & Aldeburgh Times :

MOBBING A FEMALE PREACHER.

The accompanying story may have been the first occasion on which Mary Ann’s name appeared in print; it was certainly not the last.

Reporting on a case heard at the Framlingham Petty Sessions by F. S. Corrance, the local Member of Parliament, and two clergymen – the Reverends G. F. Pooley and G. H. Porter – the newspaper gave details of five young men, William Goldsmith, James George, Samuel Crane, James Nichols and John Barham, who were charged by a farmer with ‘riotous behaviour in his dwelling, which is registered as a place for religious worship’.

At first it seemed a matter of mere youthful high spirits. The farmer, forty-eight-year-old Leonard Benham of Stratford St Andrew, worked 138 acres – belonging to the Earl of Guildford – where he employed three men and a boy, as well as two household servants (one of them being twenty-year-old William Folkard, a kinsman of Eliza’s). But Benham was also a member of the Children of God, and had resolved to support Mary Ann ‘at any cost’. He would pledge his entire family – his wife Martha, forty; his daughters Ellen, twenty, Emma, thirteen, and Mary Ann, then four years old; together with his sons Arthur, then aged sixteen, William, fifteen, and George, just five – to the cause.

That Sunday afternoon, a meeting had been held in Benham’s house which was attended by the five defendants – not by invitation. As the Girlingites prayed, one of the young men, John Barham, began to talk and laugh. When asked to be quiet, he replied by singing and hallooing, with his friends joining in.

‘I went to the door and stood near them,’ Leonard Benham told the court. ‘They said, “Take your sins off your own back, we won’t believe you, you’re a liar.” I told them mine was a registered house. They told me not to daubt them up with untempered mortar’ – an obscure metaphor which would pursue the Girlingites, along with mobs hurling slack, or slaked lime.

The hooligans then began pulling off his wallpaper, and declared that ‘they would be d—if they wouldn’t kiss Mrs Girling before they left’. Failing in this, they tried to kiss another member of the congregation, Robert Spall. ‘Not being able to do that, they said they would kiss Mrs Spall, but did not attempt to do it.’

That night the gang came back to finish what they’d started. ‘What a pity it is you young men come here and make a disturbance,’ Benham told them. ‘The law is very stringent about this, and you’ll hear something from me about it.’ But Nichols strode into the room and began shouting and stamping, while Goldsmith mockingly held up a stick to which he’d attached a red handkerchief, saying, ‘This is a flag of distress.’ He then began to declaim a text of his own, and sat down to light his pipe. Crane, also smoking, cried, ‘Pinpatches and sprats at three pence a quarter.’ The scene turned violent as the gang began to break up the furniture, with Barham sitting on the window-sill shouting, ‘My wife has run away with a man that has three children, and when she comes back I’ll be d—if I have her again.’

Читать дальше