In this way Paracelsus initiated a new study he called ‘iatrochemistry’, which invoked chemistry to the aid of medicine. Whereas the Paracelsians were individualistic in their pantheistic interpretation of Nature, regarding chemical knowledge as incommunicable except between and through the inspiration proper to a magus, Libavius and the textbook writers who followed him argued that chemistry could be learned by all in the classroom, provided it was put into a methodical form. This construction of a pedagogical discipline involved the classification of laboratory techniques and operations and the establishment of a standardized language of chemical substances. Progress in chemistry, or in any science, would come only from a collective endeavour to combine the subjective, and possibly unreliable, contributions of individuals after subjecting them to peer review and measuring each one critically against past wisdom and experience.

Iatrochemical doctrines became extremely popular during the seventeenth century, and not unlinked with this was a rise in the social status of the apothecary. Both in Britain and on the Continent there was a compromise in which chemical remedies were adopted without commitment to the Paracelsian cosmology. Didactically acquired knowledge of iatrochemistry gave these medical practitioners (who in Britain were to become the general practitioners of the nineteenth and twentieth century) a base upon which they could branch out into their own medical practice and away from the control of university-educated physicians. The need for self-advertisement encouraged them to teach iatrochemical practice and to introduce inorganic remedies into the pharmacopoeia. They were therefore less secretive than the alchemists. Because they wanted to find and prepare useful medical remedies, they were keen to know how to recognize and prepare definite chemical substances with repeatable properties. In teaching their subject, what was wanted was a good textbook, which would provide clear and simple recipes for the preparation of their drugs, with clear unambiguous names for their substances and adequate instructions on the making and use of apparatus for the preparations. Theory could play second fiddle to practice.

Iatrochemistry became very much a French art and here the subject was helped in Paris by the existence of chemical instruction at the Jardin du Roi. Beginning with Jean Beguin’s Tyrocinium Chymicum in 1610, which plagiarized a good deal from Libavius’ Alchemia , each successive professor, Étienne de Clave, Christopher Glaser and Nicholas Lemery, composed a textbook for the instruction of the apothecary’s apprentices who flocked to their annual lectures. Many of these texts went into other languages, including Latin and English. By 1675, when Lemery published his Cours de Chimie , a textbook tradition had been firmly established as part of didactic chemistry and which considerably aided the establishment of chemistry as a discipline. Some historians of chemistry believe that this formulation of chemistry as a scholarly, didactic discipline, which began with Libavius well before the establishment of the mechanical philosophy, was far more significant than the latter for the creation of modern chemistry.

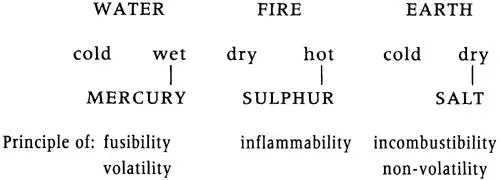

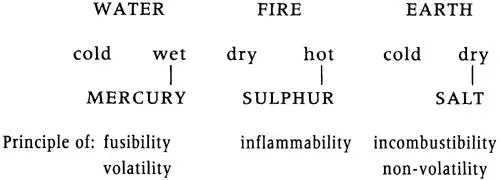

In chemical theory, Paracelsus introduced the doctrine of the tria prima , or the three principles. Medical substances, he said, were ultimately composed from the four Aristotelian elements, which formed the receptacles or matrices for the universal qualities of a trinity of primary bodies he called salt (body), sulphur (soul) and mercury (spirit).

The world is as God created it. He founded this primordial body on the trinity of mercury, sulphur and salt and these are the three substances of which the complete body consists. For they form everything that lies in the four elements, they bear them all the forces and faculties of perishable things.

The doctrine of the tria prima was clearly an extension of the Arabic sulphur – mercury theory of metals applied to all materials whether metallic, non-metallic, animal or vegetable, and given body by the addition of a third principle, salt.

This theory of composition, which essentially explained gross properties by hypothetical property-bearing constituents, rapidly replaced the old sulphur – mercury theory, though not the Aristotelian four elements. Paracelsus was happy to use Aristotle’s example of the analysis of wood by destructive distillation to justify the tria prima theory. Smoke was the volatile portion, mercury; the light and glow of the fire demonstrated the presence of sulphur; and the incombustible, non-volatile ash remaining was the salt. Water was included within the mercury principle, which explained the cohesion of bodies.

Van Helmont begged to differ and provided a simpler, and supposedly more empirical, alternative theory of composition.

Iatrochemistry came to fruition in the work of a Flemish nobleman, Joan-Baptista van Helmont (1577–1644). Present-day Belgium was then under Spanish control. In 1625, as a consequence of Helmont’s controversial advocation of ‘weapon salve’ treatment in which a weapon, and not a wound, was treated, he was denounced as a heretic by the Spanish Inquisition and spent the remainder of his life, like Galileo, under house arrest. As with Paracelsus, it was van Helmont’s posthumous writings that brought his name to fame and exerted a considerable influence upon seventeenth-century natural philosophers like Boyle and Newton. This influence was firmly established after 1648 with the posthumous publication of his Ortus Medicinae , which was issued in English in 1662 as Oriatricke or Physick Refined. Helmont, who claimed to have witnessed a successful transmutation of a base metal into gold, was a disciple of Paracelsus and an iatrochemist. However, like any good disciple, he modified, interpreted and disagreed with his master’s doctrines considerably.

After studying several areas of natural philosophy, he chose medicine and chemistry for his career, calling himself a ‘philosopher by fire’. He was strongly anti-Aristotelian, one facet of which was that he refused to accept the four-element theory. But neither was he able to accept Paracelsus’ tria prima. To simplify a rather complex philosophy, we can say that according to van Helmont there were two first beginnings of bodies: water and an active, organizing principle, or ‘ferment’, which moulded the various forms and properties of substances. This return to a unitary theory of matter was influenced by his interpretation of Genesis, for water, together with the heavens and the earth, had been formed on the first day.

In more detail, he imagined that there were two ultimate elements, air and water. Air was, however, purely a physical medium, which did not participate in transmutations, whereas water could be moulded into the rich variety of substances found on the earth. Van Helmont did not consider fire to be a material element, but a transforming agent. As for earth, from his experimental observations, he believed that this was created by the action of ferments upon water.

The first beginnings of bodies, and of corporeal causes, are two, and no more. They are surely the element water, from which bodies are fashioned, and the ferment.

As we have already seen in the introduction, the justification for this belief was an interesting, quantitative growth experiment with a young willow tree. Additional supporting evidence came from the fact that fish were nourished ‘solely’ by water, that seashells were found on dry land, and that solid bodies could be transformed into ‘savoury waters’, that is, into solution. In the latter case, Helmont took a weighed amount of sand, and fused it with excess alkali to form water-glass, which liquefied on standing in air. Here was a palpable demonstration of the reconversion of earth back into water. More remarkably, this ‘water’ could be reconverted back to ‘earth’ by treatment with acid, when the silica sand recovered was found to have the same weight as the starting material.

Читать дальше