The author on a destroyed Soviet tank, near Kandahar, 1988.

Our destination was Abdul Razzak’s secret training camp cum madrassa or religious school in an area called Khunderab, inside a narrow gorge hidden by overhanging mountains, the entrance blasted out of the rock with dynamite. A guard sat at a table, an old black telephone in front of him. Abdul Razzak explained it was part of a wireless phone system captured from the Russians, and enabled camp-guards to call a military post on top of the mountains where they had men stationed with anti-aircraft guns if an enemy approached.

The camp, which acted as a training and rest camp for fighters for the Mullahs Front, had existed for about a year, moving there after the previous site was bombed by Soviet Mig 17s for seventy-four hours continuously, destroying all their weapons and killing fifty men. ‘There were forty planes dropping 3000 bombs,’ said one man with what I presumed was the usual Afghan exaggeration of multiplying everything by ten, ‘it was the only day we couldn’t pray.’

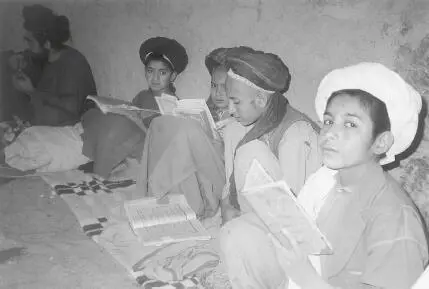

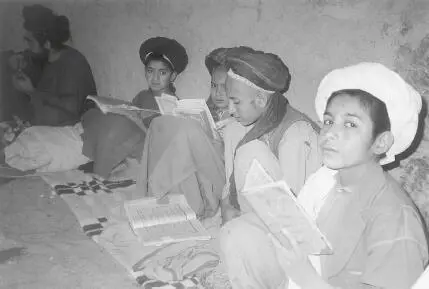

Prayer was an important feature of camp-life. The camp was home to eighty men and forty-two students aged from eight to eighteen and Abdul Razzak took me to see the school where children studied the Koran and Arabic. We watched a recitation lesson, boys rocking back and forth as they intoned the words of the Koran, and Abdul Razzak gave some religious books he had brought from Quetta to the white-bearded teacher. Hamid told me that for boys educated in madrassas , the rocking becomes such a habit that later in life they cannot read without it. Had we but known it, we were seeing the incipient Taliban. In my diary I wrote: ‘Mohammed Jan is eight. After Koranic lessons he learns how to load a BM12’.

Next we saw the boys’ dormitory – camouflaged from above with a roof of tree branches and hay that allowed air to circulate, keeping it cool inside. A small boy sat in the doorway cleaning a pile of Kalashnikovs. There seemed to be weaponry everywhere. ‘We have thirty-five RPG7, forty-two RR82mm recoil rifles, seven anti-aircraft guns,’ said Razzak. They also had two Stinger missiles left of an initial six which they received in November 1987, kept under twenty-four-hour guard, though they happily took them out to pose for photographs. Nine hundred of these heat-seeking missiles had been provided by the Americans to the resistance in 1986–7 along with British Blowpipes and were thought to have turned the tide of the war by countering the threat of Soviet air superiority though many were instead sold on to Iran, forcing the CIA to launch a buyback programme which did not stop them later turning up everywhere from Angola to Algeria.

The camp was run by Abdul Razzak’s friend Khadi Mohammed Gul who said he was twenty-eight but looked at least ten years older. He told me he had wanted to be a mullah, a village priest, but had joined the resistance and in 1983 been captured by the Soviets and sent to Pul-i-Charki, the notorious prison on the outskirts of Kabul. Run by KHAD, the East-German trained Afghan secret police, it held around 10,000 political dissidents. He was there for four years until he was released in a prisoner swap when Razzak captured a top commander from the Afghan regime.

Survivors of Pul-i-Charki were rare and I asked him about life there. ‘We knew whenever the Soviets had suffered heavy casualties because they would take a whole lot of prisoners, remove their blood for transfusions then shoot them,’ he said. He also told of awful tortures. ‘Sometimes it would be electric shocks to the nose, ears, teeth and genitals, so many that now I am impotent. Other times they tied us to trees with our feet on broken glass and left us for several days until the wounds went rotten and there were maggots inside. Another punishment was to give us food with laxative or something bad in to cause diarrhoea then leave us in a room one meter square so we would have to live in our own excreta for days. Sometimes at night they would call someone’s name and we would know he was being shot but we would say “bye!” as if he was going for a trip but we knew he’d never come back.’

The words hung heavily in the air and we sat there for a while in silence. Then I asked to see the rest of the camp. There was a clinic with a few lint bandages and a box of aspirins where a doctor was cleaning a horrible suppurating wound on the thigh of a fighter who sat silently despite the agonising treatment, and a bakery where young boys were slapping flat wide oblongs of dough onto the wall of a large clay pot buried in the ground with hot coals in the bottom to make nan , the traditional unleavened bread. Some other boys were scrubbing clothes in the small river and it was hard not to notice the red staining the water. A few goats and sheep were grazing and there was a small plantation of okra or ladyfingers as well as several apple trees so the camp was more or less self-sufficient.

The camp had strict rules, one of which was ‘men must be taught religious teachings as much as possible’. Everyone was checked at the gate and there were heavy penalties for sneaking out weapons or ammunition. 3 ‘You see we are not like those other groups which steal the money and sell the arms to the Iranians,’ said Gul. ‘This is what jihad is meant to be.’ He pointed out that many villagers used the clinic, which was the only medical facility for perhaps fifty miles, and all wanted their boys to be accepted to study at the school as free board was provided.

It was the first time I had seen a mujaheddin group making an effort to provide facilities to civilians. At the main gate as we were leaving, an exhausted ten-year-old boy named Safa Mohammed had just arrived ‘to join the resistance’ after a fourteen-hour walk through the mountains. ‘My father was killed by the Russians and I ran away from my mother,’ he said. ‘First I want to study but when I grow up I will carry a gun and kill Soviets.’

It was evening as we drove away, bumping across rutted mountain tracks, headlights off to avoid being spotted by a Russian plane. The area was heavily mined so two brave men walked in front of the wheels of the jeeps, testing the ground as we followed slowly behind. Of all the many ways to die or be injured in Afghanistan, mines were the scariest. The Soviets had scattered them everywhere, including what the mujaheddin called jumping mines, designed to bounce up and explode in the genitals, and even some disguised as pens and dolls to entice children. Most were butterfly mines dropped from the air, which maimed rather than killed and thus took out more resistance firepower as men would be needed to carry the victim. No one knew how many mines there were – the latest figure from the US State Department was more than ten million – nor their whereabouts, for contrary to all rules of warfare the Soviets had not kept maps.

I had seen far too many victims in the hospitals of Peshawar with legs or arms blown off, eyes missing or guts hanging out, as well as all the people in the bazaars and refugee camps with stumps for limbs and had taken to identifying interviewees in my notebooks as ‘man with beard and two eyes’. My head throbbed from concentrating as I scoured the land in front for mines and scanned the skies, for somewhere among the many stars there might be a Soviet Mig.

It was 2.30 a.m. when we arrived at our destination of Argandab, a valley of orchards about ten miles west of Kandahar which Alexander the Great had used as a camp for his army of 30,000 men and elephants and was now an important base of the resistance. Mujaheddin love gadgets and someone turned on flashing fairy lights to herald our arrival after all our efforts to be invisible. The rumble of guns was not far off but I fell asleep to the soothing sound of running water from a river.

Читать дальше