William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2015

Copyright © Christina Lamb 2015

Christina Lamb asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

Cover photograph: Justin Sutcliffe

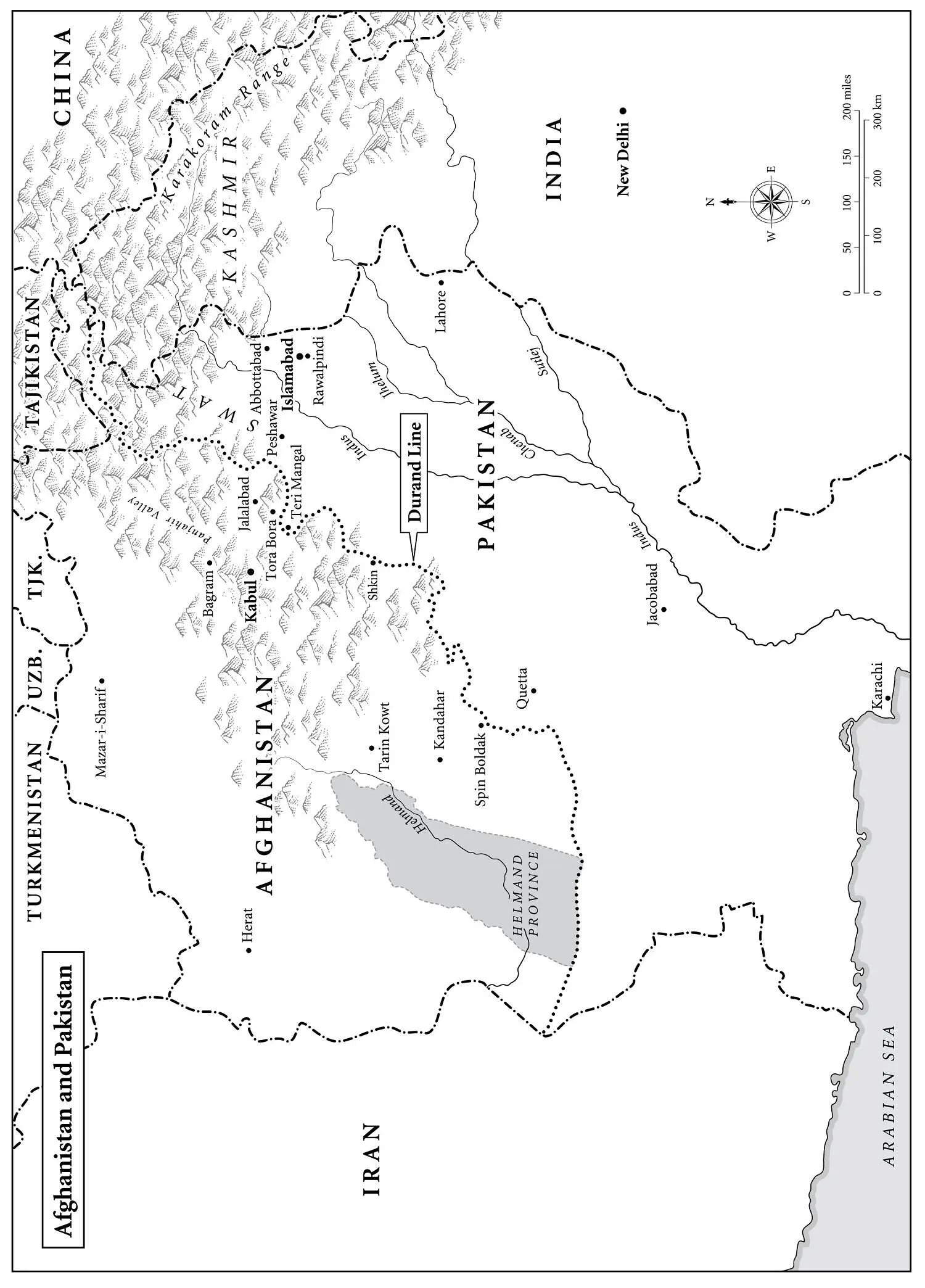

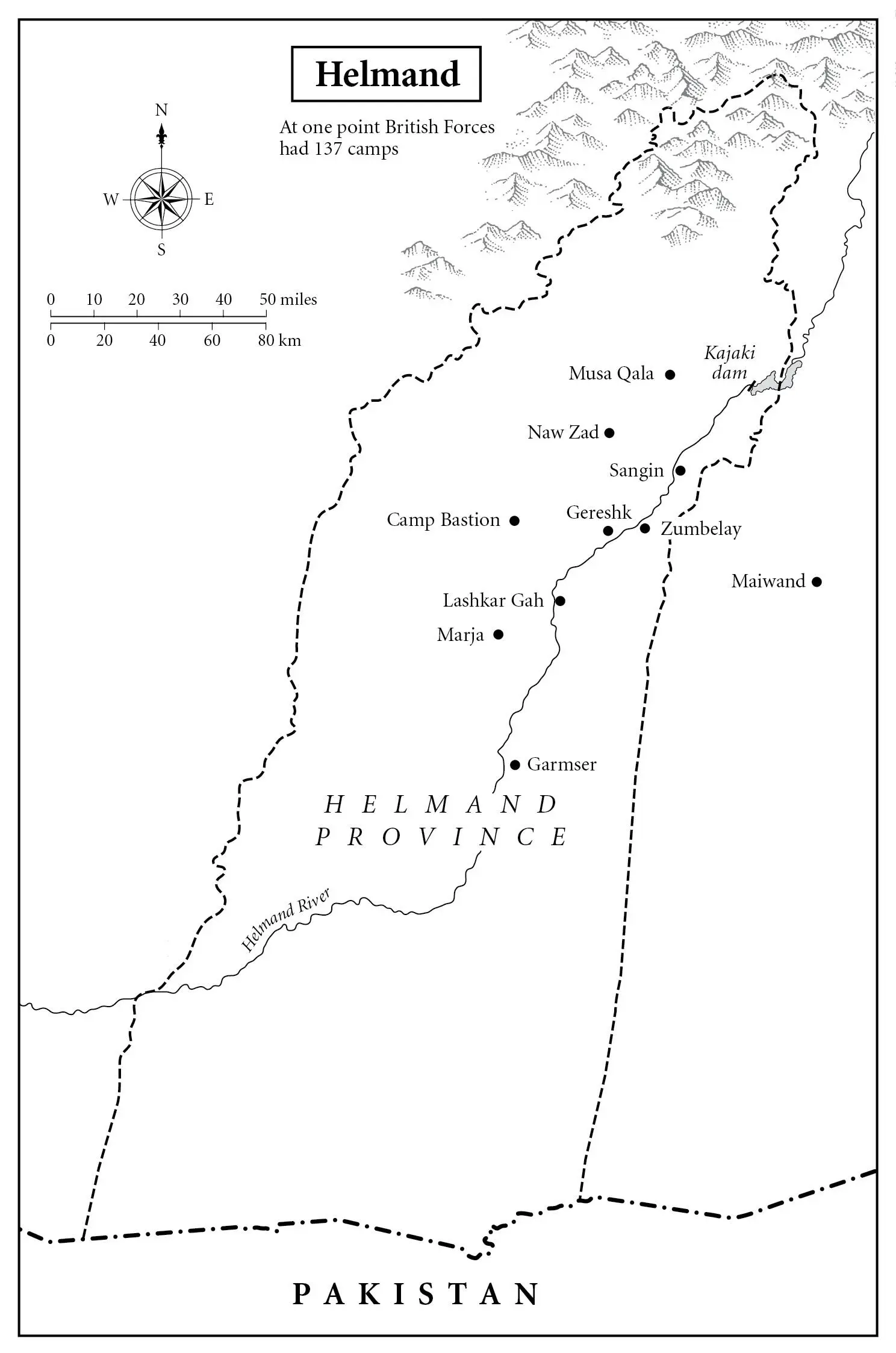

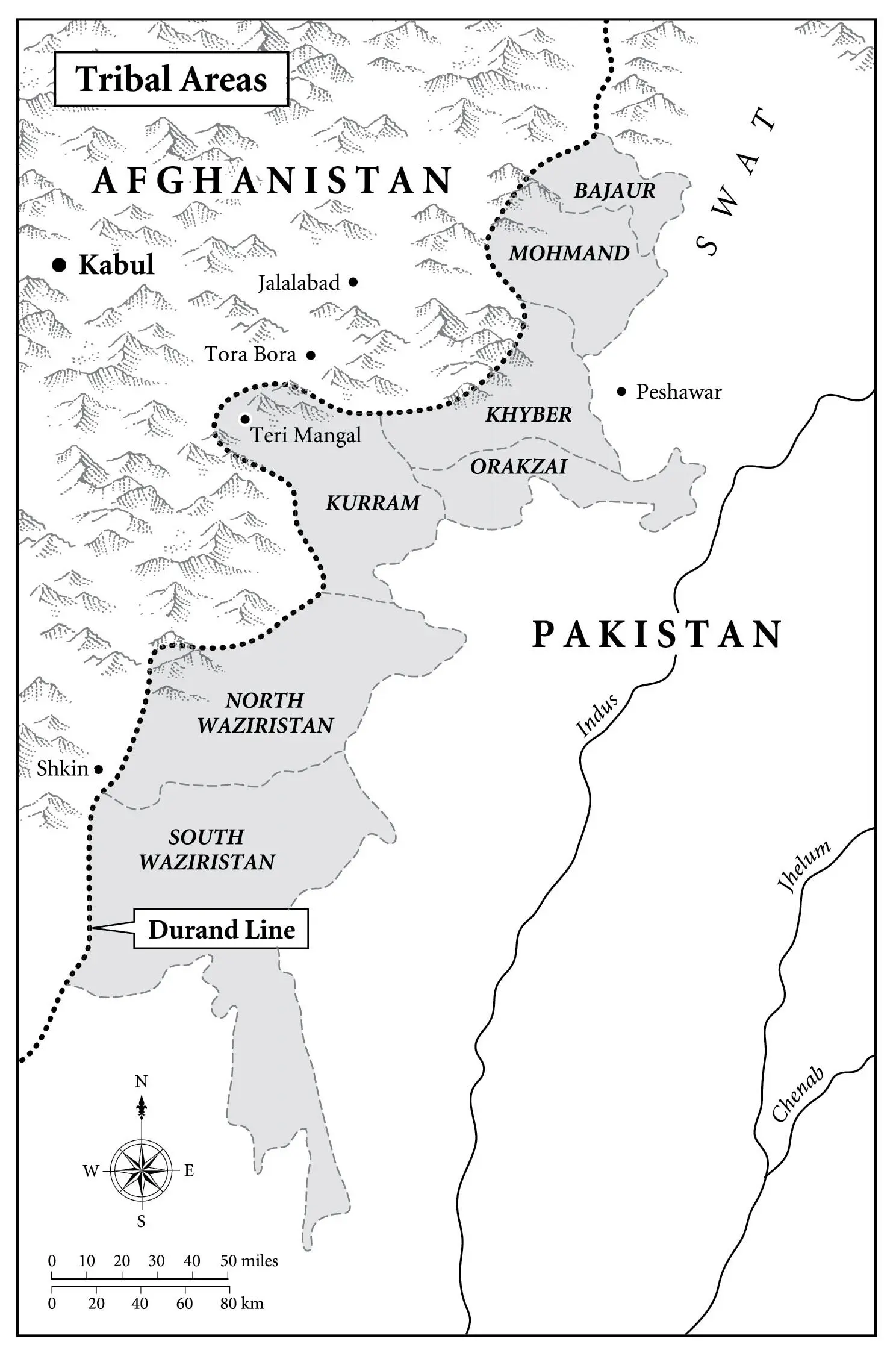

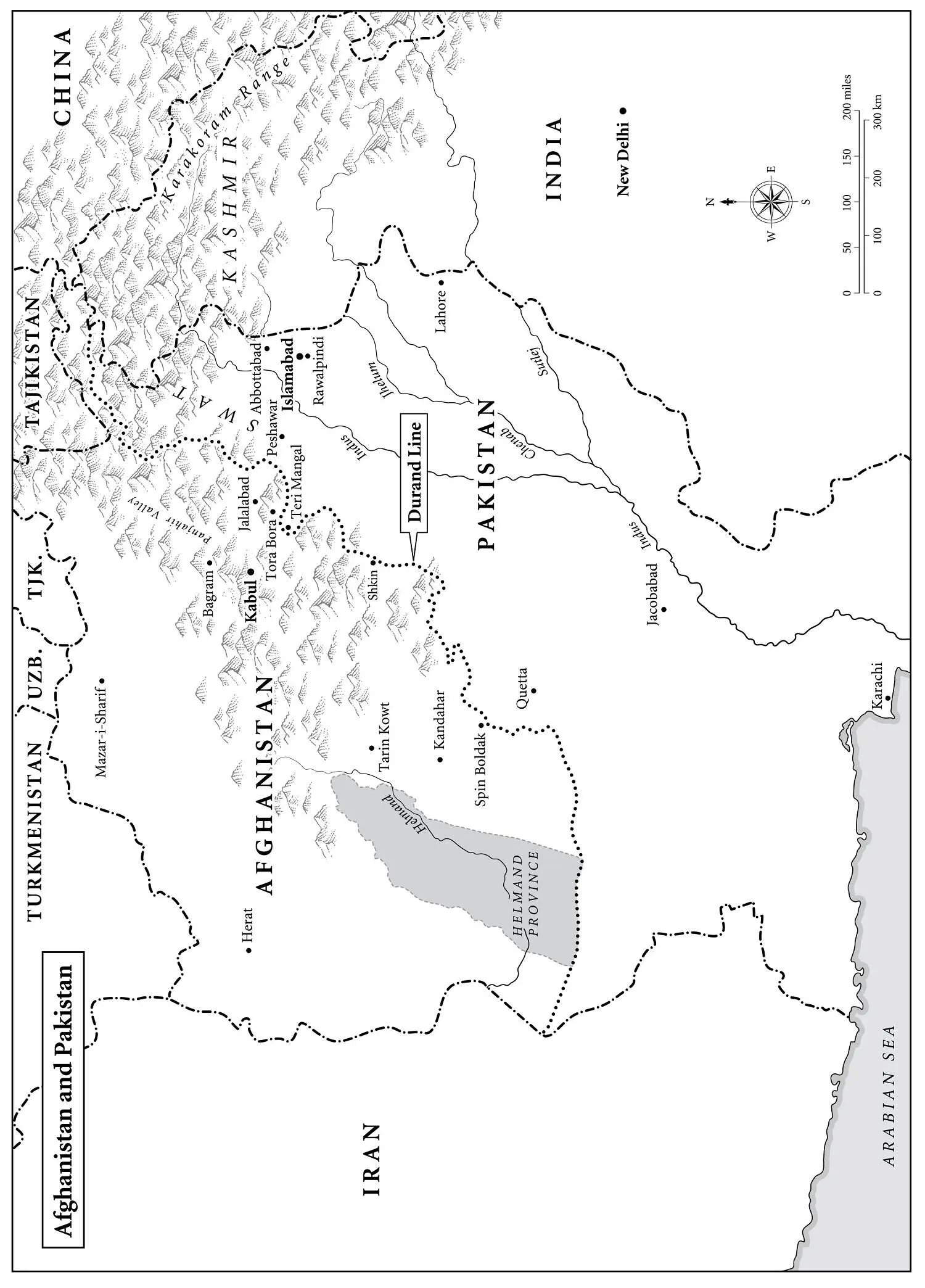

Maps by John Gilkes

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007256921

Ebook Edition © April 2015 ISBN: 9780008171278

Version: 2016-03-18

In memory of all those who lost their lives to terrorism – or fighting it – from New York to London to Kandahar to Peshawar

It is fatal to enter any war without the will to win it.

General Douglas MacArthur

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Maps

The Leaving

PART 1: GETTING IN

1 Rule Number One

2 Sixty Words

3 Making – and Almost Killing – a President

4 Ground Zero

5 Losing bin Laden – the Not So Great Escape

6 A Tale of Two Generals

7 Taliban Central

8 Merchants of Ruin – the Return of the Warlords

9 Theatre of War

10 A Tale of Two Wars

11 Voting With Mullah Omar

PART II: WAR

12 Ambush

13 Bringing Dolphins to Helmand

14 Tethered Goats

15 The President in His Bloody Palace

16 Whose Side Are You On?

17 The Snake Bites Back

18 The Weathermen of Kandahar

19 We’ll Always Have Kabul

20 Death of a Poet

21 Meeting Colonel Imam

PART III: THE GOOD WAR

22 The View From Washington

23 All About the Politics

24 The Butcher of Mumbai

25 Losing the Moral High Ground in Margaritaville

26 Chairman Mullen and the Cadillac of the Skies

PART IV: GETTING OUT

27 Killing bin Laden

Postscript: War Never Leaves You

Appendix: The Costs of War

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Notes

Select Bibliography

Index

Also by Christina Lamb

About the Author

About the Publisher

Camp Bastion, Helmand, 26–27 October 2014

‘Ladies and gentlemen, please take your seats for the End of Operations Ceremony!’ The American voice boomed enthusiastically over the speakers as if it were the drum roll for a sporting event.

Rows of grey fold-up chairs had been arranged facing a large blast wall painted with murals marking each of the last few commands in Helmand. In front of the wall two detachments of US Marines and British troops stood to attention, flanked on either side by Afghan soldiers, who had been instructed beforehand not to hold hands. Above flew four flags – the Union Jack, the Stars and Stripes, and those of NATO and Afghanistan.

A padre read some Koranic verses, then three American generals took turns at the plinth to speak. One of them was the last commander in Helmand, Brigadier General D.D. Yoo of the US Marines, a man of Napoleonic stature both in height and personality who took the mike from the lectern to strut in front of the audience as if about to burst into song.

Phrases from the speakers, each as determinedly upbeat as the announcer, swam in the hot air like speech bubbles. No one spoke of defeat, or retreat, or withdrawal in the face of an intransigent enemy, or of publics and politicians back home who could take no more flag-draped coffins.

‘This transfer is a sign of progress,’ said Brigadier General Yoo. ‘It is not about the coalition. It is really about the Afghans and what they have achieved over the last thirteen years.’

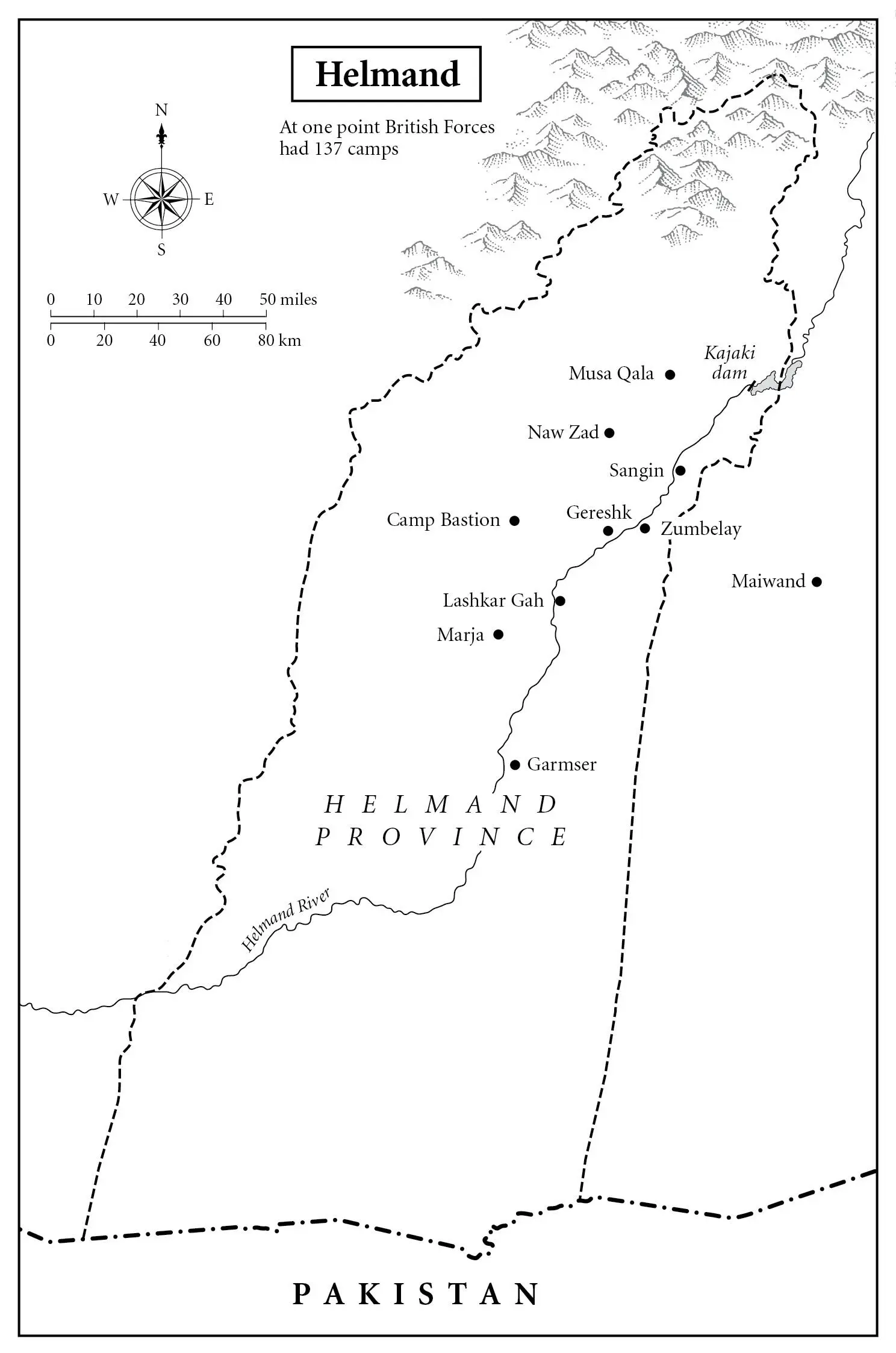

Helmand would now be under control of Afghan forces, commanded by Major General Sayed Malouk. ‘We are ready,’ Malouk insisted, even though he didn’t quite look me in the eye as he said it. He had already lost almost eight hundred men that fighting season, and had himself narrowly escaped a roadside bomb in Sangin.

No British officer spoke, and Britain’s eight-year role in Helmand garnered barely a mention, which seemed odd, for this had been the country’s longest war in modern times, and its hardest fighting for more than half a century.

The hot sun beat down and guests swigged from bottles of mineral water as ‘God Save the Queen’ and ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ were played and the flags were lowered. The Union Jack was carefully folded, and handed to Brigadier Rob Thomson, the last British commander. Only the Afghan flag was left fluttering as Camp Bastion came under Afghan command, and Britain’s fourth war in Afghanistan officially came to an end.

Guests were taken into a cabin where a banquet lunch of smoked salmon, slow-cooked beef and chocolate fudge cake had been specially flown in. The genial Afghan army chief General Sher Mohammad Karimi presented Brigadier General Yoo with a commemorative certificate and a carpet, and both sides took souvenir photographs. It all seemed surreal.

I felt tears stinging my face. Four hundred and fifty-three British soldiers had been lost in Afghanistan, of whom 404 died in Helmand, many of them young enough to be my son. Hundreds more had lost limbs to roadside bombs or been mentally scarred for life. Tens of thousands of Afghans had lost relatives or homes, and I had met many Helmandis living as refugees in a camp in Kabul, begging for scraps of dry bread and meat fat, and burying children in the mornings who had frozen to death overnight in the winter cold.

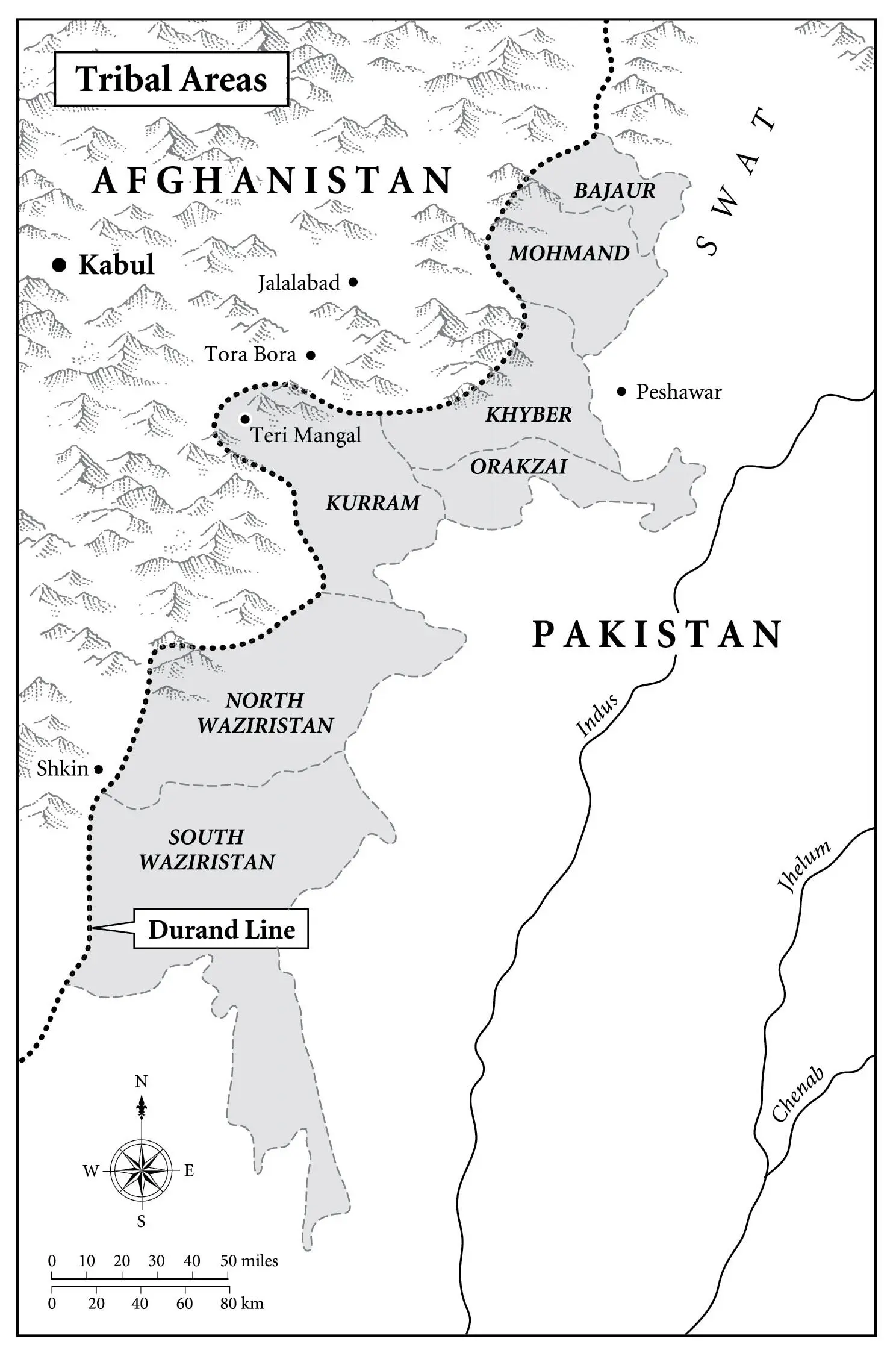

Watching the flag come down felt like the end of everything. This fierce, turtle-shaped country had been part of my entire adult life, longer than any relationship or job. It was twenty-seven years since I’d first come to Afghanistan as a young wannabe foreign correspondent, crossing the Hindu Kush with the mujaheddin fighting the Russians, and falling unequivocally in love with this land of pomegranates and war. I’d had narrow escapes in muddy fields nearby, both with those mujaheddin who went on to become Taliban, and then with British soldiers fighting those Taliban. My first big assignment was covering the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, and never in my wildest dreams had I imagined I would be back a quarter of a century later, covering my own country’s ignominious departure. Just as after the Russians had gone, everyone had lost interest in Afghanistan, now Western troops were leaving I wondered if anyone would care.

Читать дальше