The Cariboo Trail: A Chronicle of the Gold-fields of British Columbia by Agnes Christina Laut

Literary Thoughts Edition presents

The Cariboo Trail: A Chronicle of the Gold-fields of British Columbia

by Agnes Christina Laut

Transscribed and Published by Jacson Keating (editor)

For more titles of the Literary Thoughts edition, visit our website: www.literarythoughts.com

All rights reserved. No part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, copied in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise transmitted without written permission from the publisher. You must not circulate this book in any format. For permission to reproduce any one part of this edition, contact us on our website: www.literarythoughts.com.

This edition is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. It may not be resold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Amazon and purchase your own copy of the ISBN edition available below. Thank you for respecting the efforts of this edition.

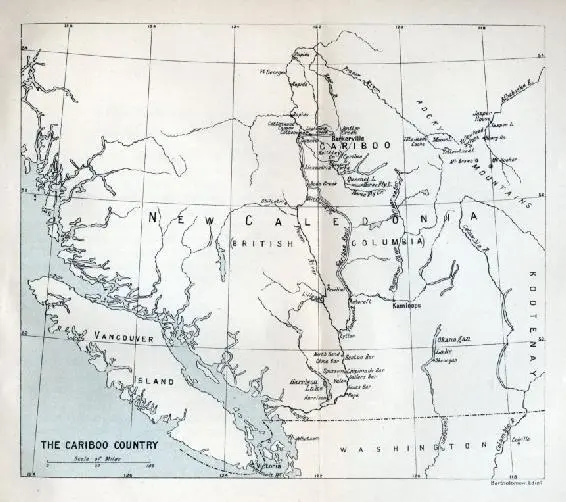

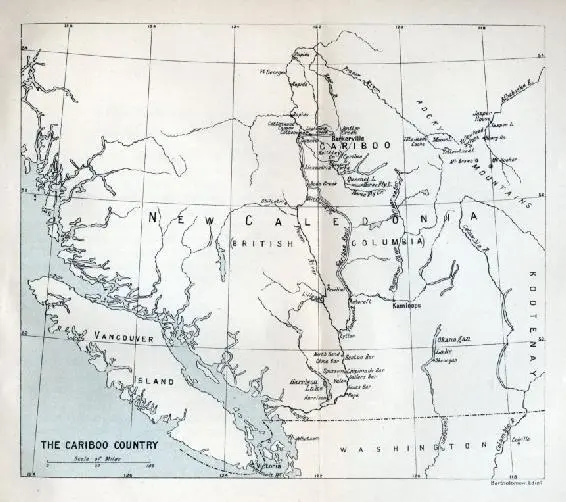

Map of the Cariboo Country

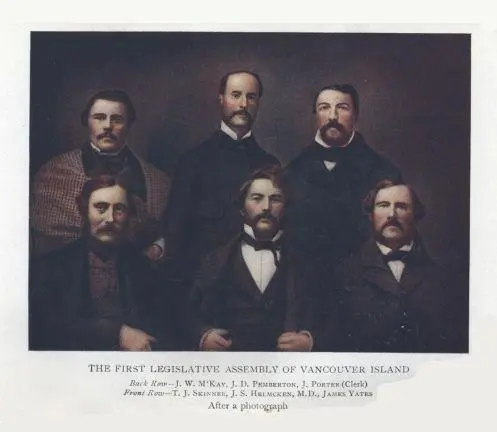

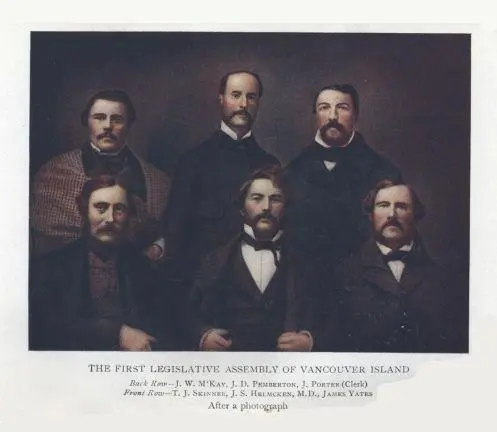

The first Legislative Assembly of Vancouver Island

Back Row—J. W. M'Kay, J. D. Pemberton, J. Porter (Clerk)

Front Row—T. J. Skinner, J. S. Helmcken, M. D., James Yates

(After a Photograph)

CHAPTER I – THE 'ARGONAUTS'

Early in 1849 the sleepy quiet of Victoria, Vancouver Island, was disturbed by the arrival of straggling groups of ragged nondescript wanderers, who were neither trappers nor settlers. They carried blanket packs on their backs and leather bags belted securely round the waist close to their pistols. They did not wear moccasins after the fashion of trappers, but heavy, knee-high, hobnailed boots. In place of guns over their shoulders, they had picks and hammers and such stout sticks as mountaineers use in climbing. They did not forgather with the Indians. They shunned the Indians and had little to say to any one. They volunteered little information as to whence they had come or whither they were going. They sought out Roderick Finlayson, chief trader for the Hudson's Bay Company. They wanted provisions from the company—yes—rice, flour, ham, salt, pepper, sugar, and tobacco; and at the smithy they demanded shovels, picks, iron ladles, and wire screens. It was only when they came to pay that Finlayson felt sure of what he had already guessed. They unstrapped those little leather bags round under their cartridge belts and produced in tiny gold nuggets the price of what they had bought.

Finlayson did not know exactly what to do. The fur-trader hated the miner. The miner, wherever he went, sounded the knell of fur-trading; and the trapper did not like to have his game preserve overrun by fellows who scared off all animals from traps, set fire going to clear away underbrush, and owned responsibility to no authority. No doubt these men were 'argonauts' drifted up from the gold diggings of California; no doubt they were searching for new mines; but who had ever heard of gold in Vancouver Island, or in New Caledonia, as the mainland was named? If there had been gold, would not the company have found it? Finlayson probably thought the easiest way to get rid of the unwelcome visitors was to let them go on into the dangers of the wilds and then spread the news of the disappointment bound to be theirs.

He handled their nuggets doubtfully. Who knew for a certainty that it was gold anyhow? They bade him lay it on the smith's anvil and strike it with a hammer. Finlayson, smiling sceptically, did as he was told. The nuggets flattened to a yellow leaf as fine and flexible as silk. Finlayson took the nuggets at eleven dollars an ounce and sent the gold down to San Francisco, very doubtful what the real value would prove. It proved sixteen dollars to the ounce.

For seven or eight years afterwards rumours kept floating in to the company's forts of finds of gold. Many of the company's servants drifted away to California in the wake of the 'Forty-Niners,' and the company found it hard to keep its trappers from deserting all up and down the Pacific Coast. The quest for gold had become a sort of yellow-fever madness. Men flung certainty to the winds and trekked recklessly to California, to Oregon, to the hinterland of the country round Colville and Okanagan. Yet nothing occurred to cause any excitement in Victoria. There was a short-lived flurry over the discovery in Queen Charlotte Islands of a nugget valued at six hundred dollars and a vein of gold-bearing quartz. But the nugget was an isolated freak; the quartz could not be worked at a profit; and the movement suddenly died out. There were, however, signs of what was to follow. The chief trader at the little fur-post of Yale reported that when he rinsed sand round in his camp frying-pan, fine flakes and scales of yellow could be seen at the bottom.[1] But gold in such minute particles would not satisfy the men who were hunting nuggets. It required treatment by quicksilver. Though Maclean, the chief factor at Kamloops, kept all the specks and flakes brought to his post as samples from 1852 to 1856, he had less than would fill a half-pint bottle. If a half-pint is counted as a half-pound and the gold at the company's price of eleven dollars an ounce, it will be seen why four years of such discoveries did not set Victoria on fire.

It has been so with every discovery of gold in the history of the world. The silent, shaggy, ragged first scouts of the gold stampede wander houseless for years from hill to hill, from gully to gully, up rivers, up stream beds, up dry watercourses, seeking the source of those yellow specks seen far down the mountains near the sea. Precipice, rapids, avalanche, winter storm, take their toll of dead. Corpses are washed down in the spring floods; or the thaw reveals a prospector's shack smashed by a snowslide under which lie two dead 'pardners.' Then, by and by, when everybody has forgotten about it, a shaggy man comes out of the wilds with a leather bag; the bag goes to the mint; and the world goes mad.

Victoria went to sleep again. When men drifted in to trade dust and nuggets for picks and flour, the fur-traders smiled, and rightly surmised that the California diggings were playing out.

Though Vancouver Island was nominally a crown colony, it was still, with New Caledonia, practically a fief of the Hudson's Bay Company. James Douglas was governor. He was assisted in the administration by a council of three, nominated by himself—John Tod, James Cooper, and Roderick Finlayson. In 1856 a colonial legislature was elected and met at Victoria in August for the first time.[2] But, in fact, the company owned the colony, and its will was supreme in the government. John Work was the company's chief factor at Victoria and Finlayson was chief trader.

Because California and Oregon had gone American, some small British warships lay at Esquimalt harbour. The little fort had expanded beyond the stockade. The governor's house was to the east of the stockade. A new church had been built, and the Rev. Edward Cridge, afterwards known as Bishop Cridge, was the rector. Two schools had been built. Inside the fort were perhaps forty-five employees. Inside and outside lived some eight hundred people. But grass grew in the roads. There was no noise but the church bell or the fort bell, or the flapping of a sail while a ship came to anchor. Three hundred acres about the fort were worked by the company as a farm, which gave employment to about two dozen workmen, and on which were perhaps a hundred cattle and a score of brood mares. The company also had a saw-mill. Buildings of huge, squared timbers flanked three sides of the inner stockades—the dining-hall, the cook-house, the bunk-house, the store, the trader's house. There were two bastions, and from each cannon pointed. Close to the wicket at the main entrance stood the postoffice. Only a fringe of settlement went beyond the company's farm. The fort was sound asleep, secure in an eternal certainty that the domain which it guarded would never be overrun by American settlers as California and Oregon had been. The little Admiralty cruisers which lay at Esquimalt were guarantee that New Caledonia should never be stampeded into a republic by an inrush of aliens. Then, as now, it was Victoria's boast that it was more English than England.

Читать дальше