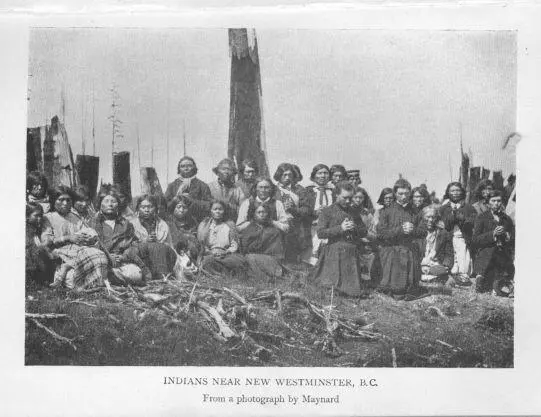

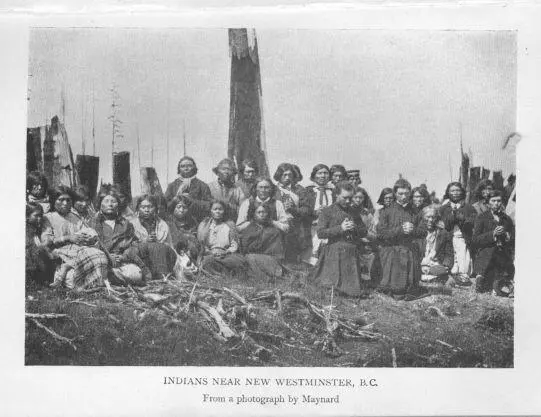

Indians near New Westminster, B.C. From a photograph by Maynard.

Within two miles of Yale eighty Indians and thirty white men were working the gold-bars; and log boarding-houses and saloons sprang up along the river-bank as if by magic. Naturally, the last comers of '58 were too late to get a place on the gold-bars, and they went back to the coast in disgust, calling the gold stampede 'the Fraser River humbug.' Nevertheless, men were washing, sluicing, rocking, and digging gold as far as Lillooet. Often the day's yield ran as high as eight hundred dollars a man; and the higher up the treasure-seekers pushed their way, the coarser grew the gold flakes and grains. Would the golden lure lead finally to the mother lode of all the yellow washings? That is the hope that draws the prospector from river to stream, from stream to dry gully bed, from dry gully to precipice edge, and often over the edge to death or fortune.

Exactly fifty-six years from the first rush of '58 in the month of April, I sat on the banks of the Fraser at Yale and punted across the rapids in a flat-bottomed boat and swirled in and out among the eddies of the famous bars. A Siwash family lived there by fishing with clumsy wicker baskets. Higher up could be seen some Chinamen, but whether they were fishing or washing we could not tell. Two transcontinental railroads skirted the canyon, one on each side, and the tents of a thousand construction workers stood where once were the camps of the gold-seekers banded together for protection. When we came back across the river an old, old man met us and sat talking to us on the bank. He had come to the Fraser in that first rush of '58. He had been one of the leaders against the murderous bands of Indians. Then, he had pushed on up the river to Cariboo, travelling, as he told us, by the Indian trails over 'Jacob's ladders'—wicker and pole swings to serve as bridges across chasms—wherever the 'float' or sign of mineral might lead him. Both on the Fraser and in Cariboo he had found his share of luck and ill luck; and he plainly regretted the passing of that golden age of danger and adventure. 'But,' he said, pointing his trembling old hands at the two railways, 'if we prospectors hadn't blazed the trail of the canyon, you wouldn't have your railroads here to-day. They only followed the trail we first cut and then built. We followed the "float" up and they followed us.'

What the trapper was to the fur trade, the prospector was to the mining era that ushered civilization into the wilds with a blare of dance-halls and wine and wassail and greed. Ragged, poor, roofless, grubstaked by 'pardner' or outfitter on a basis of half profit, the prospector stands as the eternal type of the trail-maker for finance.

[1] The same, of course, may be done to-day, with a like result, at many places along the Fraser and even on the Saskatchewan.

[2] This was the first Legislative Assembly to meet west of Upper Canada in what is now the Canadian Dominion. It consisted of seven members, as follows: J. D. Pemberton, James Yates, E. E. Langford, J. S. Helmcken, Thomas J. Skinner, John Muir, and J. F. Kennedy. Langford, however, retired almost immediately after the election and J. W. M'Kay was elected in his stead. The portraits of five of the members are preserved in the group which appears as the frontispiece to this volume. The photograph was probably taken at a later period; at any rate, two of the members, Muir and Kennedy, are missing.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.