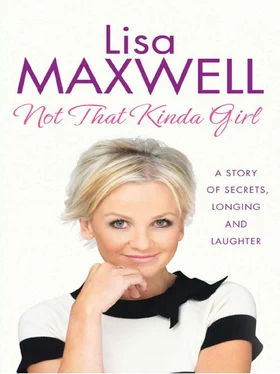

Lisa Maxwell

Not that Kinda Girl

A Story of Secrets, Longing and Laughter

For Paul and Beau

Title Page Lisa Maxwell Not that Kinda Girl A Story of Secrets, Longing and Laughter

Dedication

Introduction: Down at the Duke

1 Meet the Family

2 Early Days at the Elephant

3 Italia Conti Girls

4 My Secret Shame

5 First Love

Photographic Insert I

6 Moving On

7 Down to the Wire

8 The Lisa Maxwell Show

9 Life in LA

10 Meltdown

11 Coming Home

12 Falling in Love

13 Beautiful Beau

Photographic Insert II

14 Being DI Sam Nixon

15 Running on Empty

16 As One Door Opens …

17 Father Unknown

18 Finally Me

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Down at the Duke

As I walked towards the Duke of Sutherland in Walworth I could hear Nan’s voice belting out one of her favourite songs:

‘I’d like to be good …

And I know that I should …

I’m just not that kind of a girl …’

Just hearing her voice gave me a warm feeling. I’d always loved these words, because they’re funny and so familiar to me, from my earliest memories. As I pushed the heavy pub door open she was still at the piano, her left hand vamping a rhythm without moving across the keyboard, her right picking out the tune. She reached the last two lines:

‘Old Tommy Tucker …

Everyone knows he’s a dirty old … fella!’

The pub erupted in cheers and laughter, even though everyone there had heard the song before. I made my way through the fuggy, crowded bar, inhaling cigarette smoke and beer fumes, to the upholstered bench seat where Nan always sat with Grandad and their friends. She was basking in the applause and free drinks being sent across to their table.

‘Oh my Gawd, look who’s ’ere! Hide your wallet, Jim,’ she said when she spotted me.

‘I’m saying no, clear off out of here!’ Grandad would always say before I even had time to speak.

They were both laughing, and so were their friends.

I’d launch into my speech: ‘Guess what? I’ve seen these shoes in Grants in the Walworth Road, and they’ve only got one pair in my size. They were so nice, they said they’d put them by for me …’

As I wriggled myself in between them on the bench seat, I’d look at Nan.

‘You’d better speak to your grandad,’ she’d say, so I’d turn puppy-dog eyes on him.

‘Please, Grandad – they’re really nice,’ I’d tell him.

‘I bet they are,’ he’d say.

‘Please, Grandad, I won’t ask for anything else ever again!’

Huge guffaws from everyone round the table.

‘How much are they?’ he’d ask, already putting a hand in his pocket.

‘Only £14.99.’

‘Here’s fifteen nicker – clear off, that’s yer lot!’

I would skip out of the pub with the whole group smiling and watching me and, I imagine, thinking, ‘Aw, how could you resist her?’ Even though I was 16 I was tiny, slim and, because of my stage-school training, confident. I knew Nan and Grandad were proud of their little Lise whenever I went into the pub, they loved me – and I also knew, from an early age, that when Grandad had a few drinks inside him I could get anything out of him.

Nan, Grandad and Mum adored me. I lived with all three of them and I was the centre of their universes. I never went without anything; they spoiled me rotten. As far as Mum was concerned, nobody could ever point a finger at me and say I lacked anything. Except one big thing she was unable to give me: a father.

On my birth certificate there are two stark words, words branded on my soul: ‘Father Unknown’.

Today, with more than half of all babies born to unmarried couples according to the Office of National Statistics, the stigma of being illegitimate has pretty much gone. It’s a word you never hear now, and a good thing, too: it means illegal, beyond the law. That’s a terrible stamp to put on a child. I was born outside the law, and back then in the 1960s only 5 per cent of all babies did not have married parents.

My birth was something friends and family whispered about, hoping I wasn’t listening. A child born ‘out of wedlock’ was something to be ashamed of, the subject of gossip and innuendo: a stain on a family. This was something I was aware of from the very beginning. I always felt the love I was given was tainted with embarrassment and shame, a shame that has coloured my life in so many ways; it has affected my relationships, my work, everything. It’s a shadow that stretched long and deep and out of which I have only recently emerged into the sunshine.

Yes, I have always been bright and bubbly, funny, up for a laugh and a party, but the parties, the drinks and the laughter, everything was a way to keep on moving, to make sure I never stood still long enough to look deep inside myself. Finally, in the last few years, I have come off that merry-go-round and found a quiet, happy place in life where I can face up to myself and my story. I’ve come to terms with my birth; I know who I am. It’s been a long and at times difficult journey, but writing this book has also helped me find myself and lay to rest the ghosts that have haunted me.

CHAPTER 1

Meet the Family

I was only three years old, too small to see over the balcony outside our second-storey council flat at the Elephant and Castle, but there was a metal grille set into the brickwork that gave me a view of the estate below. While Nan tried to drag me back indoors, I was clinging to the bars, screaming and kicking hysterically. Below, I could see my mum getting into a minicab with a man in the back.

‘Your mother’s entitled to go out …’ Nan was saying as she struggled to contain my hysteria.

‘She’s with a man, she’s with a man!’ I was yelling.

‘Just get in the car, Val. She’ll be all right,’ Nan shouted to Mum as she finally prised me away and dragged me back inside.

Mum seemed to be in some sort of danger: the thought of her with a strange man was disturbing – I felt she couldn’t protect herself. And I hated her for leaving me to be with a man. This is my earliest memory. I can’t say exactly how I knew it was wrong; at that age you simply sense it from the way the grown-ups are trying to hide it. Mum didn’t say goodbye – she slipped out, secretively – and when I asked where she was, Nan and Grandad had exchanged sideways glances. So I panicked: I wanted her to come back. In some childish, unrealised way I wanted to save her from the terrible things about to happen to her.

Even then, too young to understand it properly, I had taken on board so much of the shame of being born out of wedlock and all the judgement that went with it that I felt my mum should be whiter than white and live like a nun. I had no idea how or why, but I knew a man had been involved in my arrival and this was something to be ashamed of, that it had been wrong. How did I develop such dark thoughts from such an early age, such fully formed moral opinions about her life? It was as though they seeped into me without anyone ever sitting me down and really spelling it all out. I don’t remember Nan and Grandad ever saying bad things about her, they were kinder than that, but the disapproval and half-heard gossip about my own mysterious ‘Father Unknown’ became part of me by osmosis.

I had picked up, probably from the whisperings of the grownups, that Mum had ruined her life by going with a man, and so I was terrified whenever I saw her with one. Men spelt trouble: disaster, shame, something dirty. So any attempt she had at a private life was thwarted, partly by the stigma of being an unmarried mother, but also – I’m ashamed to admit – by me, and from an early age I was determined to sabotage any chances she might have.

Читать дальше