When Johnny’s mother found out, she told him: ‘If you marry that girl, I want nothing more to do with you.’ It seemed he cared more for her than he did for Mum because he sent round a letter:

Dear Val, I won’t be there tonight. My mum and dad are going down to Cornwall and I’m going with them. I think it’s time we called it a day.

Mum left me with Grandad and rushed to where Johnny worked, but he’d already gone and she never saw him again. It was so cruel, and once again she was devastated. Every time she went out with a man she dreaded telling him she had a kid because she knew he wouldn’t want to see her again, she says. Although she didn’t tell me the story of my father until many years later when I had a family of my own, at the time she told me that no one wanted her because of me.

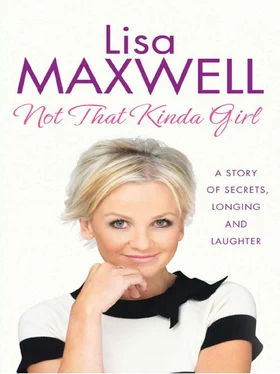

CHAPTER 2

Early Days at the Elephant

From the moment Nan and Grandad accepted me into their home, nothing was too good for me, no hand-me-downs. I had a big Silver Cross pram bought new for me from Morleys of Brixton. It was navy-blue and silver and Mum said she felt so proud of me when I was in it. She chose my name after Lisa Marie (the actress from Rock Around the Clock).

From day one, the way I looked was top of her list of priorities. She would do me up like a piece of installation art, all the best clothes, like a ‘Tiny Tears’ doll in my little white crochet bonnets and capes. She’d bump me down the stairs of Stephenson House and leave me on display for passers-by to admire. It was two floors down and she couldn’t see me from the balcony, but in those days no one worried about children being kidnapped. Perhaps there was a much greater sense of community – no one would do it today. Anyway, if anyone did want to snatch me they’d have to get past our old bulldog, Ricky, who was tied to the pram. Call it Elephant and Castle childcare.

Mum loved buying me clothes. When I was older she’d dress me up and take me over to the park, where she’d take pictures of me smelling flowers. She used to clean my patent shoes with milk to make them shine and spend ages on my hair, giving me doorknocker plaits with loops and always with ribbons. I remember when I was old enough for school she’d stand me on the side in the kitchen and make sure I looked immaculate while Noel Edmonds prattled away on Radio One.

As I grew older I identified with her need to create a good impression on the outside. I loved shopping for clothes, picking out my outfits for family dos. Whenever I got new clothes, I would ask Mum to hang them on the back of the bedroom door so I could fall asleep gazing at them. For Mum, dressing me up was a way to validate us both. ‘’Course we love ’er – look how nice she looks’ was the message she was sending out. It rubbed off on me and I’ve always worried about creating the right visual image, wanting people to like how I look; what started as a love of fashion became a way of controlling people’s perceptions of me. If I looked great on the outside, no one would search for the real stuff underneath. The last thing I ever wanted was for people to feel sorry for me – ‘Poor little Lise’ were not words I ever wanted to hear.

We were a lively family and there were lots of dos to dress up for. Nan and Grandad liked a good time and there were a few parties at number 15, spilling over from big family get-togethers in the pub. They used to put a board over the bath and put all the drinks in the bath. When I was a baby there was a scare because they thought someone had sat on me: it was one of my family’s favourite stories – even as a baby I was the butt of Nan’s humour. Apparently Alan’s friend Mickey lurched about drunkenly and had flopped down almost on top of me. When someone realised they couldn’t see me they thought I was squashed underneath him. They all thought it was hilarious.

Nan only ever expected one thing from me: if she was having a good time, I had to join in. ‘You’ve gorra have a laugh, int’yer?’ was her motto. She didn’t do misery. If anyone tried to burst her bubble, she’d say: ‘Fuck ’em if they can’t take a joke!’ And she’d encourage me to get up and dance in the middle of the boozed-up adults. ‘Gorn, babe,’ she’d say, and as the spirit of Chubby Checker entered my body I’d dance and shout.

‘Is it a bird?’

Boozed-up adults: ‘No!’

‘Is it a plane?’

‘No!’

‘Is it a twister?’

‘Yeah!’ and the whole of number 15 would be up on their feet, twisting the night away, with Little Lise right at the heart of it.

‘Aw, in’t she lovely?’ people would say. I knew I was everyone’s favourite.

As Nan’s granddaughter it was no surprise that I was a born entertainer, and she and Mum encouraged me. She enrolled me for dancing classes when I was about three and a half at the Renee Hayes Dancing School in a church hall just off the Walworth Road. I had a little red leotard and white tap shoes, through which my mum threaded red ribbons.

I was walking there one day with Mum when I was attacked by a dog off the lead: it was only little, like a Yorkshire terrier or something, but it bit my leg and locked its jaws onto me. Mum tried to kick it off, then picked me up and tried to swing it off. Eventually, when it was off me, I was taken to hospital for a tetanus jab which made me scream and put me off injections, so that put paid to my dancing for a while. I refused to go again but I still danced around at home. I remember once climbing on top of the sideboard, which had a drinks cabinet in it. This cabinet was made of shiny, fake walnut wood – I know it was plastic because we didn’t have any real wood in the house. Suddenly it fell over on top of me and there was smashed glass all around. I was badly cut and Mum had to rush me to hospital again; luckily this time I didn’t need an injection.

I wasn’t just spoilt with clothes, I was given every toy I ever wanted: if I wanted a walking, talking doll the same size as me, I got one. When I asked for a Swingy Doll, with beautiful white nylon hair she could swing to and fro, it was the same. And when I wanted a whole suite of Sindy bedroom furniture, it was there. I don’t remember being denied anything.

I must have been a cute kid when I was at nursery school because the teacher chose me as her bridesmaid when she got married. Mum was so proud: she and Nan took me down to Brighton for the wedding, and she was thrilled when people kept telling her what a pretty child I was. I was the centre of attention, just as I was throughout my childhood.

In some ways, I think Mum loved me too much. I was nearly suffocated by her love and fascination for me. I was top priority. I know that often happens to only children, but even as a child I found the responsibility of being put on a pedestal almost too great: it didn’t allow me to fail.

Nan and Grandad adored me in a more straightforward way, but even that caused problems. Their other kids had children, too, and Mum remembers a bit of resentment. Nothing was ever said openly to me about my father, but I heard things. At family gatherings people would say: ‘She’s a chip off the old block. She looks just like her dad.’ And ‘She favours her father, not her mother.’

From an early age there was clearly a short gene in my mix but Mum always tried to pass it off by saying it was to do with an infection after I was born. I’m the only one with a little button nose, too. When Mum introduced me for the first time people would often say, probably just out of politeness, I looked like her. She’d reply, ‘No, she’s not like me, but she’s the spitting image of her father.’ This was in my hearing, but not to me.

All I knew about him was his name – John Murphy – and I didn’t like it. It made me think I was half-Irish and I didn’t want to be a different nationality from everyone else in my family. The kids on the Rockingham Estate made fun of Irish people. Sometimes Mum would say, ‘You could have been a Murphy,’ and I hated it because I liked being a Maxwell.

Читать дальше