To understand these links, it is necessary to look more closely at the chemistry of the brain and some of the discoveries that have been made concerning how the brain and body ‘talk’ to each other. Depression has been found to be linked to changes in both the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis and the hypo – thalmus – pituitary – adrenal axis – two key hormonal circuits that link the brain and the body.

A major step towards understanding depression came with the discovery that the condition is linked to a shortage of the brain chemical serotonin, sometimes called the ‘happiness hormone’. This led to the development of a new class of antidepressants called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) which, as the name suggests, selectively block serotonin receptors to cause levels of serotonin – and feelings of wellbeing – to rise. These drugs, of which Prozac is the most well known, are now considered the standard treatment for depression.

Recently, researchers found that people who are depressed tend to have raised levels of thyroxine (T 4). At the same time, they have disturbances in their body clock causing lower daytime levels and a lower-than-normal night-time surge of thyroid-stimulating hormone, thought to be due to lack of serotonin. This is yet another example of how the brain and body communicate. Some doctors also suggest that the activity of T 3is also reduced, although this is not as yet supported by any clear evidence.

A number of psychiatrists, particularly in the US, have found that a T 3plus antidepressant ‘cocktail’ helps lift depression faster in the 30–40 per cent of people who seem to be resistant to antidepressants. Interestingly, adding the more usual thyroid treatment, T 4, has not proved effective, which suggests that the ability to convert T 4to T 3in the brain may be damaged in depressed people. Although most studies were carried out with the older tricyclic antidepressants that are not as widely used these days, it is thought that adding a dash of T 3to an SSRI might be equally effective.

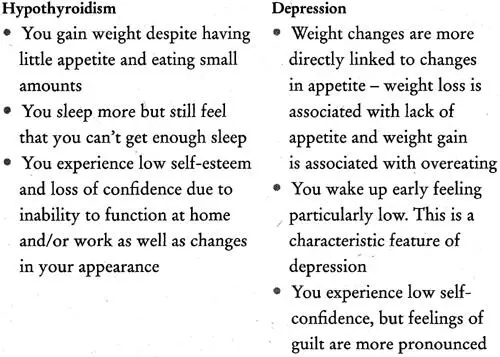

It may not always be easy for you – or your doctor – to distinguish between depression and hypothyroidism because the two conditions have many symptoms in common. In fact, some doctors surmise that an underfunctioning thyroid may be an indicator of depression. Others think that depression can put you more at risk of developing thyroid antibodies by impairing immune function, which may, in turn, lead to hypothyroidism.

Carol’s story is fairly typical:

I felt extremely fatigued, had trouble getting up in the morning and wanted to sleep all day. Sometimes I took a day or two off work and did just that – slept for 24 hours. I was also very tearful and had problems concentrating, making decisions, even thinking. I couldn’t watch TV or read – it was too much effort. I took about three months off work. I had a nice GP at the time and he diagnosed depression. I had a feeling it was something more physical as I didn’t feel depressed in the way it was described in the books. I wanted to do things, but I had no energy. I took antidepressants for five years. They helped my mood, which enabled me to return to work, but I had little energy for anything else.

Table 3.1 Symptoms common to both hypothyroidism and depression

| • Feeling miserable and ‘down in the dumps’ |

| • Anxiety |

| • Irritability |

| • Loss of interest or pleasure in things that you used to enjoy, such as sex |

| • Lack of energy |

| • Feeling tired all the time |

| • Weight changes |

| • Appetite changes |

| • Sleep disturbances |

| • Difficulty concentrating |

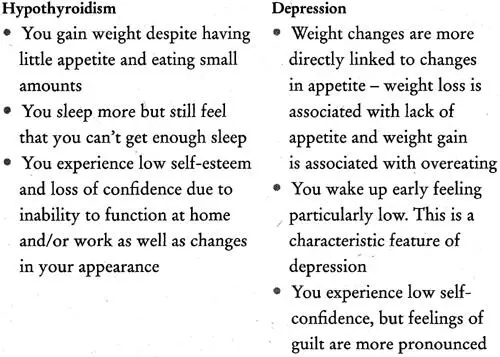

Table 3.2 Clues to help you to determine whether you have hypothyroidism or depression

Christine, whose underactive thyroid went undiagnosed for years, urges women not to be fobbed off with a diagnosis of depression if the symptoms don’t improve with antidepressant treatment. She was one of the few who developed myxoedema coma, a potentially life-threatening condition in which body temperature drops severely, brought on by untreated hypothyroidism. It can also cause low blood sugar and seizures, and lead to death. The coma can be triggered by cold, illness, infection or injury, and drugs that suppress the central nervous system. Although rare, it can still happen, as Christine recalls:

After years of to-ing and fro-ing to the doctor, I was referred to a psychiatric unit and diagnosed as chronically depressed. I was prescribed lithium [a drug used to treat manic-depression]. Within six months, I was comatose – my body grinding to a halt and my kidneys failing. I heard the doctors talking outside my room saying it should never have happened.

Although such an occurrence is extremely rare, it does underline the importance of persistence and of getting a proper diagnosis.

Why Does the Thyroid Become Underactive?

There are two main types of hypothyroidism: primary, when the thyroid is the source of problems; and secondary, when a fault in the hypothalamus or pituitary has a knock-on effect on the thyroid.

• Primary hypothyroidismcan be brought on by:

• thyroiditis (inflammation of the thyroid), a feature of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis ( see page 49 ) and postpartum thyroiditis (PPT)

• surgical or medical treatment for an overactive thyroid ( see Chapter 5 ) or surgery and/or radiotherapy for certain kinds of cancer

• prescription medications and over-the-counter drugs containing iodine (iodides), such as lithium for treating manic-depression, and some cough remedies

• congenital (inborn) problems affecting the thyroid, such as absence or abnormal development of the thyroid or errors of metabolism ( see Chapter 9 ).

• Secondary hypothyroidismis caused by failure of the hypothalamic – pituitary – thyroid hormonal axis leading to deficient secretion of hormones by the hypothalamus or pituitary, caused by:

• known damage to the hypothalamus or pituitary as a result of previous surgery, meningitis, trauma or radiation to the brain

• the development of tumours or cysts.

Although many of the symptoms of an underactive thyroid are common to both primary and secondary hypothyroidism, there are some suggestive differences that either you or your doctor may notice.

Table 3.3Clues to help you determine whether you have primary or secondary hypothyroidism

| Primary hypothyroidism |

Secondary hypothyroidism |

| Periods are likely to be heavier |

Periods may be absent (amenorrhoea) |

| Skin and hair are coarse |

Skin and hair are dry; skin may be pale and lacking in pigment |

| Breasts remain normal-sized |

Breasts may be small and shrunken |

| Heart is enlarged due to pericardial effusion (fluid accumulation in the sac surrounding the heart) |

Heart is small |

| Blood pressure and blood sugar levels are normal |

Blood pressure is low, often with low blood sugar (hypoglycaemia) due to adrenal insufficiency or a shortage of growth hormone |

Is Your Thyroid Underactive?

Symptoms of hypothyroidism are not always easy to detect. Table 3.4 lists some symptoms that you may experience, that others may notice or that your doctor may detect.

Читать дальше