Don’t believe those people who wax lyrical about the good old days of gobstoppers the size of your head, either. No, those Creme Eggs haven’t got smaller. Your hands have got bigger. In fact, with very few exceptions, the tuck shop fare of youth is served in heftier portions than ever before, as the waddling, wobbling outlines of twenty-first-century obesity crises serve to illustrate.

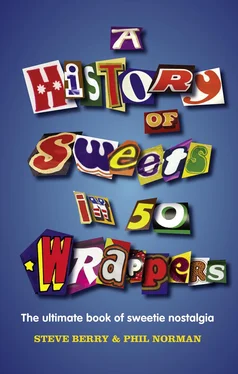

So here it is, then, your very own unnatural preservative of the best of the Great British sweet shop. Go ahead, dive in – but don’t spoil your tea, now.

Munchies (1957), Mackintosh’s crunchy answer to Rolo. Stablemates Mintola and Delight not pictured.

50 WRAPPERS

‘Unforgettabubble, that’s what you are. Unforgettabubble, milk chocolate bar.’ A line of old King Cole for Rowntree’s Aero (1935).

For all the Wonka-esque mystique affected by chocolate makers, most confectionery innovations amount to ‘let’s bung this on top of this, stick some chocolate on it’. The invention of the Aero, however, really did involve science. Rowntree’s technicians frothed up some liquid chocolate with a whisk, poured it into moulds and then – the clever bit – reduced the surrounding air pressure drastically so the tiny bubbles of froth swelled up to a decent size. Then it was a matter of passing the moulds through ice-cold water to set, covering the result with a layer of solid chocolate, and the job was done.

It caused a sensation when it came out, albeit one helpfully whipped up by Rowntree themselves. The exciting new texture, they claimed, ‘stimulates the enzyme glands’ – a bit of shameless quackery they were soon forced to take back. Initially great sales began to tail off, in part due to an assortment of rivals appearing on the scene with undue haste, in particular Fry’s two tryouts, the Ripple and the All-Chocolate Crunchie. Add to that a disputed patent, and things got panicky at Rowntree headquarters. Fruit and nut and whole nut variants were hurriedly bunged out to support the ailing novelty. Sales levelled off after a while, and the Aero, while no longer a craze, remained steady-as-she-goes.

They couldn’t resist mucking about, though. An Aero Wafer introduced in 1950 didn’t hang about too long, but in ’59 the bright idea of changing the aerated centre from chocolate to peppermint gave the bar a new lease of life, and with orange and coffee centres arriving over the next couple of years, a nice little family was built up that would tick over happily for decades, with just a new campaign based around the word ‘bubbles’ knocked out every few years. Oh, and a short-lived lime variant in 1971.

Then, cometh the ‘80s, cometh the Cadbury’s Wispa. Big trouble in Rowntreeland as the potential Aero spoiler was worriedly picked over. Luckily the two-year gestation period Cadbury took to get the Wispa going nationwide allowed Rowntree to remake the Aero in its image. By September of 1982, gone was the six-segmented flat format, a bumpy chocolate version of the traffic-calming measures in a well-to-do Cotswold village. In came the handy ingot size. In the process, something – no one was quite sure what – changed. The chocolate had become softer. No, the bubbles were bigger. No, it’s the taste... It scarcely mattered, as the new bar more than held its own against the Bournville parvenu. But even today, plenty of former stalwart Aerovians feel slighted by the changes, their enzyme glands no longer stimulated in quite the same way.

A sign of civilisation. Aztec (1967), swiftly sacrificed to the gods of chocolate nostalgia.

This is a tale of two cultural cornerstones. On the one hand, the mighty Quetzalcoatl, feathered serpent god of the ancient Aztecs, who gave his people the sacred gift of chocolate via a beam of heavenly light, bringing them universal wisdom and Type 2 diabetes. (Sadly, the one bit of knowledge that might have been some use, namely ‘If you see these Spanish blokes with big shiny helmets, run like the clappers,’ slipped the feathered one’s mind.) In the blue corner, there’s the equally legendary rival to the Mars bar, opportunistically cooked up by Cadbury in a lean period and promoted with a travelogue-swish TV campaign filmed at one of your actual Mexican temples, only to vanish mysteriously four years later. The former lived on for centuries in folk memory and overpriced Acapulco gift shops. The latter enjoyed a similarly fertile afterlife, becoming the de facto nostalgic touchstone for the first wave of alternative comedians (Ben Elton’s swing-top bin was so long unemptied it had ‘Aztec wrappers in the bottom’).

It’s perhaps fair to say that Elton’s championing of fair-trade didn’t tally too well with the Aztec’s imperialistic undertones, a state of affairs not helped by the life-size cardboard warrior chieftains installed in newsagents the nation over, to the innocent delight of kids who’d gleefully perform a culturally inaccurate whooping war dance around them. All this happened, of course, while the Milky Bar kid was doing his bit for the Native North Americans. To complete the continental clean sweep, the 1980s, when you’d have thought people would have calmed down a bit, saw the launch of the otherwise unremarkable Rowntree’s Inca. We could, of course, all be very smart and ironic about such things by the time the Aztec made the slightest of slight returns in the year 2000.

Instigating a Mexican crave. Safety-pin propaganda on behalf of Cadbury.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.