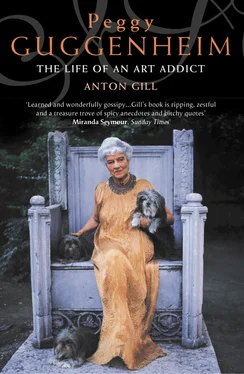

Peggy’s allusions to fiancés and boyfriends and romantic – though still platonic – attachments are frequent and insistent enough to make one suspect that she was either protesting too much or trying to prove to herself that she was genuinely attractive to the opposite sex. If that were the case, the cause is not far to seek. All three sisters had been very pretty children, but while Benita and Hazel grew into beautiful women, Benita with a placid temperament, Hazel with an unruly and scatterbrained one, Peggy lost the early delicacy of her looks. With her lively eyes and a personality to match, her long, slim arms and legs, and her too-delicate ankles, her attractiveness was not in doubt; but she had one very serious flaw: she had inherited the Guggenheim potato nose. Now she decided to have something done about it.

Plastic surgery wasn’t perfected until the Second World War, was in its infancy early in 1920, when Peggy went to a surgeon in Cincinnati who specialised in improving people’s appearances. She had set her heart on a nose that would be ‘tip-tilted like a flower’, an idea she’d got partly from her younger sister’s pretty nose and partly from reading Tennyson’s Idylls of the King :

Lightly was her slender noseTip-tilted like the petal of a flower.

Unfortunately the surgeon, though he was able to offer her a choice of noses from a selection of plaster models, wasn’t up to the job. After working on his patient for some time he stopped. Peggy was only under local anaesthetic, which wasn’t enough to prevent her from suffering great pain, so when the surgeon told her he was unable to give her the nose she’d chosen after all, she told him to stop, patch up what he’d done, and leave things as they were.

According to Peggy, the result was worse than the original, but to judge by the photographs taken of her in Paris by Man Ray only four years later, the nose is not as offensive as she makes it sound, though in the years which followed it coarsened, and she was careful to avoid being photographed in profile. She made light of the whole experience, which was brave of her, given that she also tells us that her new nose behaved like a barometer, swelling up and glowing at the approach of bad weather. It is hard to judge from ‘before’ and ‘after’ pictures whether the surgeon actually altered her nose all that much. Its shape was inherited by her son Sindbad. One person who knew her well in later life wonders if the whole story of the nose job wasn’t an invention, but this seems unlikely. Peggy was obsessed with the shape of her nose, and with the idea that because of it she was ugly. It has been said that she was still thinking of having a fresh operation late in life, though her nose never impeded her sex life (something which was extremely important to her); and by the 1950s, when cosmetic surgery was much safer and more predictable, she had moved on emotionally and psychologically from serious concern about such things.

People were cruel about Peggy’s nose throughout her life. In the thirties Nigel Henderson, the son of her friend Wyn, said that she reminded him of W.C. Fields, and the same resemblance was called to mind by Gore Vidal decades later. The painter Theodoros Stamos said, ‘She didn’t have a nose – she had an eggplant,’ and the artist Charles Seliger, full of sympathy and regard for Peggy, remembered that when he met her in the 1940s her nose was red, sore-looking and sunburnt: ‘You could hardly imagine anyone wanting to go to bed with her, to put it cruelly.’ Peggy’s heavy drinking during the 1920s, thirties and early forties didn’t help. And however much she made light of what she regarded as an impediment, there is no doubt that the shape of her nose reinforced her low self-esteem.

Notwithstanding his failure, the surgeon relieved her of about $1000 for the operation. Bored and in need of consolation, Peggy took a friend to French Lick, Indiana, and proceeded to gamble away another $1000 before returning to New York, still with little or no idea of what to do with herself, though some of the seeds Lucile Kohn had planted were showing signs of sprouting. Margaret C. Anderson, founder-editor of the then six-year-old Little Review , perhaps prompted by Kohn, approached her for money and an introduction to one of her moneyed uncles. Peggy didn’t help with cash, but sent Anderson off to Jefferson Seligman, in the hope that even if she didn’t get the $500 she sought, she might at least get a coat out of the uncle.

The Little Review was one of the most important and long-lived of the literary and arts magazines that flourished in the first half of the twentieth century, before most of them were superseded by television. It moved home in the course of its fifteen-year life from Chicago to San Francisco, thence to New York, and finally to Paris, publishing many of the great names of contemporary literature, including T.S. Eliot, W.B. Yeats, William Carlos Williams, Ford Madox Ford and Amy Lowell. Ezra Pound was its foreign editor from 1917 to 1919, and its major claim to fame was its serialisation, beginning in 1918, of James Joyce’s Ulysses. It may seem odd that Peggy was not keener to associate herself with a review which was concerned with so many of the people and ideas she was soon to embrace; but it wasn’t long before she became involved, albeit tangentially, with the literary world.

Needing above all to work, and to meet people outside her immediate social circle, Peggy took a job with her own dentist as a temporary nurse-cum-receptionist, filling in for the regular girl who was off sick. The work came to an end when the proper nurse returned, much to Florette’s relief; she hadn’t liked the idea of her friends and acquaintances discovering that one of her daughters was working as a dental nurse. Florette’s relief was, however, short-lived. Peggy now took a much more significant, though unpaid, job, as a clerk in an avant-garde bookshop, the Sunwise Turn, not far from home, in the Yale Club Building on 44th Street. The bookshop was run by Madge Jenison and Mary Mowbray Clarke. Clarke was the dominant partner, and ran the store as a kind of club. She only sold books she believed in, and literati and artists were constantly dropping in and staying to talk. Peggy quickly found that here was a society to which she wanted to belong.

She’d got the job through her cousin Harold Loeb, seven years her senior, who had injected $5000 into the Sunwise Turn when it ran into financial difficulties, and was now a partner in the enterprise. Harold was the son of Peggy’s aunt Rose Guggenheim and her first husband, Albert Loeb, whose brother James was the founder of the Loeb Classical Library.

Harold inherited a strong literary inclination. He joined the great exodus of young Americans to Europe in the early 1920s, published three novels and an autobiography, and founded and ran, first from Rome and then from Berlin, a short-lived but immensely important arts and literature magazine called Broom , which published, inter alia , the works of Sherwood Anderson, Malcolm Cowley, Hart Crane, John Dos Passos and Gertrude Stein. Aimed at an American readership, Broom also ran reproductions of works by such artists as Grosz, Kandinsky, Klee, Matisse and Picasso, all then little-known in the New World, and many of whom were still struggling for recognition in the Old. It was always a struggle to keep Broom afloat, and at the outset Harold appealed to his uncle Simon for funds. This may not have been tactful. Harold belonged to another ‘poor’ Guggenheim branch – his mother had been left only $500,000 by her father. Uncle Simon had given him a well-paid job with the family concern as soon as he graduated from Princeton, but a life in business had not suited Harold at all and he had left to become, to all intents and purposes, a bohemian. His request was frostily rejected: ‘I have since discussed with all your uncles the question of the endowment you wished for Broom , and I am reluctantly obliged to inform you we decided we would not care to make you any advances whatsoever. Our feeling is that Broom is essentially a magazine for a rich man with a hobby … I am sorry that you are not in an enterprise that would show a profit at an earlier date.’

Читать дальше