In one more year Peggy would reach her majority. Then she could really spread her wings.

CHAPTER 5 Harold and Lucile

Although there wasn’t a general penchant for marrying well-placed Englishmen among the Guggenheim girls, several did manage it. There was a pronounced anglophilia in some branches of the family. Uncle Solomon adored Great Britain. He went grouse-shooting in Scotland and set up his aristocratic elder son-in-law as a beef farmer in Sussex by giving his daughter Eleanor what she later described as a ‘useful little cheque’. Eleanor married Arthur Stuart, the Earl Castle Stewart (the family seat was in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland, until it was blown up by the IRA in 1973), and lived most of her life in England, a pillar of the Women’s Institute and a great contrast to her cousin Peggy, though one of her sons recalls that she had even less time for Hazel. Solomon’s daughter Barbara married Robert J. Lawson-Johnston, who, though brought up as an American citizen, had been born in Edinburgh (he was the son of the founder of the company that makes Bovril) and educated at Eton. Their son Peter was later raised to the captaincy of the Solomon Guggenheim concerns by his mother’s cousin Harry.

Uncle Solomon’s third daughter, Gertrude, also lived in England, in a house specially built for her by her father – Windyridge in Sussex, where Eleanor’s son Simon now lives – though few concessions were made for her in its design. Gertrude was disabled and well below average height. She gave her life to good works; during the Second World War she took in evacuees, and she habitually made it possible for underprivileged children from London’s East End to take summer holidays with her in the country. ‘She used to take them through the millpond to get the lice off them,’ her nephew Patrick, Earl Castle Stewart, remembers.

This love of Britain and Ireland was partly motivated by a desire to disguise Jewish mainland European peasant antecedents, and went along with the desire to assimilate, to cease to be the target of anti-Semitism, against which no amount of wealth was proof. Within the society in which Peggy grew up, the marriage one made was crucial. It’s probable that Florette and Ben, though less conventional than Ben’s brothers, wished for similar marriages to those their cousins had made, for their three daughters. And Peggy and Hazel did grow up to feel a great affection for England.

But marriage was the last thing on Peggy’s mind in 1918, and already she was showing signs of having no intention of following her mother and older sister into the social round of the New York Jewish upper crust. One influence in particular must have made Florette shudder, yet it was one which profoundly shaped Peggy’s thinking, though she was never overtly political, at least until her middle years. Religious belief never played any role in her life whatsoever.

After her couple of years at the Jacoby School were over, Peggy was at a loose end. Her active mind had been stimulated in a way which could never now be satisfied by the narrow bounds of the society into which she had been born, and she took private courses in economics, history and Italian. Through them she met a teacher called Lucile Kohn.

Kohn was Peggy’s first mentor. In her mid-thirties by 1918, she had initially been a supporter of the Democratic President Woodrow Wilson, but, becoming disaffected with him during his second term of office, she had embraced the Socialist cause. Kohn may have seen a disciple in the rebellious teenager before her, a poor little rich girl from a conservative background; but if she did, she sought to persuade by example rather than by proselytisation. Kohn was a pragmatic Socialist, believing that Socialism was the only way to improve the lot of humankind. Peggy was not an immediate convert, but Lucile planted seeds in her mind which would grow and bear fruit in the future, though not in the way the teacher imagined. Later on, when Peggy had come into her inheritance and moved to Europe, she sent Kohn ‘countless $100s’. Kohn was the first of many individuals whose talent Peggy thought worth supporting for a greater or lesser period of their lives, and Peggy’s subsidy changed Kohn’s life more than Kohn’s influence changed hers, for it enabled her to devote herself to her chosen cause full-time. ‘As I look back over my long life (ninety years) I list the few people who made a tremendous change in my life,’ Kohn wrote to Peggy in 1973, ‘– a change for the better – and Peggy Guggenheim is one of the four.’ She told Virginia Dortch, ‘I really think we learned and felt together that people like the Guggenheims had an obligation to improve the world.’ This was an obligation to which the Guggenheims responded through a number of foundations and trusts set up when the various family fortunes had been made.

Peggy was politically influenced by Kohn, but still she didn’t know what to do with herself. Together with a desire for education had come a desire to work, to occupy her life positively. She had had a run of boyfriends – whom, as we’ve seen, she called ‘fiancés’ – during the war, but she was dismissive of them. Benita’s marriage in 1919 to an American airman, Edward Mayer, who had just returned from Italy – a marriage of which Florette disapproved because Mayer did not come from the right background and had only a modest fortune – only affected Peggy in the sense that she felt abandoned by her sister. She disliked Mayer, and is profoundly unkind about him in her autobiography, though she was a witness at the City Hall wedding, together with a lifelong friend, also called Peggy (who would later marry Hazel’s second husband after his divorce and one of the most traumatic episodes in the entire Guggenheim family story). Benita and Edward, who seems to have been, if anything, rather strait-laced, had a successful marriage, marred only by Benita’s inability to have children. The marriage ended only with Benita’s untimely death in 1927, following another unsuccessful pregnancy. Edward was even blamed for this, since it was felt that Benita should not have been permitted to try again for a child.

An outlet for Peggy’s energies still didn’t suggest itself, and in the summer of 1919, passing her twenty-first birthday, she came into the money she was due to inherit from her father. The timing was good, for it was seven years since Ben’s death, and it had taken her Guggenheim uncles exactly that long to sort out his affairs. Half of the inheritance had to be maintained as capital in trust. The uncles sensibly suggested that the entire amount be absorbed into the Trust Fund, and Peggy just as sensibly agreed, with the result that her capital yielded an income of about $22,500 a year – not bad in those days, even for a ‘poor’ Guggenheim.

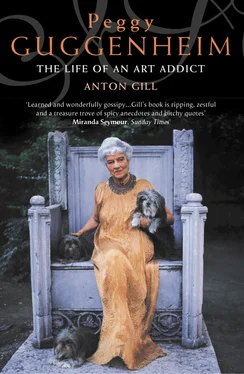

Hitherto in 1919, apart from Benita’s wedding, the only major excitement had been winning first prize at the Westchester Kennel Club dog show with the family Pekinese, Twinkle – one of the first of many small dogs that Peggy would keep throughout her life. Now, things could really take off. Above all, she was legally independent, and could free herself of her mother’s influence – much to Florette’s distress.

Peggy decided to embark on a grand tour of North America, taking as her companion a female cousin of Edward Mayer. They travelled to Niagara Falls, and thence to Chicago and on to Yellowstone National Park. After that they spent time in California, visiting the nascent Hollywood, which didn’t impress her: she dismissed the film industry people she met as ‘quite mad’. Then they dipped into Mexico, before travelling north along the west coast all the way to Canada. From there they returned to Chicago, where they rendezvoused with a demobbed airman, Harold Wessel, whom Peggy described as her fiancé. He introduced her to his family, whom she proceeded, perhaps deliberately, to insult, telling them with typical forthrightness that she found Chicago, and them, very provincial. As she prepared to leave on the train to New York, Wessel broke off the engagement, which didn’t cause Peggy distress. She probably only became engaged to him to copy Benita, and was relieved to get out of it.

Читать дальше