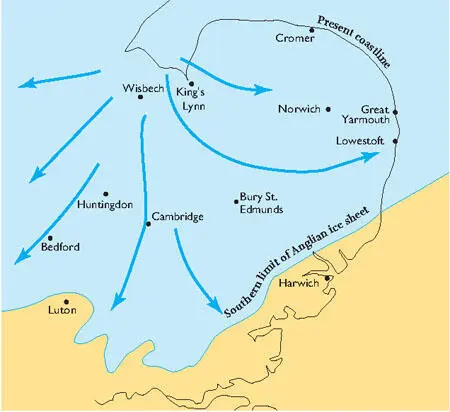

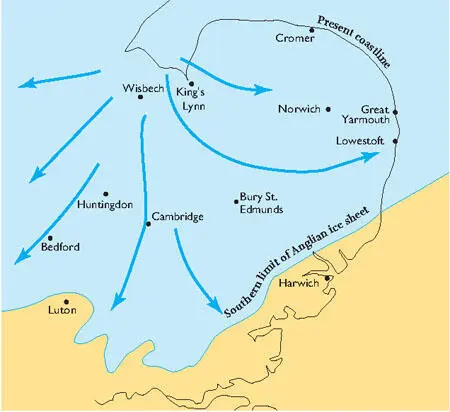

FIG 14.The Anglian ice sheet.

Much of the rest of the surface blanket that accumulated during the last 2 million years was deposited by the rivers that were draining the land or any ice sheets present. As ice sheets have advanced and retreated, so have the rivers changed in their size and in their capacity to carry debris and erode the landscape. Rivers have therefore been much larger in the past as melting winter snow and ice produced torrents of meltwater, laden with sediment, which scoured valleys or dumped large amounts of sediment. The gravel pits scattered along the river valleys and river terraces of Southern England, from which material is removed for building and engineering, are remnants of the beds of old fast-flowing rivers which carried gravel during the cold times.

There are no ice sheets present in the landscape of Figure 16. The scene is typical of most of the Ice Age history (the last 2 million years) of Southern England, in that the ice sheets lie further north. It is summer, snow and ice are lingering, and reindeer, wolves and woolly mammoths are roaming the swampy ground. The river is full of sand and gravel banks, dumped by the violent floods caused by springtime snow-melt. The ground shows ridges of gravel pushed up by freeze-thaw activity, an important process in scenery terms that we discuss below.

FIG 15.Boulder clay or till, West Runton, north Norfolk.

The present-day Arctic has much to tell us about conditions and processes in Southern England during the cold episodes of the Ice Age. Much of the present-day Arctic is ice-sheet-free, but is often characterised by permanently frozen ground ( permafrost ). When the ground becomes frozen all the cracks and spaces in the surface-blanket materials and uppermost bedrock become filled by ice, so that normal surface drainage cannot occur. In the summer, ice in the very uppermost material may melt and the landscape surface is likely to be wet and swampy. Ice expands on freezing, and so the continuous change between freezing and thawing conditions, both daily and seasonally, can cause the expansion of cracks and the movement of material, with corresponding movements in the surface of these landscapes. This movement can cause many problems in the present-day Arctic by disturbing the foundations of buildings and other structures.

FIG 16.Artist’s impression of Southern England, south of the ice sheet, during the Ice Age. (Copyright Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service & Nick Arber)

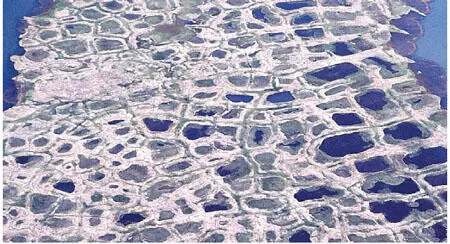

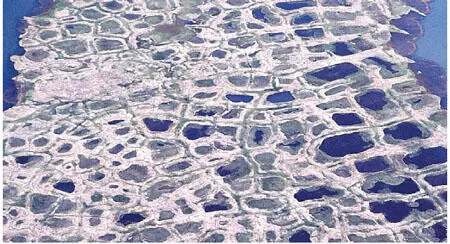

Remarkable polygonal patterns, ranging from centimetres to tens of metres across, are distinctive features of flat Arctic landscapes, resulting from volume changes in the surface blanket on freezing and thawing (Fig. 17). In cross-section the polygon cracks and ridges correspond to downward-narrowing wedges (often visible also in the walls of gravel pits in Southern England). Thaw lakes are also a feature of flat areas under conditions of Arctic frozen ground (Fig. 18). They appear to be linked to the formation of the polygonal features, but can amalgamate to become kilometres across and may periodically discharge their muddy soup of disturbed sediments down even very gentle slopes.

Not only can these frozen ground processes be studied in Arctic areas today, but they have left characteristic traces in many of the landscapes of Southern England. Some examples from Norfolk are illustrated in Chapter 8 (Figs 306 and 307), and these provide specific examples of the result of ancient freeze-thaw processes on a small scale. However, the more we examine the wider features of present-day landscapes across Southern England, the more it becomes clear that most have been considerably modified by the general operation of frozen ground processes during the last 2 million years. These processes are likely to have been responsible for the retreat of significant slopes and even for the lowering of surfaces that have almost no perceptible slope.

FIG 17.Polygonal frozen ground patterns on the Arctic coastal plain near Barrow, Alaska. (Copyright Landform Slides – Ken Gardner)

FIG 18.Thaw lakes, the larger ones several kilometres long, on the Arctic coastal plain near Barrow, Alaska. (Copyright Landform Slides – Ken Gardner)

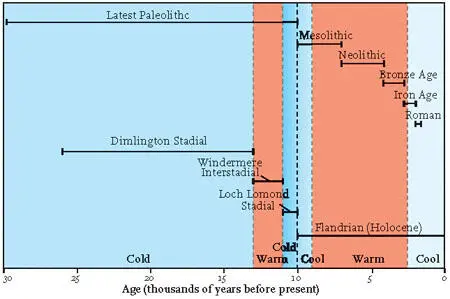

THE LAST 30,000 YEARS TIMESCALE AND RECENT MODIFICATION

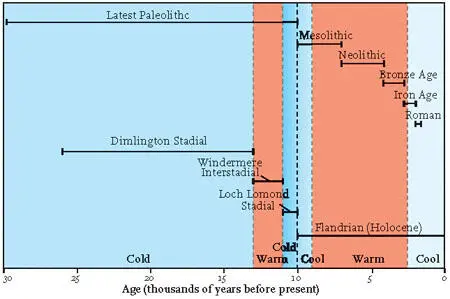

The timescale shown in Figure 19 covers a period during which various episodes have changed the landscapes of Southern England, creating our present-day world. These episodes include the dramatic rise in sea level and landward movement of the coastline caused by the warming of the climate following the last cold episode of the Ice Age. They also include the progressive changing of the countryside by people, leading up to the domination of some landscapes by man-made features.

FIG 19.Time divisions for the last 30,000 years (Late Pleistocene to Holocene).

| Time Division |

Years Before Present |

| Windermere Interstadial |

13,000–11,000 |

| Loch Lomond Stadial |

11,000–10,000 |

| Flandrian (Holocene) |

10,000-present |

| Mesolithic |

11,000–7,000 |

| Neolithic |

7,000–4,150 |

| Bronze Age |

4,150–2,750 |

| Iron Age |

2,750–1,950 |

| Roman |

1,950–1,600 |

The last 30,000 years have been warm, on average, relative to the previous 2 million years of the Ice Age. However, the higher level of detail available in this timescale makes it clear that climate change has not been one of uniform warming during this period. Short periods of colder climate, temporarily involving ice-sheet growth in the north of Britain (sometimes called stadials ) have alternated with short periods of warmer climate (referred to as interstadials ).

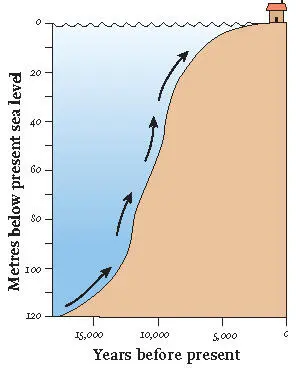

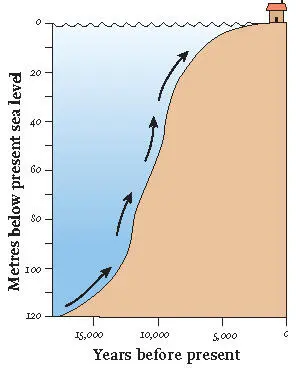

The coastline is the most recently created part of the landscape, and the most changeable. This is due, in large part, to the rise in sea level over the last 20,000 years, since the last main cold episode of the Ice Age (the Devensian). Twenty thousand years ago sea level was 120 m lower than it is today because of the great volumes of water that were locked away on land in the world’s ice sheets (Fig. 20). Land extended tens or hundreds of kilometres beyond the present-day coastline, and Southern England was linked to northern France by a large area of land (Fig. 21). Global climate started to warm about 18,000 years ago (Fig. 13) and the world’s ice started to melt, raising global sea level. The North Sea and the Channel gradually flooded, and Britain became an island between 10,500 and 10,000 years ago. This flooding by the sea is known as the Flandrian transgression and was a worldwide episode.

FIG 20.Graph of sea-level rise over the last 18,000 years.

Читать дальше