Knowledge of the processes causing the movement of large areas of the Earth’s surface (10–1000 km length scale) has been revolutionised by scientific advances made over the last 50 years. During this time, scientists have become convinced that the whole of the Earth’s surface consists of an outer shell of interlocking tectonic plates ( Fig. 12). The word tectonic refers to processes that have built features of the Earth’s crust (Greek: tekt, a builder). The worldwide plate pattern is confusingly irregular – particularly when seen on a flat map – and it is easier to visualise the plates in terms of an interlocking arrangement of panels on the Earth’s spherical surface, broadly like the panels forming the skin of a traditional leather football.

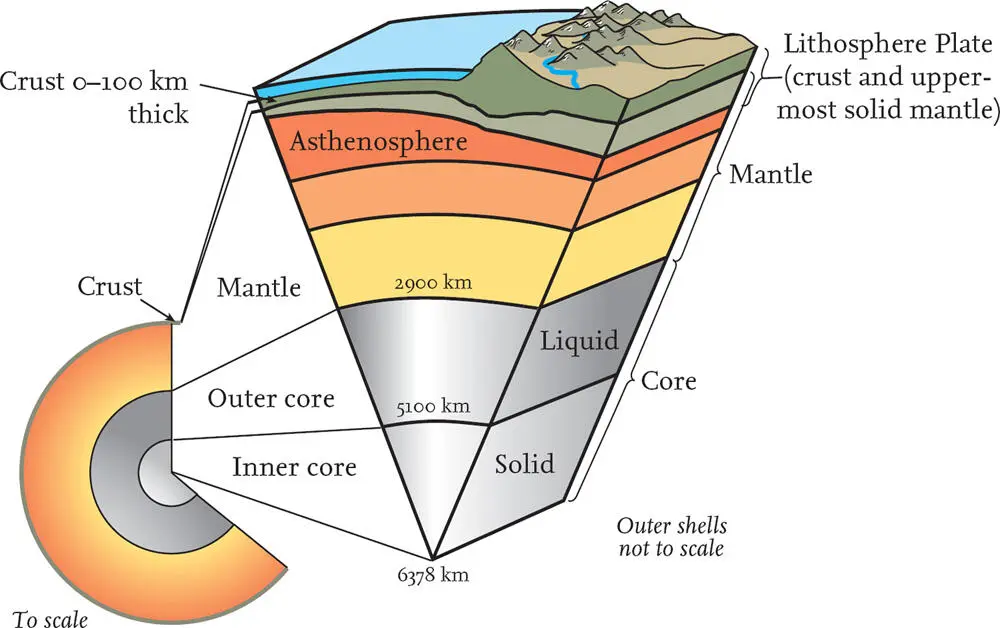

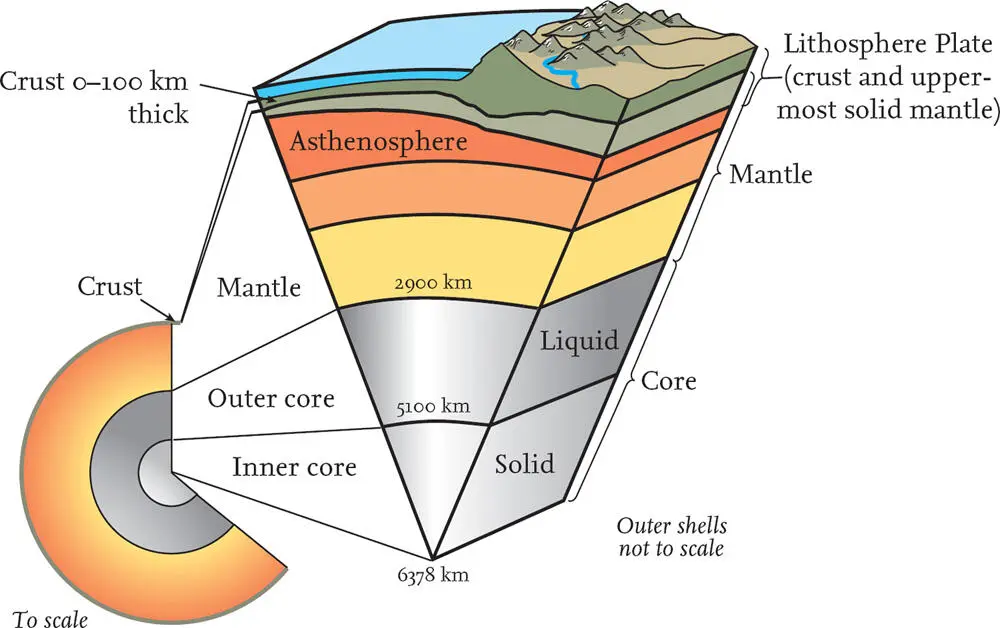

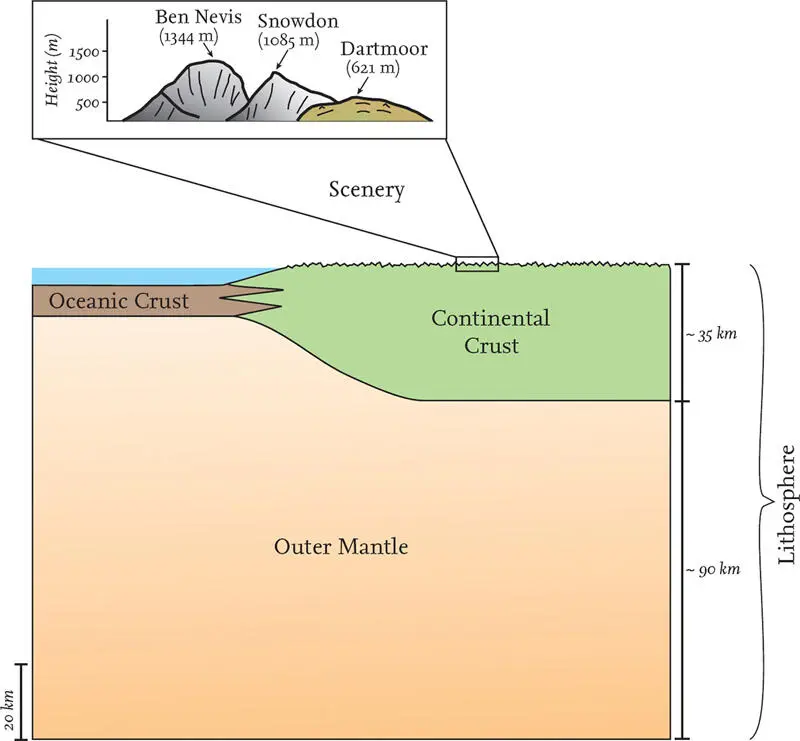

Tectonic plates are features of the lithosphere, the name given to the ~125 km- thick outer shell of the Earth, distinguished from the material below by the strength of its materials (Greek: lithos, stone). The strength depends upon the composition of the material and also upon its temperature and pressure, both of which tend to increase with depth below the Earth’s surface. In contrast to the mechanically strong lithosphere, the underlying material is weaker and known as the asthenosphere (Greek: asthenos, no-strength). Note that in Figure 13the crustal and outer mantle layers are shown with exaggerated thickness, so that they are visible.

FIG 12. World map showing the present pattern of the largest lithosphere plates.

FIG 13. Diagram of the internal structure of the Earth.

Much of the strength difference between the lithosphere and the asthenosphere depends on the temperature difference between them. The lithosphere plates are cooler than the underlying material, so they behave in a more rigid way when forces are generated within the Earth. The asthenosphere is hotter and behaves in a more plastic way, capable of deforming without fracturing and, to some extent, of ‘flowing’. Because of this difference in mechanical properties and the complex internal forces present, the lithosphere plates can move relative to the material below. To visualise the motion of the plates, we can use the idea of lithospheric plates floating on top of the asthenosphere.

The pattern of earthquake activity and actively unstable mountain belts corresponds very well with the pattern of the tectonic plates now recognised. The largest plates ( Fig. 12) clearly mark relatively rigid and stable areas of the lithosphere, with interiors that do not experience as much disturbance as their edges. Plates move relative to each other along plate boundaries, in various ways that will be described below. The plate patterns have been located by investigating distinctive markers within the plates and at their edges, allowing the relative rates of movement between neighbouring plates to be calculated. These rates are very slow, rarely exceeding a few centimetres per year, but over the millions of years of geological time they can account for thousands of kilometres of relative movement.

It has proved much easier to measure plate movements than to work out what has been causing them. However, the general belief today is that the plates move in response to a number of different forces. Circulation (convection) within the mantle is driven by temperature and density differences, but other forces are also at play. Where plates diverge, warm material rises from within the Earth to fill the surface gap, and, being warmer, it may also be elevated above the rest of the plate, providing a pushing force to move the plate across the surface of the Earth. At convergent boundaries, cold, older material sinks into the asthenosphere, providing a pulling force that drags the rest of the plate along behind it. Deep within the Earth, the sinking material melts and is ultimately recycled and brought back to the surface to continue the process.

Knowledge of how tectonic plates interact provides the key to understanding the movement history of the Earth’s crust. However, most people are much more familiar with the geographical patterns of land and sea, which do not coincide with the distribution of tectonic plates ( Fig. 12). From the point of view of landscapes and scenery, coastlines are always going to be key features because they define the limits of the land; we make no attempt in this book to consider submarine scenery in detail.

The upper part of the lithosphere is called the crust ( Fig. 13). Whereas the distinction between the lithosphere and the asthenosphere is based upon mechanical properties related to temperature and pressure, the distinction between the crust and the lower part of the lithosphere is based upon composition. Broadly speaking, there are two types of crust that can form the upper part of the lithosphere: continental and oceanic. An individual tectonic plate may include just one or both kinds of crust.

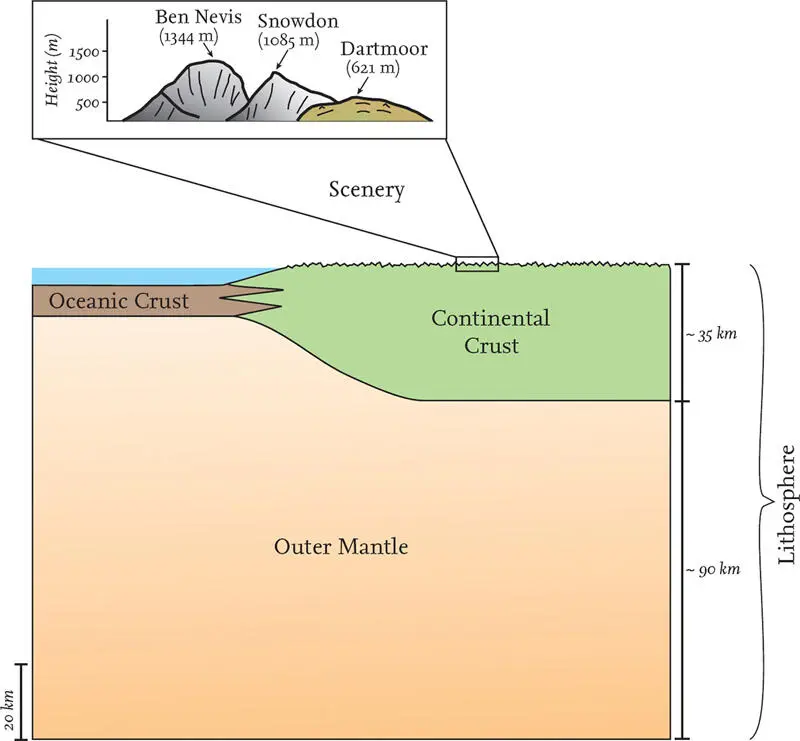

Continental crust underlies land areas and also many of the areas covered by shallow seas. Geophysical work shows that this crust is typically about 30 km thick, but may be 80–90 km thick below some high plateaus and mountain ranges. The highest mountains in Britain are barely noticeable on a scale diagram comparing crustal thicknesses ( Fig. 14). Continental crust is made of rather less dense materials than the oceanic crust, or the mantle, and this lightness is the reason why land surfaces and shallow sea floors are elevated compared to the deep oceans. Much of the continental crust is very old (up to 3–4 billion years), having formed early in the Earth’s life when lighter material separated from denser materials within the Earth and rose to the surface.

Oceanic crust forms the floors of the deep oceans, typically 4 or 5 km below sea level. It is generally 5–10 km thick and is distinctly more dense than continental crust. Oceanic crust only forms land where volcanic material has been supplied to it in great quantity (as in the case of Iceland), or where other important local forces in the crust have caused it to rise (as is the case in parts of Cyprus). Oceanic crust is generally relatively young (only 0–200 million years old), because its greater density and lower elevation ensures that it is generally subducted and destroyed at plate boundaries that are convergent.

FIG 14. Scale diagram comparing average thicknesses of oceanic and continental crust and lithosphere.

Figure 12shows the major pattern of tectonic plates on the Earth today. The Mercator projection of this map distorts shapes, particularly in polar regions, but we can see that there are seven very large plates, identified by the main areas located on their surfaces. The Pacific plate lacks continental crust entirely, whereas the other six main plates each contain a large continent (Eurasia, North America, Australia, South America, Africa and Antarctica) as well as oceanic crust. There are a number of other middle-sized plates (e.g. Arabia and India) and large numbers of micro-plates, not shown on the world map.

Figures 12and 15also identify the different types of plate boundary, which are distinguished according to the relative motion between the two plates. Convergent plate boundaries involve movement of the plates from each side towards the suture (or central zone) of the boundary. Because the plates are moving towards each other, they become squashed together in the boundary zone. Sometimes one plate moves below the other in a process called subduction, which often results in a deep ocean trench and a zone of mountains and/or volcanoes, as well as earthquake activity ( Fig. 15). The earthquakes that happened off Indonesia in December 2004 and off Japan in March 2011 were two of the strongest known since records began. Both seized world attention because of the horrifying loss of life cause by the tsunami waves they generated. Both were the result of sudden lithosphere movements of several metres on faults in the convergent subduction zones where the Australian and Pacific plates have been moving under the Eurasian plate ( Fig. 12).

Читать дальше