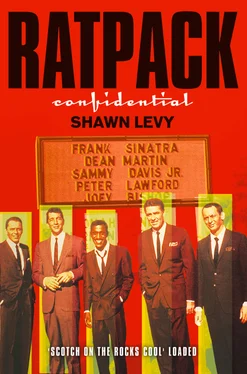

As in the movies, he seemed to have earned the right to his station; what’s more, as a singer, he expanded the very art form. He cut whole albums of songs built on the same musical ideas—saloon songs, swing numbers, waltzes—and even lyrical ideas: flying, dancing, the moon. Through the decade, he made the greatest pop records in history—one after another, sometimes as many as four a year.

Come 1959, he could look back twenty years and see a punk kid with nothing but ambition to his credit, he could look back a decade and see a big star dumped by the world, or he could look into the mirror and see the most influential and talented popular entertainer of the century.

Now what?

Frank was to become such a colossus of American popular culture that it would’ve been crazy in his heyday to think of him as needy. But his heroic Last Honest Man posture always had as a counterpart a little boy’s thirst for camaraderie and love. “I don’t think Frank’s an adult emotionally,” his friend Humphrey Bogart sniffed. Shirley MacLaine was more clinical, calling Sinatra “a perpetual performing child who wants to please the mother audience.”

Never mind all the gruff stuff offstage: The evidence of what was in his heart was in his art. Here was a man who lived amid an entourage that could expand, if he wished it to, to infinity, a man who had virtually every woman he ever desired, a man for whom no material comfort was unattainable; yet his music was at its richest and most intense when he sang piteously about loneliness. His familiar swinging cockiness would be overwhelmed by a gray, anguished fog hovering over a profound, hollow core—the achy soul of the Tender Tough. “I’ll Be Seeing You,” “These Foolish Things,” “Guess I’ll Hang My Tears out to Dry,” “In the Wee Small Hours,” “Angel Eyes,” “What’s New?,” “One for My Baby”—a world of crushed dreams, blasted hopes, distant, impossible romance. People called it suicide music and couldn’t understand why he slowed down every show to perform it—sometimes exclusively. But loneliness was the most vibrant color in his musical palette, and it obviously came from someplace very deep inside of him.

Indeed, he was born to it. He was, of course, an only child—try to name another Italo-American only child of his generation!—and grew up with a yearning for the companionship that his friends, neighbors, and cousins all enjoyed in their homes. The cash and clothing that his mother lavished on him were his first means of acquiring a society: He handed down suits to kids whose friendship he courted; he bought burgers and candy and comic books, cultivating early on a habit of “gifting”—treating the house to drinks or meals or clothes or women or more. The assets Dolly spotted him as a teenager—his wardrobe, his car, his sheet music arrangements, his portable sound system—they were a way for him to get a leg up in show business, true, but they were also a means of being part of a bigger group.

Which is what made it so perfect that Sinatra came into his own as a performer during the big band era, when a singer was by necessity a piece of a large, vibrant whole. The Harry James and Tommy Dorsey bands were like big clubs of chums for him—and he didn’t have to buy his way in, either. He gorged himself on the grand bonhomie that the bands instantly provided him—the card games, hazing, drinking, dreaming, and bonding that he and his fellow musicians engaged in during endless bus rides. He was like a congenital junkie who became addicted with his very first hit. As soon as he’d begun life in that dazzling musical fraternity, he wanted to live no other way.

Witness his recollection of the day on which he left James for Dorsey: January 1940, Buffalo; the James band was headed to Hartford; Frank would briefly visit New York, then join Dorsey in Rockford, Illinois; it was the single big break of his career, and he’d yearned for it and schemed to make it so; still, he struggled through the separation from his bandmates of a mere six months: “The bus pulled out with the rest of the boys at about half-past midnight. I’d said good-bye to them all, and it was snowing, I remember. There was nobody around and I stood alone with my suitcase in the snow and watched the taillights disappear. Then the tears started and I tried to run after the bus.” (This was, keep in mind, a married man with a child on the way.)

Of course, the Dorsey band was to offer Frank the same sort of companionship he enjoyed with James. Moreover, Dorsey himself would come to serve as a hero and model for his young singer; Frank dressed and spoke like him, he studied his famous breathing technique, he even took up his hobby of model railroading. Still, even with the prospect of a new gang of buddies assured him, he arrived in Illinois with the beginnings of his own coterie, a safeguard against ever finding himself staring longingly at the receding taillights of a bus again: Nick Sevano, a Hoboken haberdasher who dressed him, did his errands, and even lived with him and his family when they weren’t on the road, and Hank Sanicola, accompanist, business manager, and, as his girth suggested, sometime thumbbreaker.

Two years later, when the allure of profits and aesthetic freedom drove Sinatra to seek his release from the Dorsey band, he was, once again, bereft of bandmates, so he gathered to his bony bosom a band, of sorts, of his own. He expanded his entourage to include such semiregulars as Mannie Sachs, a Columbia Records executive; Ben Barton, his music publisher and business partner; composer Jimmy Van Heusen; lyricist Sammy Cahn; bruisers Tami Mauriello and Al Silvani; and Jimmy Taratino, a boxing writer whose mob ties eventually formed a costly web for the singer. And he gave them all, guilelessly, a name: the Varsity.

En masse, the Varsity hit all the swell spots—nightclubs, saloons, showbiz eateries, and, especially, the Friday night fights at Madison Square Garden, where they mingled with mobsters, Times Square sharpies, and other supernumeraries of the fight game. Grown men actually vied to be admitted to their numbers, but that privilege was rarely granted, and the resultant loyalty of its members was embarrassingly high: When Mauriello was inducted into the service and sent overseas to fight, he gave Frank his golden ID bracelet, which the singer wore with puppy-dog pride.

After the war, the Varsity evolved, with some members resuming their lives without Frank (not always peaceably or voluntarily) and others accompanying him out West, where he had joined the extended family of MGM studios. There was a Softball team—Sinatra’s Swooners, with uniforms and cheerleaders (and Ava Gardner as, ahem, honorary bat girl); there were card games, pub crawls, the works.

But then the spiral that demolished his career began: Divorced, his voice uncertain, his name connected with reds, hoods, and a dozen drunken little fistfights, without a record company, film contract, or agent to call his own, he suddenly didn’t seem like a Sun King anymore. A few steadfast partisans held on; the larger crowd vaporized.

It was a subtle thing: People didn’t so much snub Frank as stop courting him. He couldn’t get tables in the same restaurants, or not the same tables, anyway. He couldn’t round up a poker game or gang of drunks to obliterate a night with him. Early one morning at the dawn of the fifties, Sammy was walking through Times Square, overjoyed with just having been allowed to break the color barrier long enough to schmooze with the big stars at Lindy’s. He passed the Capitol Theater—the place where Frank had once hired him and his dad and uncle when they were still unknown—and lo, there Frank was, walking along with a wounded air.

“Not a soul was paying attention to him,” Sammy recalled later. “This was the man who only a few years ago had tied up traffic all over Times Square. Thousands of people had been stepping all over each other trying to get a look at him. Now the same man was walking down the same street and nobody gave a damn.”

Читать дальше