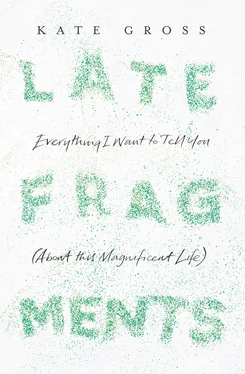

I imagine my own desperate appliance as a particularly inept vigilante marauding through my body on the hunt for cancer cells. He shoots – he kills! Oh no. More often than not, what he has slaughtered is a perfectly healthy cell just going about its taste-creating, nausea-controlling, body-hydrating business. Chemo is all about this clumsy collateral damage and how to manage it: hence the phalanx of steroids, anti-nausea pills and so on, each of which brings its own wicked side-effects. But what I hadn’t reckoned with was the mental stuff. My vigilante seems particularly adept at shooting down serotonin, so that for a few days the chemicals replace my soul with a shrivelled black void. With each cycle the physical and emotional scar tissue deepens. I elect to return, but only just.

If I wasn’t accompanied by my very own Terracotta Army of friends, returning to the chemo ward would be harder. They make things bearable. They understand the little things. That, even facing death, for me (like Hillary Clinton and her scrunchies) it’s still all about the hair (and lack thereof). That seeing the oncologist is easier when I’m in a tough-girl leopardskin coat with a slick of bright red lippy. That though my heart’s desire cannot be granted, that doesn’t mean I don’t desire stuff. The ancient Egyptians had it right – the urge to accumulate beautiful treasures increases the closer you get to death; and I intend to go into the afterlife looking polished, surrounded by the luxury goods given to me by the best women. They understand the big things too: how I need to live in Technicolor in the time I can. They plan holidays. We visit Paris in the rain. They take me to the newest restaurants, and send me extravagant bunches of flowers and richly scented candles so that in the evening I can draw the curtains and pretend that everything is just fine .

I sometimes sit in my chair, too tired to move, too brain-dead to read or write. With my eyes closed, I feel a pleasant weight pressing on my shoulders. It is the weight of all the time Billy and I have had with our friends, enveloping me like a heavy blanket. They are brave, these people. They were there the day after I was diagnosed, uninvited, hugging Billy and regaling me with tales of dreadful in-laws that made me laugh so much my new scar throbbed through the morphine. They are there when I come out of the claustrophobic scanning machines, squeezing my hand as I fretfully try to interpret every look the radiographers give each other. They arrive at our door with elaborate dishes for lunch, and then stay to do the washing up. Part of the reassuring weight I feel from these friendships comes from the discussions we have had about Afterwards. These are the kind of friends who want to be in my children’s lives forever. The kind of friends who will buy seven-seater cars to ferry them around as well as their own families. The kind of friends who will tell stories of Mummy long after she’s gone. The kind of friends who will pick Billy up when gritting his teeth and saying tomorrow will be a better day just doesn’t cut it.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)