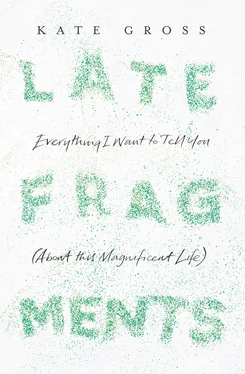

Together, we were an unstoppable force. Our grubby insecurities and doubts were lost in a haze of cigarette smoke and weak lager, surrendered to the noise of the college jukebox as we shook our cheaply-clad bottoms to the sounds of Nineties girl power. We took our terrible haircuts around the world for adventures; squashed them next to chickens and market ladies in day-long bus journeys; showed them off in the big city in summer temping jobs; flattened them under hats in ski season. When we weren’t together, we spent our time writing endless email epistles to one another, recounting tales of our disastrous love lives, moaning about our parents, and generally avoiding the data-entry jobs we were being paid to do in the stifling heat of summer in the city.

While other relationships might define us more – with our parents, partners, or children – for me female friendship has been the steady tick-tock of adult life. And maintaining these friendships over decades was a sign that, finally, I knew who I was inside. The fine thread between myself and my self had thickened and settled. I was one with me.

I wonder what it is about women’s friendship that is so important. A thousand glossy-magazine articles on the subject haven’t helped answer this question. I think conversation is at the heart of it, and it is certainly a truism that there is a lot of verbiage when this particular estate is gathered. Some themes are rather ubiquitous, like a song we keep remixing over the years. Our bodies, whether our thighs look like sausages in leather(ette) leggings, how many sweets have been consumed in the past twenty-four-hour period, whether anyone can see the new-found hairs under our sagging chins. We peer into other people’s lives, and yes, we can still be mean girls when we do this. We talk about men, of course. Back in the day, ‘Is he into me?’ (Usually with an inverse relationship between how into you he was and how much you talked about him.) Now, more mundane: ‘How can I teach him to see dirt?’ ‘Whither the romantic mini-break of old?’ I find that parents, and especially mothers, get a decent crack of the lady-chat whip. Children get a look-in too, but not till they are either wanted or have arrived. To the outsider listening in to our discussions, our world might appear limited, narrow, superficial. But listen more carefully. These discussions are just the bacon fat in the stew. They bring things together, keep the friendship well lubricated, make everyday fodder tasty. But without the rest of the conversation that this intimacy permits – the big discussions about life and our place in the world – our friendships would be no more than the dreadful pass-the-time chats had at the back of toddler groups.

I cannot speak here for friendship between men. It is not within my jurisdiction. Billy has been known as the most over-friended man in Britain, and as someone who exercises no judgement at all over his friendships. Perhaps the two are connected. In any event, his smiley face and enjoyment of whisky have gathered around him a bunch of people nearly as interesting, funny and kind as my own friends (some of them I love enough to winkle away and add to my entourage). I don’t know what binds him to his menfolk. I don’t pretend to understand what they talk about when I’m not there. My suspicion is that they have their own kinds of conversational bacon fat, perhaps revolving around electronic gadgetry, sex and bottom jokes – but like the female equivalent, it is just the grease in the engine of the more profound discussions.

These discussions are the other side of friendship. The conversations and the memories and the fun you have together permit you to reveal the weak, scared vulnerable self that emerges every now and again. My second operation – the one I had to chop the pesky tumours out of my liver, six months after my diagnosis and my first op – was tough. It took place in a shiny, cancer-defeating factory in Houston, because Billy’s careful research had shown that it had the best chance of successfully ridding me of cancer. We spent nearly a month there, and Stateside I was the glummest of glum girls. The operation depleted me in a way I could never have imagined. Agonisingly painful. Full of complications and miserable rehospitalisations. I finally returned home feeling drained of everything, including optimism. This was ironic, as post-operation I was in a better place, statistically, than I’d been since my original diagnosis six months previously: my odds of surviving the next five years leapt (briefly) from 6 per cent to 50 per cent. And yet for me it was the darkest part of the night. Maybe because everyone breathed a sigh of relief, and thought the crisis was over. Maybe because I was physically weaker than I’ve ever been. I don’t know why, but for several months there was a loneliness to my sadness which I hadn’t experienced before.

In that kind of situation, there are two options. The first is to battle through on your own. To grit your teeth, put your head down, and say things will be better tomorrow (whenever tomorrow comes). I call this the Scarlett O’Hara; it is a noble approach, one I’ve taken before, and one that I know appeals to the proud, quiet, maybe more masculine side of all of our natures. But I chose the second option, which was to write a list of my best women, and ask them to come and help. We sat in the garden. The tulips were out, and I howled snottily on their shoulders in a way I hadn’t before. After that I told them about my fears and loneliness, and how bloody awful everything had been. Then things got better.

Not long before the Nuisance, my fear had been that the really good times were over for these wonderful friendships. Thirty-somethings with children, jobs and partners to attend to, we were no longer as available to one another as we used to be. While I might wish we all lived in some kind of giant child-rearing commune, that isn’t the case. Friendships survive on scraps of time and emails, squeezed between the rest of life, and very often conducted thousands of miles apart. We live off well-trodden stories, the space in our lives for making new memories mostly taken up by family and work, where the real drama happens. The odd dinner, more often a cup of tea balanced precariously over a baby’s head while we converse, but never enough time for the real stuff, or for new adventures together. I always hoped there would be time for that again, if only in the Home for Neglected Mothers of Sons in which we would end up in our dotage. But now it seems that I won’t be checking into that particular nursing home. All the same, there is a happy postscript to this story, at least in Nuisance land. As one of these wise women says, quoting Mike Tyson, ‘Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face.’ We all had our plans. Our paths criss-crossed as we got on with life, friendships always there when they needed to be picked up. But then my family got punched in the face, far earlier and far harder than we could have expected, and our plans melted away. Suddenly time was carved out for friendship again. So cancer has given as well as it has taken – though perhaps it is more accurate to say that our friendships take from it what they can, a collective two fingers to all the Nuisance stands for.

I have spent so much of the past few years under the spell of chemotherapy, existing in a half-life where every fortnight is split into seven days of misery and seven days of life. Aside from (temporarily) taming my cancer, the other benefit of having this wicked set of toxins poured into me is that I see more of my resplendent friends from around the world than I have done for years. I am accompanied into the chemo ward. I am visited at home. This is lucky, because ‘therapy’ is a complete misnomer for the cruel concoction of drugs which is infused into my bloodstream in an attempt to keep me alive. But it has to be done: as Claudius puts it in Hamlet , ‘Diseases desperate grown by desperate appliance are relieved, Or not at all.’

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)