JULIET MARILLIER

Daughter of the Forest

Book One of the Sevenwaters Trilogy

To the strong women of my family:Dorothy, Jennifer, Elly and Bronya

Cover

Title Page JULIET MARILLIER Daughter of the Forest Book One of the Sevenwaters Trilogy

Dedication To the strong women of my family:Dorothy, Jennifer, Elly and Bronya

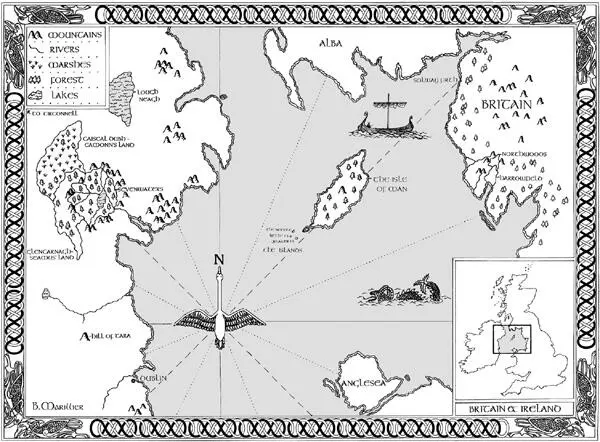

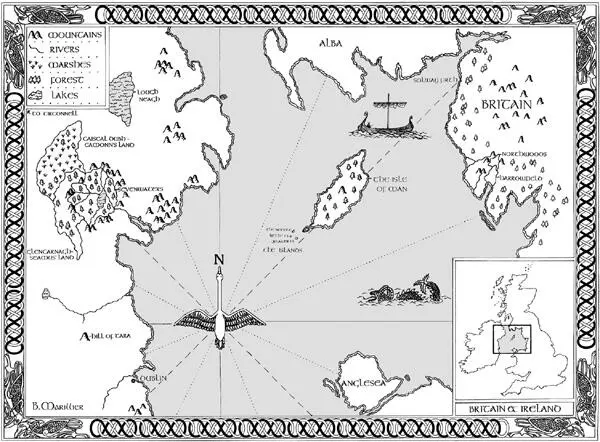

Map Map

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Preview

About the Author

Author’s Note

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Three children lay on the rocks at the water’s edge. A dark-haired little girl. Two boys, slightly older. This image is caught forever in my memory, like some fragile creature preserved in amber. Myself, my brothers. I remember the way the water rippled as I trailed my fingers across the shining surface.

‘Don’t lean over so far, Sorcha,’ said Padriac. ‘You might fall in.’ He was a year older than me and made the most of what little authority that gave him. You could understand it, I suppose. After all, there were six brothers altogether, and five of them were older than he was.

I ignored him, reaching down into the mysterious depths.

‘She might fall in, mightn’t she, Finbar?’

A long silence. As it stretched out, we both looked at Finbar, who lay on his back, full length on the warm rock. Not sleeping; his eyes reflected the open grey of the autumnal sky. His hair spread out on the rock in a wild black tangle. There was a hole in the sleeve of his jacket.

‘The swans are coming,’ said Finbar at last. He sat up slowly to rest his chin on raised knees. ‘They’re coming tonight.’

Behind him, a breeze stirred the branches of oak and elm, ash and elder, and scattered a drift of leaves, gold and bronze and brown. The lake lay in a circle of tree-clothed hills, sheltered as if in a great chalice.

‘How can you know that?’ queried Padriac. ‘How can you be so sure? It could be tomorrow, or the day after. Or they could go to some other place. You’re always so sure.’

I don’t remember Finbar answering, but later that day, as dusk was falling, he took me back to the lake shore. In the half light over the water, we saw the swans come home. The last low traces of sun caught a white movement in the darkening sky. Then they were near enough for us to see the pattern of their flight, the orderly formation descending through the cool air as the light faded. The rush of wings, the vibration of the air. The final glide to the water, the silvery flashing as it parted to receive them. As they landed, the sound was like my name, over and over: Sorcha , Sorcha . My hand crept into Finbar’s; we stood immobile until it was dark, and then my brother took me home.

If you are lucky enough to grow up the way I did, you have plenty of good things to remember. And some that are not so good. One spring, looking for the tiny green frogs that appeared as soon as the first warmth was in the air, my brothers and I splashed knee deep in the stream, making enough noise between us to frighten any creature away. Three of my six brothers were there, Conor whistling some old tune; Cormack, who was his twin, creeping up behind to slip a handful of bog weed down his neck. The two of them rolling on the bank, wrestling and laughing. And Finbar. Finbar was further up the stream, quiet by a rock pool. He would not turn stones to seek frogs; waiting, he would charm them out by his silence.

I had a fistful of wildflowers, violets, meadowsweet and the little pink ones we called cuckoo flowers. Down near the water’s edge was a new one with pretty star-shaped blooms of a delicate pale green, and leaves like grey feathers. I clambered nearer and reached out to pick one.

‘Sorcha! Don’t touch that!’ Finbar snapped.

Startled, I looked up. Finbar never gave me orders. If it had been Liam, now, who was the eldest, or Diarmid, who was the next one, I might have expected it. Finbar was hurrying back towards me, frogs abandoned. But why should I take notice of him? He wasn’t so very much older, and it was only a flower. I heard him saying, ‘Sorcha, don’t –’ as my small fingers plucked one of the soft-looking stems.

The pain in my hand was like fire – a white-hot agony that made me screw up my face and howl as I blundered along the path, my flowers dropped heedless underfoot. Finbar stopped me none too gently, his hands on my shoulders arresting my wild progress.

‘Starwort,’ he said, taking a good look at my hand, which was swelling and turning an alarming shade of red. By this time my shrieks had brought the twins running. Cormack held onto me, since he was strong, and I was bawling and thrashing about with the pain. Conor tore off a strip from his grubby shirt. Finbar had found a pair of pointed twigs, and he began to pull out, delicately, one by one the tiny needle-like spines the starwort plant had embedded in my soft flesh. I remember the pressure of Cormack’s hands on my arms as I gulped for air between sobs, and I can still hear Conor talking, talking in a quiet voice as Finbar’s long deft fingers went steadily about their task.

‘… and her name was Deirdre, Lady of the Forest, but nobody ever saw her, save late at night, if you went out along the paths under the birch trees, you might catch a glimpse of her tall figure in a cloak of midnight blue, and her long hair, wild and dark, floating out behind her, and her little crown of stars …’

When it was done, they bound up my hand with Conor’s makeshift bandage and some crushed marigold petals, and by morning it was better. And never a word they said to my oldest brothers, when they came home, about what a foolish girl I’d been.

From then on I knew what starwort was, and I began to teach myself about other plants that could hurt or heal. A child that grows up half-wild in the forest learns the secrets that grow there simply through common sense. Mushroom and toadstool. Lichen, moss and creeper. Leaf, flower, root and bark. Throughout the endless reaches of the forest, great oak, strong ash and gentle birch sheltered a myriad of growing things. I learned where to find them, when to cut them, how to use them in salve, ointment or infusion. But I was not content with that. I spoke with the old women of the cottages till they tired of me, and I studied what manuscripts I could find, and tried things out for myself. There was always more to learn; and there was no shortage of work to be done.

When was the beginning? When my father met my mother, and lost his heart, and chose to wed for love? Or was it when I was born? I should have been the seventh son of a seventh son, but the goddess was playing tricks, and I was a girl. And after she gave birth to me, my mother died.

It could not be said that my father gave way to his grief. He was too strong for that, but when he lost her, some light in him went out. It was all councils and power games, and dealing behind closed doors. That was all he saw, and all he cared about. So my brothers grew up running wild in the forest around the keep of Sevenwaters. Maybe I wasn’t the seventh son of the old tales, the one who’d have magical powers and the luck of the Fair Folk, but I tagged along with the boys anyway, and they loved me and raised me as well as a bunch of boys could.

Читать дальше