JULIET MARILLIER

Child of the Prophecy

Book Three of the Sevenwaters Trilogy

To old friends

Cover

Title Page JULIET MARILLIER Child of the Prophecy Book Three of the Sevenwaters Trilogy

Dedication To old friends

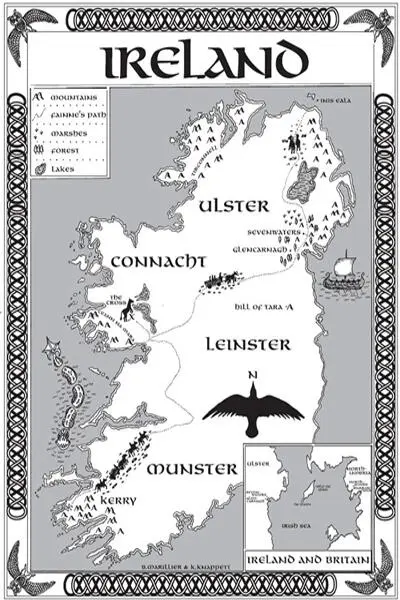

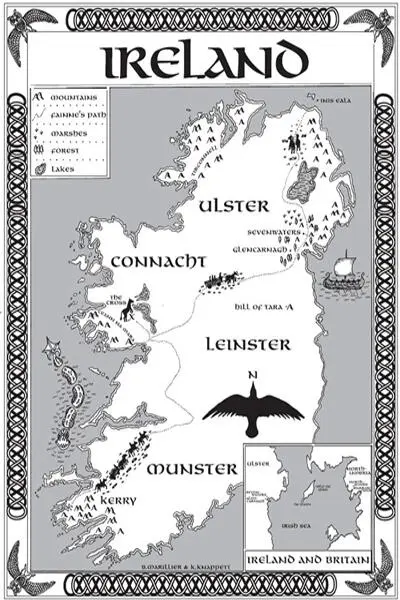

Map Map

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Afterword

About the Author

Praise

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Every summer they came. By earth and sky, by sun and stone I counted the days. I’d climb up to the circle and sit there quiet with my back to the warmth of the rock I called Sentinel, and see the rabbits come out in the fading light to nibble at what sparse pickings might be found on the barren hillside. The sun sank in the west, a ball of orange fire diving beyond the hills into the unseen depths of the ocean. Its dying light caught the shapes of the dolmens and stretched their strange shadows out across the stony ground before me. I’d been here every summer since first I saw the travellers come, and I’d learned to read the signs. Each day the setting sun threw the dark pointed shapes a little further across the hilltop to the north. When the biggest shadow came right to my toes, here where I sat in the very centre of the circle, it was time. Tomorrow I could go and watch by the track, for they’d be here.

There was a pattern to it. There were patterns to everything, if you knew how to look. My father taught me that. The real skill lay in staying outside them, in not letting yourself be caught up in them. It was a mistake to think you belonged. Such as we were could never belong. That, too, I learned from him.

I’d wait there by the track, behind a juniper bush, still as a child made of stone. There’d be a sound of hooves, and the creak of wheels turning. Then I’d see one or two of the lads on ponies, riding up ahead, keeping an eye out for any trouble. By the time they came up the hill and passed by me where I hid, they’d relaxed their guard and were joking and laughing, for they were close to camp and a summer of good fishing and relative ease, a time for mending things and making things. The season they spent here at the bay was the closest they ever came to settling down.

Then there’d be a cart or two, the old men and women sitting up on top, the smaller children perched on the load or running alongside. Danny Walker would be driving one pair of horses, his wife Peg the other. The rest of the folk would walk behind, their scarves and shawls and neckerchiefs bright splashes of colour in the dun and grey of the landscape, for it was barren enough up here, even in the warmth of early summer. I’d watch and wait unseen, never stirring. And last, there was the string of ponies, and the younger lads leading them or riding alongside. That was the best moment of the summer: the first glimpse I got of Darragh, sitting small and proud on his sturdy grey. He’d be pale after the winter up north, and frowning as he watched his charges, always alert lest one of them should make a bolt for freedom. They’d a mind to go their own way, these hill ponies, until they were properly broken. This string would be trained over the warmer season, and sold when the travelling folk went north again.

Not by so much as a twitch of a finger or a blink of an eyelid would I let on I was there. But Darragh would know. His brown eyes would look sideways, twinkling, and he’d flash a grin that nobody saw, nobody but me where I hid by the track. Then the travellers would pass on and be gone down to the cove and their summer encampment, and I’d be away home, scuttling across the hill and down over the neck of land to the Honeycomb, which was where we lived, my father and I.

Father didn’t much like me to go out. But he did not lay down any restrictions. It was more effective, he said, for me to set my own rules. The craft was a hard taskmaster. I would discover soon enough that it left no time for friends, no time for play, no time for swimming or fishing or jumping off the rocks as the other children did. There was much to learn. And when Father was too busy to teach me, I must spend my time practising my skills. The only rules were the unspoken ones. Besides, I couldn’t wander far, not with my foot the way it was.

I understood that for our kind the craft was all that really mattered. But Darragh made his way into my life uninvited, and once he was there he became my summer companion and my best friend; my only friend, to tell the truth. I was frightened of the other children and could hardly imagine joining in their boisterous games. They in their turn avoided me. Maybe it was fear, and maybe it was something else. I knew I was cleverer than they were. I knew I could do what I liked to them, if I chose to. And yet, when I looked at my reflection in the water, and thought of the boys and girls I’d seen running along the sand shouting to one another, and fishing from the rocks, and mending nets alongside their fathers and mothers, I wished with all my heart that I was one of them, and not myself. I wished I was one of the traveller girls, with a red scarf and a shawl with a long fringe to it, so I could perch up high on the cart and ride away in autumn time to the far distant lands of the north.

We had a place, a secret place, halfway down the hill behind big boulders and looking out to the south west. Below us the steep, rocky promontory of the Honeycomb jutted into the sea. Inside it was a complex network of caves and chambers and concealed ways, a suitable home for a man such as my father. Behind us the slope stretched up and up to the flattened top of the hill, where the stone circle stood, and then down again to the cart track. Beyond that was the land of Kerry, and further still were places whose names I did not know. But Darragh knew, and Darragh told me as he stacked driftwood neatly for a fire, and hunted for flint and tinder while I got out a little jar of dried herbs for tea. He told me of lakes and forests, of wild crags and gentle misty valleys. He described how the Norsemen, whose raids on our coast were so feared, had settled here and there and married Irish women, and bred children who were neither one thing nor the other. With a gleam of excitement in his brown eyes, he spoke of the great horse fair up north. He got so caught up in this, his thin hands gesturing, his voice bright with enthusiasm, that he forgot he was supposed to be lighting the little fire. So I did it myself, pointing at the sticks with my first finger, summoning the flame. The driftwood burst instantly alight, and our small pan of water began to heat. Darragh fell silent.

‘Go on,’ I said. ‘Did the old man buy the pony or not?’

But Darragh was frowning at me, his dark brows drawn together in disapproval. ‘You shouldn’t do that,’ he said.

‘What?’

‘Light the fire like that. Using sorcerer’s tricks. Not when you don’t need to. What’s wrong with flint and tinder? I would have done it.’

‘Why bother? My way’s quicker.’ I was casting a handful of the dry leaves into the pot to brew. The smell of the herbs arose freshly in the cool air of the hillside.

Читать дальше