Allowing for a few thousand neutrals at the game, a bare minimum of Magyar émigrés and a scattering of communist diplomats, some, say, 95,000 people went back to the workplaces, pubs and working-men’s clubs of an England approaching full employment and spoke about it. According to the old marketing principle that everyone knew 250 people – or, even if the number were pared to a conservative 100 – it meant that somewhere between nearly a quarter and over half of the population of England heard of the moment from someone they knew who had been there. This was in addition to what they discovered through the papers and radio. TV had missed the moment; only the second half was broadcast, because the FA didn’t want people staying away from several afternoon replays between lower division and non-league clubs in the second round of the Cup. But all channels of communication reflected on this matter of wide national concern. Scots, Welsh and Irish joined in, in appreciation as much as glee.

Puskas’s achievement was of mythical proportions. My dad talked about it with his brother and many other people. When he told me about it, I understood it to have been performed by someone from somewhere called ‘Hungry’. This put it in the same funny-country category as ‘Turkey’ and ‘Grease’, though it turned out to be not some old gag but a stroke of magic. Puskas, I gathered, rolled the ball beneath his foot backwards and forwards several times. This had cast a kind of spell on the England defence, as if they were under the influence of an old Indian snake-charmer like Dr Dadachanji. They had swayed back and forth with it, till Puskas’s final dispatch of the ball snapped them out of their trance. I practised rolling an old tennis ball under my foot in the backyard and tried it on the other kids in the infants’ playground. Far from mesmerised, they shouted at me to get on with it. It occurred to me this might not be my skill; also, that foreigners could do very impressive things.

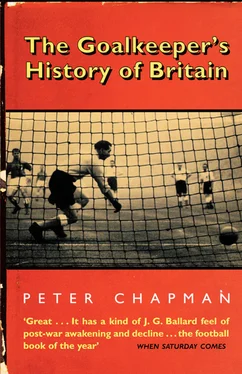

The Hungary defeat was not Merrick’s fault. He’d had to be necessarily spectacular to stop any number of Hungarian attacks. My encyclopaedia showed one, the England keeper springing left with rolled sleeves and black wool-gloved hand to push the ball around the post. A strand of dark brilliantined hair out of place confirmed the pressure he was under. Puskas said that if Merrick hadn’t played so well the score would have been 12.

By the time a quarter of that figure had been reached, the outcome was certain. We had been out-performed and the most implacable last line we could muster was unable to stop the foreign tide. As Puskas’s shot flashed by, Merrick’s raised hand clutched only a gloveful of November gloom. Half turning his head to watch the ball on its way into the net, his eyes were unmoved as ever, staring at the end of empire.

Chapter 5

Neck on the Block

We learned at school that the tree which best survived on the streets of London was the plane tree. For several years I assumed there was no other tree around, failing to register the chestnuts on the steep embankment of the canal and evidence from Sunday visits my mum organised to leafier places like Kensington and Hyde Park. The plane tree’s visible trick was to shed its bark regularly to shake off the effects of the London smog. But its secret lay in its name. It was the ‘good old’ plane tree, plain and straightforward as we were, a tree for the common man. It was strong and it survived.

Crossing Danbury Street on my way back home from school, about a week into 1954, it started to rain. The taps in the playground had been frozen, so I leaned my head back and for about twenty seconds drank from the sky. A few days later I was sent home from school early with a head like death. My stomach came out in sympathy. No one quite knew what it was as I was put in bed, but when my dad arrived back in the evening he recognised what was wrong from his time in Italy and Africa. He carried me to my grandad’s car and they took me to the children’s hospital in Hackney Road, which confirmed the problem as dysentery. I was kept in for three weeks and treated as if victim of a tropical disease.

My grandad generally had a ton of coal delivered just before winter started. The coalman, who wore a flat cap, trousers held up by braces and looked like he’d climbed out of the chimney, shot the 20 hundredweight sacks of the stuff down the coalhole in the pavement and into the basement area cellar. It shone in large, tar-laden chunks. After its dust was swept into the gutter, the stain in the paving stones remained for at least a day of rain. A month later the smog came down, from about the third week of November, and hung around on and off into February. You wore it as a badge of honour, a mark of living in the largest city in the world. The newspapers said that thousands of people with bronchitis and other illnesses died from it. When you put a handkerchief over your mouth, by the time you’d walked down the street and back, a wet, black mark had appeared. Many football matches would be abandoned, the ref finally giving up hope of an improvement some good way into the game. Every year there’d be one when, with the teams back in the dressing room, it would be realised a goalkeeper was missing. The trainer or a policeman would be sent out to find him, at the edge of his penalty area, peering into the smog, unaware everyone else had left the field. This happened to Ted Ditchbum, Sam Bartram and any number of them until the smog as an annual event finally disappeared.

Ours was the black ash variety, particles of the stuff floating before your eyes. The Americans came up with a new one. They carried out an H-bomb test on the Pacific island of Bikini. Japanese fishermen heard the explosion and saw the mushroom cloud rise from 80 miles away. An hour and a half later, it started to rain, or rather snow on them, a kind of white-ash smog – probably pieces of Bikini, as well as whatever else comprised such a phenomenon. Fortunately, the Americans were on our side (the Russians only had the A-bomb). My dad said the GIs he’d met abroad were as friendly as anyone you could come across. But despite the fact they spoke English, you couldn’t say they were exactly like us. Johnny Ray began a tour of Britain, smiled a lot and collapsed into tears at the end of his songs – nice, but funny people.

It was just as well that this time the USA were not among the teams in the summer’s World Cup finals. Neither England, nor Scotland (who turned up for the first time) needed the embarrassment. In an act of self-punishment that would have done Bert Williams proud, England chose to go for one of their warm-up games to meet the Hungarians, in the Nep, or People’s stadium in Budapest. A local reflecting on the occasion with British writer John Moynihan said he was amazed when England took the field: ‘We had always thought of them as gods. But they looked so old and jaded, and their kit was laughable. We felt sorry for you.’ That was before the kick-off. His sorrow had surely turned to Johnny Ray-like sobs by the final whistle. Hungary won 7–1.

In the World Cup in Switzerland, Merrick was blamed for three of the four goals Uruguay scored when eliminating England in the quarter-finals. Out of touch with home newspapers during the competition, he was surprised when a reporter asked him on his return whether he had any comment on having ‘let the country down’. He replied it was a ‘poor show’ if people had said that, that only the last Uruguay goal was his fault in a 4–2 defeat and that none of his teammates had blamed him.

Actually, Stanley Matthews – often cast as one of football’s ambassadors – commented that Merrick ‘disappointed’ us ‘when we were playing well and had a chance’. This in itself showed a new feeling towards the tournament. In Brazil four years earlier the players had given the impression they couldn’t have cared less. Suddenly they wanted to win. After the years of suspicion towards a ‘foreign’ trophy, it was at least a tentative advance from the line into territory mapped out by others.

Читать дальше