There was some confusion over the men who had reached the summit. Neither was British. As a New Zealander, Edmund Hillary was almost, but not quite. Our butter came from New Zealand and had a picture of a kiwi stamped on the wrapping. New Zealanders were called ‘kiwis’. The fellow who went to the top with him clearly wasn’t British. He was Sherpa Tensing. ‘Sherpa’ was the name of the group, like a tribe, he belonged to; his name was Tensing Norgay. The BBC and everyone called him ‘Sherpa Tensing’. They could, by the same token, have referred to his partner at the summit as ‘Kiwi Edmund’.

The Sherpas were loyal and trusty, a bit like the Gurkhas who fought with the British army. My dad had a kukhri, one of the Gurkhas’ curved knives, in a leather sheath on a shelf in the sitting room. This one was blunt but a frightening-looking thing. You were glad these people were on your side. The Gurkhas were from a similar part of the world, but the Sherpas lived at the foot of Everest itself and were mountain guides. Amazingly, they were guides who hadn’t been to the top of the mountain themselves. Their god had forbidden them to do so, we learned. Only on our authority, it followed, had they been happy to ignore his ruling. It was a mark of how loyal and trusty they were. They’d just been waiting for us to come along and lead them to the conquering heights.

There lay the answer to my early confusion. Two non-British types had reached the summit but the conquest was ours. It was a British expedition. A little down the mountain was its British leader, John Hunt, who had selected the two to go to the top. He could have chosen himself but it was to others we allowed such honours. We took quiet satisfaction from knowing that without us it wouldn’t have been possible. As on Everest, we led by rock-like example, uninterested in public glory. Britain’s role was naturally that of the man at the back.

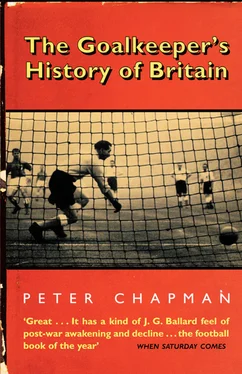

There was no one more natural in the role than Gil Merrick. He had been born to the position upon which everything depended. He was the sort of person who exemplified our response to a threatening world. He faced it as we would, quietly and calmly, and if not to win every title on offer abroad, then at least to stay unbeaten at home.

The first challenge of the autumn was to be the game staged for the FA’s ninetieth anniversary. The team sent along in October by Fifa as the ‘Rest of the World’ wasn’t exactly that. The Latin Americans found it too difficult to travel half the globe in boats and planes for this one game alone. But with a collection of mainly Austrians and Yugoslavs, plus a Swede, German, Italian and a Hungarian-born Spaniard to make up the number, it would represent a good test of our renewed confidence in our game and the forces of the universe.

An Austrian, Willy Meisl, a journalist whose brother Hugo had been the goalkeeper of the 1930s’ ‘Wunderteam’, was given the honour of writing an introductory note in the Wembley programme. True to the character of such people, he abused it. It had long been recognised in other countries, he said, that ‘there was little hope of defeating a British national team by orthodox tactics on its home ground’. The Rest of the World would employ Austria’s methods of an attacking centre-half and ‘charmingly precise, short-passing game’.

This was boastful of him, as well as mischievous to suggest that the ‘orthodox’ way was itself a form of ‘tactics’. Right-minded people knew it was the right way to play. He showed further bad grace in suggesting that although England might be getting used to such ‘tricks’ as tactics (he used quote marks to suggest he didn’t really think they were tricks), its teams were ‘so stereotyped’ that they were ‘still prone to be baffled when unusual methods are introduced’. In response, they could only play a hard physical game and get ‘stuck in’. It was ‘why the true craft of soccer has experienced a decline in the game’s homeland’ he claimed, concluding that the Rest of the World would prove superior on the day. But England’s fighting power might achieve a 2–2 or 3–3 draw.

Shoddy though his intentions were, his forecast proved almost correct. The Rest of the World were 4–3 up with one minute to play when England fortunately won a penalty. Some said the referee’s decision was dubious. But Mr B. W. Griffiths was a transparently neutral Welshman who had served in the RAF during the war. He’d been a sergeant-instructor and was now a schoolteacher, a stickler for doing it by the book. In 1950 he’d been among the first British referees to officiate at a World Cup and seen at close hand the tricks foreign defenders got up to. They needed watching. Besides, there was an order to be upheld here. England and Tottenham full-back Alf Ramsey, a man with a stomach for the occasion, strode up to take the penalty kick and drove the equaliser home from the spot.

The crowd had been in such a state of cliff-hanging excitement that they’d probably forgotten the advertisements in the programme for Wembley’s forthcoming attractions. England’s next opponents at the ground in one month’s time were to be the Olympic gold medallists, Hungary. They figured modestly on the page of events on offer. At the top was an ice hockey match between Wembley Lions and Harringay Racers in the Empire Pool (seat prices from half a crown to twelve and sixpence); next, tournaments of amateur boxing and ‘indoor lawn tennis’. The Hungary game – for 25th November, kick-off 2.15 p.m. – was then mentioned, but in far less space than the ad for the imminent start of the year’s pantomime season. Understandable, really, since as a spectacle it would surely not rate with ‘Humpty Dumpty on Ice’.

On the day itself, the programme notes did anticipate a significant contest. At the Helsinki Olympics the year before, the Hungarians had beaten Yugoslavia 1–0 in the final. They were, of course, among the communist countries making a mockery of what should have been the thoroughly amateur Olympics. Their players claimed to have jobs outside football. Hungary’s captain, Ferenc Puskas, was an army officer, the ‘galloping major’. He would be marked in one of the day’s crucial battles by England’s captain and ‘human dynamo’ Billy Wright. Centre-forward Nandor Hidegkuti and goalkeeper Gyula Grosics were ‘clerical workers’. Centre-half Jozsef Bozsik was to set a Wembley record as ‘the first Member of Parliament ever to play in an International match upon the famous pitch’. He was member for one of the Budapest constituencies, whatever that meant in a totalitarian state. No one was fooled. They were full-time footballers.

Their beautiful football in Helsinki, said the programme, had made them famous the world over. They were unbeaten in the past two seasons. One note, which had a 1066-and-all-that ring to it, went so far as to say that this was the day ‘England faces perhaps the greatest challenge yet to her island supremacy’. To meet it, Gil Merrick was cast in a classical role; he was Horatius facing the Etruscan hordes across the Tiber: ‘It may well be his duty this afternoon to show that unspectacular anticipation is the best weapon of all to hold a heavily attacked bridge.’

But this was to get things out of proportion. Others had been and gone before this lot, the cherry-shirted Hungarians, all continental short shorts and short passing game. The privilege of writing in the programme on how the match might go was not given this time to any cheeky foreigner but to the football correspondent of the London Evening Standard, Harold Palmer. In a half-century or so, he noted, fourteen foreign international sides had been seen off. Hungary had been among them, losing 6–2 at Highbury in 1936. It wasn’t that they hadn’t been a clever team, Palmer conceded with magnanimity, and they had even been superior in midfield. They’d just lacked that component of seeing things through. Having got so far, they ‘let themselves down by their weakness in front of goal’.

Читать дальше