The menace of tactics was obvious but it was difficult to know what to do about it. In the absence of clear thinking, it was decided to ignore it. Resolve and character would have to do. An empire had been built on them. Britain lost ‘every battle but the last’. There were no defeats, merely setbacks ‘on the road to eventual victory’. Actually, it was Karl Marx who said something like that, the fellow who had claimed that by bringing the railways to India, Britain had only laid down the iron path of Indian revolution. Off the rails though he was, he’d done his best work in Bloomsbury, in the British Museum, a few streets from where my nan had been born off Theobald’s Road. Lenin had lived in Finsbury for a while, just north past the end of Exmouth Market. He’d have walked along it, as my grandad and great-grandma served up carved roasts to the poor and workers of the area, and around the streets of Clerkenwell en route to his own eventual victory. Marx and he would have picked up some of the grit and mood in the air.

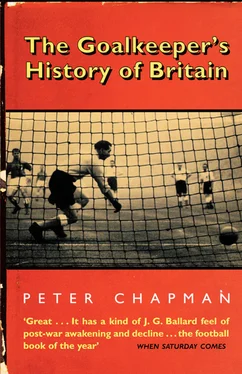

It wasn’t that foreigners like them, or any other, were not clever people. Tactics, whatever you felt about the morality of them, showed they could be. But could their keepers calmly catch a ball? Would they take a cross, with the pressure really on? They were form rather than content, capable of something thrillingly dangerous or elaborate but impossible to sustain. Foreigners couldn’t ‘hold the line’; they couldn’t see things through.

Churchill saw through the Labour Party as soon as he was back in Downing Street. Our position slipping, they’d tried to stop anything that might be construed as our retreat from greatness by quietly taking us down the nuclear path. Churchill didn’t mind, he just wished he’d been told. He soon visited the USA to push his arguments for the alliance of English-speaking peoples, our special relationship. It was the alternative to dealing with the chaotic Europeans. The USA had always liked the cut of the old boy’s jib more than that Attlee fellow, with his pink ideas. In return for aid, Churchill said they could use our military bases for the two countries’ ‘common defence’. That’d hold the line.

On the customary end-of-season tour, in May 1952, England went to Italy. In the goalmouths of Florence stadium where my father had played before him, Merrick did his bit maintaining the score at 1–1. They travelled on to meet the Austrians again, in occupied Vienna. The game was played at the Prater Stadium in the Russian zone, but British troops packed the crowd. The forward line was led by Nat Lofthouse of Bolton Wanderers, a centre-forward in the old physical mould. Ocwirk’s mechanism failed to tick for the occasion, while Lofthouse so intimidated the Austrian keeper, Walter Zeman, that he scored two of England’s goals in a 3–2 victory.

Unintimidatable, Merrick had his best England game. He made the winning goal, rising to pluck a swirling corner kick from the angle of bar and post and clearing, via Tom Finney, to Lofthouse on the chase. Zeman came at him boots first – as Merrick noted, this was ‘the wrong way of going down at a man’s feet’. We went down with head and hands, bravely, either to smother the shot or pluck the ball from the rampaging opponent’s toe. Zeman’s feet laid out Lofthouse, but not before he slipped in the winner. The troops carried him off on their shoulders at the end, Lofthouse the ‘Lion of Vienna’. Merrick, however, quietly claimed a greater prize than a mere title. England field players kept their shirts from each game, but the keeper was never able to have his jersey. He had to hand it back to an FA checker perched over the kit basket; something about them being more difficult to obtain, thought Merrick. The feel of this one was like wearing ‘a special and expensive suit for the first time’. The mood in the dressing room was so jubilant that he asked if he could keep it and the ecstatic Winterbottom was happy to comply. ‘Do you wonder,’ said Merrick, still moved by the memory years later, ‘I treasure that jersey more than anything in football?’

For reasons I could never grasp, my parents were moved to take holidays on the continent – about once every four years, with a week at a holiday camp between times, while they saved the money. This was my mum’s doing. My dad – country boy, big family – would as happily have stayed at home. Before the war she’d taken a couple of day-trips to Ostend from Margate and a boat trip down the Seine for her fourteenth birthday. At work, Waterlows had organised a football tour to a small town near Ypres and she went as a spectator. That was Easter 1939; a member of the ship’s staff counting them off at the Ostend quayside said: ‘There’s more than ever now. Everyone thinks there’ll be a war.’ Then the civilian traffic stopped and my dad went in khaki. He wrote romantic letters back with sketches of happy soldiers jumping off landing craft on to beaches. The censor would let those through. My mum felt she’d missed out on the fun and dragged him back as soon as he was home. Much of Italy was destroyed. They hitched army trucks to get from Florence to Siena, wangled special visas to get to Trieste. This was thought very strange round our street.

When I went abroad at the age of three, the Channel was very rough. It always was. My parents said they’d been on one crossing when even the crew was sick. We stayed with my father’s friends in Siena in a small street behind the cathedral. It all seemed extremely poor. Aunts, nieces and grandmas competed to scrub my face at night and parade me back in front of the applauding family. It was very embarrassing. Trains were always late. There was a huge mob on Florence station, which my dad said would all leap through the open windows when the train came in to grab a seat. So, clever move, we stood on the platform behind a priest, our seating arrangements thus assured. When the train came in, he threw his suitcase through the window like the rest of them and, habit ascending, dived dramatically after it.

If it hadn’t been for the last game on the next summer tour – this time stretching itself to the newer frontiers of South America – England would have stayed unbeaten. Uruguay, the World Cup holders, won 2–1 in Montevideo. It was a pity but much too far away to matter. Of more immediate importance was the fact that the spring and summer of 1953 proved that reward came to those who stayed the course. Stanley Matthews received his winner’s medal at Wembley, with his last chance to appear in an FA Cup Final. His runs down the Blackpool right were defined as the thrilling difference in a 4–3 victory against Bolton Wanderers. That much of the score resulted from errors which would have disqualified either goalkeeper from appearing in the South East Counties League, was a detail laid aside in celebration of a long and distinguished career. A month later, Gordon Richards, unable to win a Derby in three brilliant decades in the saddle, did so at his final attempt. ‘It felt like it all came right,’ said my dad. There was a sense of justice and harmony to the world. Master the fundamentals and eventually the glorious moments would follow.

No one did either like we did. In June, who else could have staged a coronation in all that rain? Look at Queen Salote of Tonga, the only royal guest to ride with her carriage hood down, soaking Haile Selassie in the process. God bless her, people thought, for being such a good sort and showing why the empire was necessary in the first place. My fourteen-year-old Uncle Keith and I squelched around to the special school in Colebrooke Row, near the Manchester Union of Oddfellows, for our red jelly and pink blancmange. They were served in the hall, not the playground where the kids’ party was meant to be. It didn’t detract from the day. The national spirit had been buoyed that morning by the news we had conquered Everest. At least, that was as I understood it.

Читать дальше