1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...18 Across the dark sea the lights of the Water Village showed where Mabul lay and reminded Sarani of something that had been puzzling him.

‘Many tourists go there. Woi, many.’ I agreed. ‘I have seen many white people there, men and women, husbands and wives. But I have not seen children. How can this be? Do they not have children? Do they not sleep together?’

‘Of course there are children, but they do not always go with their parents.’

‘They leave their children behind? How can they do that? I could not do that. Arjan would just cry and cry.’ He thought awhile. ‘They have many children? As many as we do?’

‘Sometimes, but usually two, maybe three.’

‘So few? I had seven with my first wife and now three more. It’s a problem for me. I am old, and I have three young children. If they live, I don’t want to have any more. Minehanga doesn’t want to have any more. It is very difficult. I am still strong for playing love. How can they have so few?’

‘ Ada obat , there is medicine.’ Obat is a general word in Malay, and takes in herbal preparations and traditional cures as well as what a doctor would dispense. It can also include magic. His expression brightened.

‘ Obat kampung ? Village medicine?’

‘No, there is a pill.’

‘A friend told me this, but I did not believe him. And I can drink this pill?’ He was eager to join the fertility revolution however late in the game.

‘No, it is for the woman.’

‘Oh, I see. Can I find this pill in Semporna?’

I tried to picture Minehanga with a blister pack in her hand, popping a pill through the silver foil, remembering to do it every day, and could not.

‘It is not just one pill.’ I replied. ‘It is one pill every day and if you forget one day maybe it does not work. Maybe it is not good for Minehanga. But there is also medicine for the man.’

‘Oh? I drink this one?’

How to explain a condom? I did not even have the requisite vocabulary for the body parts involved. I improvised and came up with a gloss along the lines of a rubber sock that stopped the white water from going into the body of the woman. There was pointing involved, hand signals. Sarani got the message.

‘Do you have any of this medicine? Can I find it in Semporna?’

I found myself wondering how sexual relations were conducted in a communal living space, amongst sleeping children and relations, and the answer was: quietly. The boat rocking anyway, the planks creaking, who would notice?

Throughout our conversations Sarani appended the phrase ‘if they live’ to every mention of children. I could imagine infant mortality being high in this environment, but the way he said it was like touching wood, as though to expect them to survive were to be presumptuous. Maybe this was the thinking behind the casual attitude adults adopted towards children, paying them surprisingly little attention, trying not to become too fond of them in case they did not live.

The breeze died away. There were stars down to the edges of the sky, and the waxing moon rose massive on the horizon. In the calm, sounds came clearly from the other boats. Pilar was pumping out the bilge, the handle squeaking. The light from a hurricane lamp brightened to a glare in the stern of another boat where figures moved, lit from the waist down. The lamp was passed down into a dug-out and strapped to the bow. It moved slowly out over the reef. Other canoes followed.

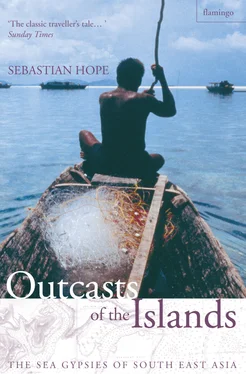

‘They are looking for cuttlefish. When the moon is bright, the cuttlefish come out. When there is no wind you can see into the water. If you have a lamp. Then you can spear cuttlefish and ray and trepang. If you have a spear. My lamp is broken. I have no spear. We cannot go.’ We watched as a canoe slipped past close by, a young man standing in the bow, poling with the blunt end of the spear, his face illuminated from below by light escaping around the metal lampshade. He was peering like a heron into the bright pool at his feet. The shadow of the keel passed over the sand in a halo of light, exaggerating the colours of the red and orange starfish that had crept up on us with the tide. A long-tom burst from the edge of the lighted circle and we could hear it skipping away into the darkness.

‘You can catch long-tom at night, but not with a spear,’ Sarani said. ‘They are frightened of the light. If the light touches them, they run. You can catch them with a net, a different net that floats right at the surface. If you have a flashlight, you can sweep it across the water, you see, and drive them towards the net. But they can be dangerous. Their nose is very sharp. When I was still strong, in the Philippines, a man was hit by one.’ He was laughing now, and the rest of the story had to wait until he could keep a straight face. ‘You see, he was fishing at night, and another canoe came close to him, and a long-tom ran straight at his boat. It stuck in his leg like a spear. He was so angry he took his parang and cut the long-tom up into little pieces and burnt it on the fire until it was only ashes. He walked with a limp after, but he had luck he was not sitting down or he would be dead.’ He laughed again. ‘You see, a dangerous fish, but good to eat.’

I kept Sarani company until the tide fell and he could complete his last chore of the day. He slipped into the water and I passed down the props to him. He wedged them under the gunwales with his foot. He changed into a dry sarong and chewed a last wad of betel while he pumped out the bilge. He settled down next to Minehanga. They exchanged mumbled words. I stayed on the bow a while longer, drinking in the peace and the solitude, the lights on the reef like floating stars, a road of moonlight across the water.

Watching the net come into view I sensed again the excitement I had felt as a boy pulling up a lobster pot in Donegal. My father would set them close in to Loughros Point and it would be my job to pull them up, while he kept us off the rocks. The pot would emerge like a coffer from the deep, shimmering, magnified, full maybe.

There was a long pull before the first fish appeared in the net, a glint of silver blue light from way below where the net’s parabola could last be seen, the pure white belly of a ray. More were following. Pilar gripped them by the eye sockets, which offered the only safe purchase on the streamlined body, and pulled them through the mesh of the net, throwing them into the corner between gunwale and splashboard, right below where I sat. I watched the heap grow, olive-brown ray with light blue spots flapping their wings on the deck. Some landed on their backs, mouths working, the gill vents opening and closing, seeming to sigh.

We netted fourteen in all, but Sarani was not happy. ‘Before, we could catch forty or fifty ray in one netting. Now, you see, how many tails? Kami rugi, ba . In the market we sell three tails for two ringgit (50p). This catch is less than ten ringgit. And how many ringgit of oil did we use? Going and returning putting down the net, going and returning pulling it up, maybe five ringgit over. And how much oil to go to Semporna to sell them? Kami rugi minyak , we are wasting oil. Also, you saw the holes in the net? I think there is a rat living in the hold.’

Most of our fishing trips ended this way, with Sarani complaining about the price of fish and the cost of diesel. The dwindling of the local fish stock was threatening their survival, and it was not just under attack from the fish-bombers. Sarani told me that they used to catch lobsters in their nets, but the ‘hookah’ fishermen had taken most of them. A weighted diver equipped only with the sort of goggles Sarani used and a nose clip goes down to the bottom breathing from a free-flowing air hose to collect them. I had read reports that they often stay at depths of 60–100 feet for as long as two hours and surface without decompression stops. The bends are a commonplace, known as bola-bola , ‘bubbles’. The method can also be used to catch desirable species of fish; the diver stuns them by releasing a cyanide poison into the water. They are sold to the ‘fish farms’ that lie in the channel between Semporna and Bum Bum. Often the ‘fish farm’ owns the boat and the compresser. They are not so much farms as way-stations. No breeding goes on. The fish are kept in pens until the cyanide has been purged from their system and then they are sent live to the Hong Kong markets.

Читать дальше