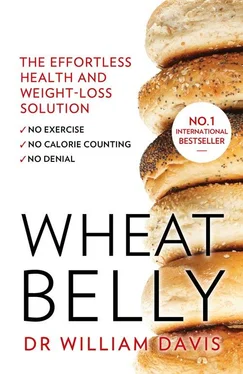

Even in the few decades since our American grandmothers survived Prohibition and danced the Big Apple, wheat has undergone countless transformations. As the science of genetics has progressed over the past fifty years, permitting human intervention at a much more rapid rate than nature’s slow, year-by-year breeding influence, the pace of change has increased exponentially. The genetic backbone of your high-tech poppy-seed muffin has achieved its current condition by a process of evolutionary acceleration that makes us look like Homo habilis trapped somewhere in the early Pleistocene.

FROM NATUFIAN PORRIDGE TO DOUGHNUT HOLES

‘Give us this day our daily bread.’

It’s in the Bible. In Deuteronomy, Moses describes the Promised Land as ‘a land of wheat and barley and vineyards’. Bread is central to religious ritual. Jews celebrate Passover with unleavened matzo to commemorate the flight of the Israelites from Egypt. Christians consume wafers representing the body of Christ. Muslims regard unleavened naan as sacred, insisting it be stored upright and never thrown away in public. In the Bible, bread is a metaphor for bountiful harvest, a time of plenty, freedom from starvation, even a source of salvation.

Don’t we break bread with friends and family? Isn’t something new and wonderful ‘the best thing since sliced bread’? ‘Taking the bread out of someone’s mouth’ is to deprive that person of a fundamental necessity. Bread is a nearly universal diet staple: chapati in India, tsoureki in Greece, pitta in the Middle East, aebleskiver in Denmark, naan bya for breakfast in Burma, glazed doughnuts any old time in the United States.

The notion that a foodstuff so fundamental, so deeply ingrained in the human experience, can be bad for us is, well, unsettling and counter to long-held cultural views of wheat and bread. But today’s bread bears little resemblance to the loaves that emerged from our forebears’ ovens. Just as a modern Napa Cabernet Sauvignon is a far cry from the crude ferment of fourth-century BC Georgian winemakers who buried wine urns in underground mounds, so has wheat changed. Bread and other foods made of wheat have sustained humans for centuries, but the wheat of our ancestors is not the same as modern commercial wheat that reaches your breakfast, lunch and dinner table. From the original strains of wild grass harvested by early humans, wheat has exploded to more than 25,000 varieties, virtually all of them the result of human intervention.

In the waning days of the Pleistocene, around 8500 BC, millennia before any Christian, Jew or Muslim walked the earth, before the Egyptian, Greek and Roman empires, the Natufians led a semi-nomadic life roaming the Fertile Crescent (now Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Israel and Iraq), supplementing their hunting and gathering by harvesting indigenous plants. They harvested the ancestor of modern wheat, einkorn, from fields that flourished wildly in open plains. Meals of gazelle, boar, fowl and ibex were rounded out with dishes of wild-growing grain and fruit. Relics like those excavated at the Tell Abu Hureyra settlement in what is now central Syria suggest skilled use of tools such as sickles and mortars to harvest and grind grains, as well as storage pits for stockpiling harvested food. Remains of harvested wheat have been found at archaeological digs in Tell Aswad, Jericho, Nahal Hemar, Navali Cori and other locales. Wheat was ground by hand, then eaten as porridge. The modern concept of bread leavened by yeast would not come along for several thousand years.

Natufians harvested wild einkorn wheat and may have purposefully stored seeds to sow in areas of their own choosing the next season. Einkorn wheat eventually became an essential component of the Natufian diet, reducing the need for hunting and gathering. The shift from harvesting wild grain to cultivating it was a fundamental change that shaped their subsequent migratory behaviour, as well as the development of tools, language and culture. It marked the beginning of agriculture, a lifestyle that required long-term commitment to more or less permanent settlement, a turning point in the course of human civilisation. Growing grains and other foods yielded a surplus of food that allowed for occupational specialisation, government and all the elaborate trappings of culture (while, in contrast, the absence of agriculture arrested cultural development at something resembling Neolithic life).

Over most of the ten thousand years that wheat has occupied a prominent place in the caves, huts and adobes and on the tables of humans, what started out as harvested einkorn, then emmer, followed by cultivated Triticum aestivum , changed gradually and only in small fits and starts. The wheat of the seventeenth century was the wheat of the eighteenth century, which in turn was much the same as the wheat of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century. Riding your oxcart through the countryside during any of these centuries, you’d see fields of four-foot tall ‘amber waves of grain’ swaying in the breeze. Crude human wheat breeding efforts yielded hit-and-miss, year-over-year incremental modifications, some successful, most not, and even a discerning eye would be hard pressed to tell the difference between the wheat of early twentieth-century farming from its many centuries of predecessors.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as in many preceding centuries, wheat changed little. The Pillsbury’s Best XXXX flour my grandmother used to make her famous sour cream muffins in 1940 was little different from the flour of her great-grandmother sixty years earlier or, for that matter, from that of a relative two centuries before that. Grinding of wheat had become more mechanised in the twentieth century, yielding finer flour on a larger scale, but the basic composition of the flour remained much the same.

That all ended in the latter part of the twentieth century, when an upheaval in hybridisation methods transformed this grain. What now passes for wheat has changed, not through the forces of drought or disease or a Darwinian scramble for survival, but through human intervention. As a result, wheat has undergone a more drastic transformation than Joan Rivers, stretched, sewed, cut, and stitched back together to yield something entirely unique, nearly unrecognisable when compared to the original and yet still called by the same name: wheat.

Modern commercial wheat production has been intent on delivering features such as increased yield, decreased production costs and large-scale production of a consistent commodity. All the while, virtually no questions have been asked about whether these features are compatible with human health. I submit that, somewhere along the way during wheat’s history, perhaps five thousand years ago but more likely fifty years ago, wheat changed.

The result: a loaf of bread, biscuit, or pancake of today is different than its counterpart of a thousand years ago, different even from what our grandmothers made. They might look the same, even taste much the same, but there are biochemical differences. Small changes in wheat protein structure can spell the difference between a devastating immune response to wheat protein versus no immune response at all.

WHEAT BEFORE GENETICISTS GOT HOLD OF IT

Wheat is uniquely adaptable to environmental conditions, growing in Jericho, 850 feet below sea level, to Himalayan mountainous regions 10,000 feet above sea level. Its latitudinal range is also wide, ranging from as far north as Norway, 65° north latitude, to Argentina, 45° south latitude. Wheat occupies sixty million acres of farmland in the United States, an area equal to the state of Ohio. Worldwide, wheat is grown on an area ten times that figure, or twice the total acreage of Western Europe.

Читать дальше