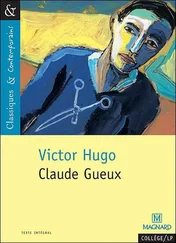

This constituted the terror of the poor creature whom the reader has probably not forgotten,—little Cosette. It will be remembered that Cosette was useful to the Thénardiers in two ways: they made the mother pay them, and they made the child serve them. So when the mother ceased to pay altogether, the reason for which we have read in preceding chapters, the Thénardiers kept Cosette. She took the place of a servant in their house. In this capacity she it was who ran to fetch water when it was required. So the child, who was greatly terrified at the idea of going to the spring at night, took great care that water should never be lacking in the house.

Christmas of the year 1823 was particularly brilliant at Montfermeil. The beginning of the winter had been mild; there had been neither snow nor frost up to that time. Some mountebanks from Paris had obtained permission of the mayor to erect their booths in the principal street of the village, and a band of itinerant merchants, under protection of the same tolerance, had constructed their stalls on the Church Square, and even extended them into Boulanger Alley, where, as the reader will perhaps remember, the Thénardiers’ hostelry was situated. These people filled the inns and drinking-shops, and communicated to that tranquil little district a noisy and joyous life. In order to play the part of a faithful historian, we ought even to add that, among the curiosities displayed in the square, there was a menagerie, in which frightful clowns, clad in rags and coming no one knew whence, exhibited to the peasants of Montfermeil in 1823 one of those horrible Brazilian vultures, such as our Royal Museum did not possess until 1845, and which have a tricolored cockade for an eye. I believe that naturalists call this bird Caracara Polyborus; it belongs to the order of the Apicides, and to the family of the vultures. Some good old Bonapartist soldiers, who had retired to the village, went to see this creature with great devotion. The mountebanks gave out that the tricolored cockade was a unique phenomenon made by God expressly for their menagerie.

On Christmas eve itself, a number of men, carters, and peddlers, were seated at table, drinking and smoking around four or five candles in the public room of Thénardier’s hostelry. This room resembled all drinking-shop rooms,—tables, pewter jugs, bottles, drinkers, smokers; but little light and a great deal of noise. The date of the year 1823 was indicated, nevertheless, by two objects which were then fashionable in the bourgeois class: to wit, a kaleidoscope and a lamp of ribbed tin. The female Thénardier was attending to the supper, which was roasting in front of a clear fire; her husband was drinking with his customers and talking politics.

Besides political conversations which had for their principal subjects the Spanish war and M. le Duc d’Angoulême, strictly local parentheses, like the following, were audible amid the uproar:—

“About Nanterre and Suresnes the vines have flourished greatly. When ten pieces were reckoned on there have been twelve. They have yielded a great deal of juice under the press.” “But the grapes cannot be ripe?” “In those parts the grapes should not be ripe; the wine turns oily as soon as spring comes.” “Then it is very thin wine?” “There are wines poorer even than these. The grapes must be gathered while green.” Etc.

Or a miller would call out:—

“Are we responsible for what is in the sacks? We find in them a quantity of small seed which we cannot sift out, and which we are obliged to send through the mill-stones; there are tares, fennel, vetches, hempseed, fox-tail, and a host of other weeds, not to mention pebbles, which abound in certain wheat, especially in Breton wheat. I am not fond of grinding Breton wheat, any more than long-sawyers like to saw beams with nails in them. You can judge of the bad dust that makes in grinding. And then people complain of the flour. They are in the wrong. The flour is no fault of ours.”

In a space between two windows a mower, who was seated at table with a landed proprietor who was fixing on a price for some meadow work to be performed in the spring, was saying:—

“It does no harm to have the grass wet. It cuts better. Dew is a good thing, sir. It makes no difference with that grass. Your grass is young and very hard to cut still. It’s terribly tender. It yields before the iron.” Etc.

Cosette was in her usual place, seated on the cross-bar of the kitchen table near the chimney. She was in rags; her bare feet were thrust into wooden shoes, and by the firelight she was engaged in knitting woollen stockings destined for the young Thénardiers. A very young kitten was playing about among the chairs. Laughter and chatter were audible in the adjoining room, from two fresh children’s voices: it was Éponine and Azelma.

In the chimney-corner a cat-o’-nine-tails was hanging on a nail.

At intervals the cry of a very young child, which was somewhere in the house, rang through the noise of the dram-shop. It was a little boy who had been born to the Thénardiers during one of the preceding winters,—“she did not know why,” she said, “the result of the cold,”—and who was a little more than three years old. The mother had nursed him, but she did not love him. When the persistent clamor of the brat became too annoying, “Your son is squalling,” Thénardier would say; “do go and see what he wants.” “Bah!” the mother would reply, “he bothers me.” And the neglected child continued to shriek in the dark.

Chapter II

Two Complete Portraits

––––––––

SO FAR IN THIS BOOK the Thénardiers have been viewed only in profile; the moment has arrived for making the circuit of this couple, and considering it under all its aspects.

Thénardier had just passed his fiftieth birthday; Madame Thénardier was approaching her forties, which is equivalent to fifty in a woman; so that there existed a balance of age between husband and wife.

Our readers have possibly preserved some recollection of this Thénardier woman, ever since her first appearance,—tall, blond, red, fat, angular, square, enormous, and agile; she belonged, as we have said, to the race of those colossal wild women, who contort themselves at fairs with paving-stones hanging from their hair. She did everything about the house,—made the beds, did the washing, the cooking, and everything else. Cosette was her only servant; a mouse in the service of an elephant. Everything trembled at the sound of her voice,—window panes, furniture, and people. Her big face, dotted with red blotches, presented the appearance of a skimmer. She had a beard. She was an ideal market-porter dressed in woman’s clothes. She swore splendidly; she boasted of being able to crack a nut with one blow of her fist. Except for the romances which she had read, and which made the affected lady peep through the ogress at times, in a very queer way, the idea would never have occurred to any one to say of her, “That is a woman.” This Thénardier female was like the product of a wench engrafted on a fishwife. When one heard her speak, one said, “That is a gendarme”; when one saw her drink, one said, “That is a carter”; when one saw her handle Cosette, one said, “That is the hangman.” One of her teeth projected when her face was in repose.

Thénardier was a small, thin, pale, angular, bony, feeble man, who had a sickly air and who was wonderfully healthy. His cunning began here; he smiled habitually, by way of precaution, and was almost polite to everybody, even to the beggar to whom he refused half a farthing. He had the glance of a pole-cat and the bearing of a man of letters. He greatly resembled the portraits of the Abbé Delille. His coquetry consisted in drinking with the carters. No one had ever succeeded in rendering him drunk. He smoked a big pipe. He wore a blouse, and under his blouse an old black coat. He made pretensions to literature and to materialism. There were certain names which he often pronounced to support whatever things he might be saying,—Voltaire, Raynal, Parny, and, singularly enough, Saint Augustine. He declared that he had “a system.” In addition, he was a great swindler. A filousophe [philosophe], a scientific thief. The species does exist. It will be remembered that he pretended to have served in the army; he was in the habit of relating with exuberance, how, being a sergeant in the 6th or the 9th light something or other, at Waterloo, he had alone, and in the presence of a squadron of death-dealing hussars, covered with his body and saved from death, in the midst of the grape-shot, “a general, who had been dangerously wounded.” Thence arose for his wall the flaring sign, and for his inn the name which it bore in the neighborhood, of “the cabaret of the Sergeant of Waterloo.” He was a liberal, a classic, and a Bonapartist. He had subscribed for the Champ d’Asile. It was said in the village that he had studied for the priesthood.

Читать дальше