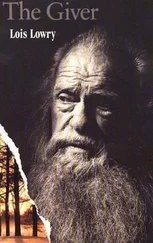

The Giver – an old man who is feeling the burden of the memories he must keep and the pain he must carry alone. He is tired and sad.

Jonas’ family (mother, father, his sister Lily and baby Gabriel)

Further characters: Fiona and Asher (childhood friends of Jonas), Rosemary and the Chief Elder.

Themes:

The major themes we will look at in this study guide are control , pain , Sameness and diversity, memory(history and the past) and choice. Another major theme is human connections.

Style and Language:

This is a particularly important aspect of the novel, because one of the major methods by the dystopian society in the novel to control the people is “precision of language”. The horrific secrets are hidden by euphemisms: truth and the very nature of reality is hidden or manipulated by the use of specific language.

Interpretation:

The book can be interpreted in the context of at least three genres to which it belongs – Young Adult fiction, science fiction and dystopian fiction.

There has been a major film adaptation (in 2014), which allows us a different perspective on the story and its themes.

Other ideas about interpretations of The Giver

| 2. |

Lois Lowry: Life & Works |

Lois Lowry (*1937)

© 2016 Larry D. Moore[1]

| YEAR |

PLACE |

EVENT |

AGE |

| 1937 |

Honolulu/Hawaii (USA) |

20th of March: Lois (originally Cena) Lowry is born. She is the middle child of three. Her parents are Norwegian (father) and German, English, Scots-Irish (mother). |

|

| 1939 |

Brooklyn/New York (USA) |

Her father was a dentist in the US military and like many military families, they had to move often. This was the first relocation of Lois’ life. |

2 |

| 1942 |

Carlisle/Pennsylvania (USA) |

When her father had to serve on a hospital ship in the Pacific during World War 2, the rest of the family moved back to Lois’ mother’s hometown. |

5 |

| 1948– 1950 |

Tokyo (Japan) |

Her father was stationed in Japan and the family lived on a military base for a couple of years. Lois returned to the US to attend high school. |

11–13 |

| 1954– 1956 |

Providence/Rhode Island (USA) |

Lois studied at Pembroke College for two years until she married Donald Lowry. |

17–19 |

| 1956– 1972 |

Many locations |

Donald Lowry was also in the US military and the young family (Lois was to have 4 children during the early years of their marriage) moved often during this period, as he was stationed at different military bases around the country. They eventually settled after his retirement in Portland, Maine, where Lois finished her studies and graduated from the University of Southern Maine with a degree in English Literature. |

19–35 |

| 1963 |

Washington D.C. (USA) |

Lois’ older sister Helen dies of cancer, aged 28. This event inspires her first novel. |

26 |

| 1977 |

Maine (USA) |

Lowry is commissioned by the publisher Houghton Mifflin to write a book, which becomes her first published novel, A Summer to Die . Lois and Donald divorce. |

40 |

| 1979 |

Boston/Massachusetts (USA) |

After her divorce Lois moved to live and work in Boston. |

42 |

| 1990 |

Chicago (USA) |

Newbery Award for the novel Number the Stars . |

53 |

| 1993 |

Boston (USA) |

The Giver is published. |

56 |

| 1994 |

Chicago (USA) |

Second Newbery Award for The Giver. |

57 |

| 1995 |

Spangdahlem Air Base/ Rheinland-Pfalz (Germany) |

Her second son Grey, a pilot in the US Air Force, is killed when his plane crashes. Lois describes this event as the most difficult day of her life. |

58 |

| 2014 |

New York |

Film adaptation of The Giver. |

77 |

| 2018 |

Massachusetts and Maine (USA) |

Lowry currently lives in the US states of Massachusetts and Maine. |

81 |

| 2.2 |

Contemporary Background |

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

Lois Lowry wrote The Giver in the early 1990s. She had already been a professional writer for nearly 20 years by that time. It is maybe surprising for a writer to have their most famous and critically acclaimed work come in the middle of their careers, rather than in an explosion of energy at the beginning or as a crowning achievement towards the end.

The 1990s and the “end of history”

The early 1990s were a strange time in history. Following the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the reunification of Germany, many people thought that the world had reached what was called “the end of history”. This was a philosophical idea made popular by Francis Fukuyama 1992 in his bestselling book The End of History and the Last Man . Fukuyama’s idea, very basically, is that Western-style liberal democracy had “won” the competition between different political and social systems, and that from this point on all people and countries would be increasingly on the same path to shared enlightenment, progress, peace and security. Formerly competing ideologies like Communism and extreme nationalism would become weaker and would vanish into history.

But this view of the world turned out to be premature and optimistic. Within just a couple of years it was clear that rampant nationalism was still widespread, China’s capitalist-Communist hybrid system was becoming an increasing concern for Western nations, and globalised terrorism had a historic comeback in the public eye with al Qaeda’s 9/11 attacks. By the turn of the millennium Fukuyama’s theories seemed quaint and lost to history.

What is true of the period, however, is that with the end of the Cold War a universal sense of dread and doom was suddenly gone – the world no longer seemed to be a potential battlefield between nuclear-armed superpowers representing capitalism and Communism. This sense of dread and monolithic antagonism had fuelled a lot of pop culture, from British pop band Frankie Goes to Hollywood ’s song Two Tribes (1984) to the spy novels of John le Carré and successful, but deeply chauvinistic America = good / Russia = badfilms like Red Dawn (1984) and Rocky IV (1985). With the collapse of the Russian “evil empire” (a term used by US President Ronald Reagan in 1983 to describe the Soviet Union[2]) and the apparent “end of history”, pop culture changed as well.

It became much less political: the eras of Margaret Thatcher, Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1979–1990, and Ronald Reagan, US president from 1981–1989, were both very conservative and pro-capitalism. Their administrations were both extremely polarisingin their respective countries, and triggered energetic subcultural and alternative culture movements, including punk, US hardcore punk, the social-realist cinema of filmmakers like Mike Leigh and Ken Loach, and a general willingness and need for art and pop culture to engage actively and confrontationally with politics. With the end of the era of the Cold War and Cold Warriors like Thatcher and Reagan, this political energy vanished from pop culture, and an era of curiosity, fusion, and non-political hedonism began.

Читать дальше